Why A Scanner Darkly is Keanu Reeves’ most underrated movie

With Keanu Reeves back on the big screen in Good Fortune, it’s the perfect time to revisit his most under-appreciated film: a mind-bending, visually unique sci-fi.

When asked to name a good Keanu Reeves movie, most people will reach for classics—like The Matrix, Speed, Point Break, John Wick or Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. They almost certainly won’t think of a 2006 adaptation of a Philip K. Dick sci-fi novel that’s a bizarre combination of animation and live-action, suspended in an uncanny space between real and artificial.

Which is a shame, because I think A Scanner Darkly is one of Reeves’s best films: an undercover-cop drama that digs into a paradox that’s surely confronted more than a few real-life narcs. To pose as an addict, Reeves’s character, Bob Arctor, has to become a user. And by becoming a user, he becomes…

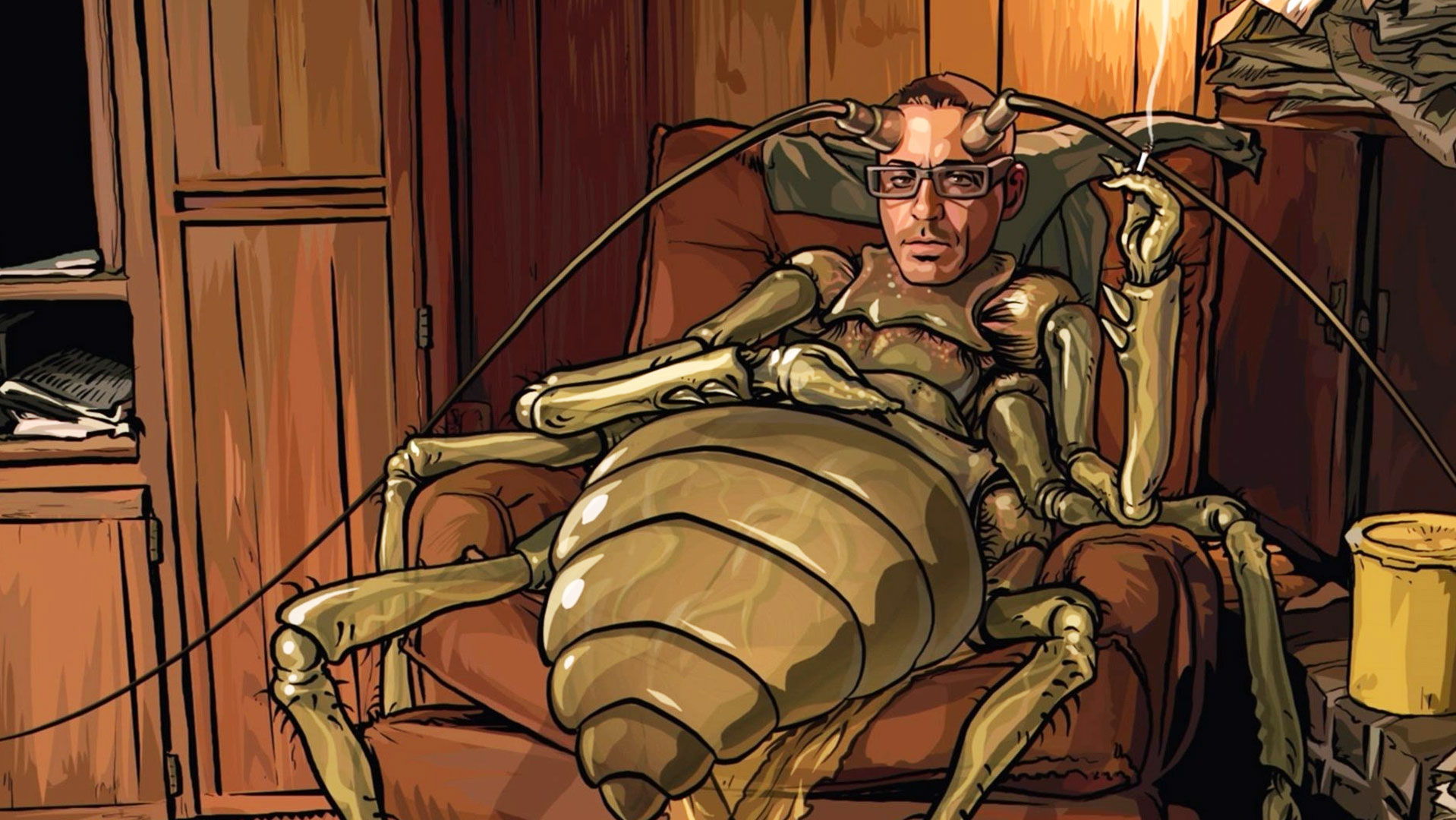

Yes, yes, an addict. Just when the case is heating up, and Arctor most needs his wits about him, he starts to lose his grip on reality—impaired by the long-term effects of a highly addictive hallucinogenic drug called Substance D. The film itself has lost that grip too, at least visually: director Richard Linklater created it using a process called digital rotoscoping, where footage of real actors gets painted over with animation, giving everything a surreal hand-drawn shimmer—part real, part hallucination. This lets Linklater bend the frame any way he wants, adding all sorts of kooky visual flourishes, making it feel like the film itself is tripping.

This approach is well suited to a story about drug users, pulling us inside their mooshy addled brains and nudging us away from reality without cutting the cord completely. Linklater deployed it once before, in Waking Life—a collection of heady conversations about existence and free will, based in dream-like environments—and once again in Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood. In that wonderful Netflix film, he uses it to illustrate a child’s blend of memory and make-believe: the protagonist’s conviction that he was secretly recruited by NASA to save the moon landing.

You really feel the in-between space that digital rotoscoping occupies—between real and unreal—when observing famous actors. In A Scanner Darkly, these include, in addition to Reeves, Winona Ryder as Donna, Woody Harrelson as Ernie, and Robert Downey Jr. as James—all twitchy druggy types slumming around in Arctor’s suburban home. Things heat when one of the plot’s excellent twists (there’s a few of them) kicks in. Arctor’s superiors task him with monitoring and investigating himself; he’s even told to find evidence and “make it stick.” He wants to follow orders, of course, but he also doesn’t want to inadvertently put himself in the slammer.

This spectacular conflict of interest arises because nobody in the force knows the identity of the undercover cops. During in-person meetings, their anonymity is maintained through use of a “scramble suit”—a shapeshifting outfit that constantly changes its wearer’s appearance, including their clothes and facial features. It’s fascinating to look at: a kind of human kaleidoscope in motion. The film is set in a near-future where such technologies exist, and where approximately 20% of the American population is hooked on Substance D.

A Scanner Darkly doesn’t shy from showing the damage caused by a substance that leads to “slow death, from the head down.” But at its core there’s a powerful message about the war on drugs—including its abject futility and how it turns decent, average people into criminals. And, more ambitiously and polemically, it argues that the war on drugs transforms citizens into exploitable commodities to fuel the capitalist system. This hits with force during the film’s final moments, which deploy a massive surprise ending I won’t spoil here.

There’s a lot to appreciate, including a unusual blend of comedy—the characters engaged in various funny conversations, part Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, part mumblecore. Reeves is very good too, delivering a powerful anchoring performance that feels well-balanced and even restrained. This film is far from a footnote in Reeves’ career: it’s a quietly dazzling, visually inventive experience that rewards a taste for the strange.