7 reasons why you should love Suspiria, old and new

The new Suspiria is less a remake of the original than a love letter to it.

The new Suspiria is less a remake of the original than a love letter to it. Critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, who literally wrote the book on Suspiria, provides seven reasons to love both versions.

Many will have already decided how they feel about Luca Guadagnino’s reimagining of Dario Argento’s cult 1977 Eurohorror classic Suspiria before even seeing it. For some old-school horror fans, it’s straightforward sacrilege; the magic that rendered Suspiria one of the most beloved horror films ever made simply cannot be rekindled.

For many ‘Guadaginittes’ – drawn by the lure of 2015’s A Bigger Splash and 2017’s Call Me By Your Name (2017) – ‘horror’ itself might be a barely tolerable proposition, Guadagnino’s name rather than the subject matter the reason for their interest.

In 2015, I wrote a whole book about Argento’s Suspiria, but before seeing Guadagnino’s Suspiria I wisely put this battle-of-the-Suspiria’s attitude to rest. 2018’s Suspiria is less a remake than a love letter to the original; both straddle horror and art cinema, but in different ways. Rather than recycling Argento’s film, the original ignited Guadagnino’s own delirious vision of the same name.

Here’s seven ways we can appreciate the two films that – while intersecting – are still vibrant and visionary masterworks in their own right.

Setting Up Suspiria

Both films involve an American dancer in Germany who becomes involved with a coven of witches. In 1977, Suzy (Jessica Harper) is a ballet student at the Freiburg Tanzakademie run by headmistress Madam Blanc (Joan Bennett) and its director, Helena Markos (Lela Svasta). Through her friend Sara (Stefania Casini), Suzy’s confronts the witches and reveals her inner strength.

2018’s Susie (Dakota Johnson) is another American dancer in Germany (this time Berlin) cultivating her skills in modern dance at the Markos Tanzgruppe, led by its director, Madam Blanc (Tilda Swinton). Susie too discovers with Sara’s (Mia Goth) help that witchcraft is at play here also, although her power is unveiled in a way altogether unlike that of her predecessor.

Building Suspiria

Dario Argento and actor/writer/director Daria Nicolodi met while making Argento’s 1975 giallo Deep Red, sparking a romantic relationship that resulted in the birth of their daughter Asia. It was Nicolodi who discovered in Thomas De Quincey’s Suspiria De Profundis the essay “Levana and Our Ladies of Sorrow”, the source of Suspiria’s legendary “three mothers” which provided the foundations of Argento and Nicolodi’s screenplay.

Guadagnino also worked with his primary collaborator previously. David Kajganich wrote A Bigger Splash, and while Nicolodi and Argento researched the history of witchcraft in Europe, Kajganich looked instead towards two other areas: 1970s German politics, and contemporary dance.

Choreographing Suspiria

For a film set in a ballet school, there’s a notable lack of dancing in Argento’s Suspiria: the one time Suzy tries, she immediately faints. For Argento, dance is reimagined as the spectacle of writhing, spasming bodies in a spectacular parade of elaborate murder vignettes, a literal danse macabre.

Kajganich’s research into 20th century dance icons like Pina Bausch and Mary Wigman resulted, however, in a film full of dancing. For Kajganich, dance is a kind of “spell-casting”, allowing the dynamics between Suzy and Blanc to play out as women’s power is reconfigured through their own (and each other’s) bodies.

Politicising Suspiria

Setting Suspiria in 1977 allowed Guadagnino and Kajganich to work the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group into their story, drawing parallels with the politics of the coven itself. Baader-Meinhof were closely aligned with post-War German identity as a new generation of German youth found themselves detached and disillusioned by their nation’s Nazi past, a key theme in Guadagnino’s Suspiria.

Argento’s Suspiria was released in 1977, a year after Ulrike Meinhoff died in prison in controversial circumstances that sparked the backdrop of Guadagnino’s film. Germany’s Nazi past was also of interest to Argento: the scene where the blind piano player is murdered was filmed in Munich’s Königsplatz, the location of many Third Reich rallies.

Filming Suspiria

Both Guadagnino and Argento selected cinematographers with no previous experience in horror filmmaking. Argento’s film was shot by Luciano Tovoli, who with his close relationship to neo-realism (he was cinematographer for Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1975 film The Passenger) was initially bewildered that Argento would want him for such a different kind of movie. But Tovoli embraced the experimental potential of Technicolor, using the very last of the available film stock to grant Suspiria its unique look.

Like Call Me by Your Name, Guadagnino turned to Thai cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom who also shot Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Palme D’Or-winning Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. Rejecting Tovoli’s jewel tones, Mukdeeprom’s cinematography instead recalls German auteur Rainer Werner Fassbinder (who, coincidentally, Argento would drink with alongside David Bowie while shooting Suspiria in Munich).

Referencing Suspiria

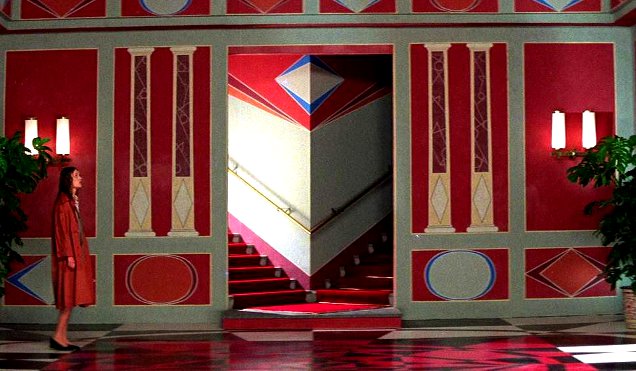

Argento’s Suspiria is unapologetically baroque and cluttered with ornate, shiny surfaces, from brightly coloured stained glass windows that his unfortunate victims will smash through, to the garish “bird with crystal plumage” ornament in its climax (a cute reference to the title of Argento’s 1971 debut film).

Guadagnino nods to these aspects without collapsing into fan-service. For example, take when Goth’s Sara finds herself in a mirrored dance studio searching for the entrance to the witches’ lair like Harper’s Suzy in the original. While the latter discovers the hidden entrance in the floral mural, Sara’s discovery lies behind the reflection of her patterned robe, recalling the wallpaper in Argento’s original.

The Heart of Suspiria

Catching Argento’s eye in Brian De Palma’s 1974 film Phantom of the Paradise, Jessica Harper had the look he wanted. Part a young Joan Bennett and part Disney’s Snow White (a key influence on his film), Harper’s Suzy was the perfect balance of innocence and experience Argento wanted.

Harper’s casting in Guadagnino’s Suspiria is therefore the only stamp of approval many Argento fans need, although here she plays an altogether different character. But she is the emotional glue that ties the film’s together across the almost four decades that separates them. Through Harper, time is crossed and beloved stories are told and reimagined, welcoming audiences old and new to tales of horror where light shines in the darkest of places.