Canterbury, cannabis, and cannibals: the making of NZIFF-selected horror The Weed Eaters

We chat to three of the four pillars behind Kiwi cannibal horror The Weed Eaters ahead of its World Premiere at NZIFF.

Making its World Premiere at Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival, homegrown horror flick The Weed Eaters marks the feature narrative debut of prominent filmmaking duo Sports Team—AKA Callum Devlin and Annabel Kean.

Capitalising on their bountiful experience making music videos for some of Aotearoa’s most prominent artists, which includes a 2020 concert film for The Beths, their strong presence as back-to-back Grand Finalists in the 48Hours Filmmaking Competition, and generally being some of the busiest content creators in the country, Devlin and Kean collaborated heavily with actor Alice May Connolly and actor/screenwriter Finnius Teppett for a film about a strain of weed that gives its tokers a taste for human flesh.

The horror of being high in the wrong circumstances comes from a genuine place, Callum reveals: “I had a bad habit of smoking too much weed before going to the movies. It was at one of the big [NZIFF screenings]—Crimes of the Future. I hadn’t looked up what it was about (intentionally) and 15 minutes into the film, after the premise was explained, I had full blown panic attack and had to leave the Civic.”

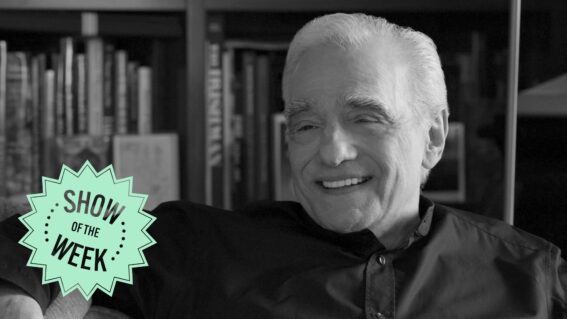

Panic attack material…

…from Crimes of the Future

That experience, alongside similar panic attacks in IMAX and Hollywood Avondale, sparked the idea for The Weed Eaters.

“I was thinking about weed as a horror element,” Callum explains. “The idea of cannibal weed came pretty quickly, and then it was that horrible feeling of… Does this film exist? Googled it. No, no one’s done this. We need to make this film immediately.”

Beyond the cannibalistic cannabis, the film also explores the difficulty of making friends in your 30s.

“That’s probably the truth that was mirrored in the film,” Finnius shares. “It’s about four friends going on a crazy adventure, and there was four of us that went down to Canterbury to start working on the movie. We were kind of living it as we were writing it.”

The group has tight ties to Canterbury, which meant free accommodation for them and everyone who could assist with the movie. “We shot at Kowai Bush,” Annabel explains. “My parents have had a chunk of land there for 15 years or so and have been spending time making huts. We knew we could accommodate everyone. We’re very lucky to have parents who were like, ‘Come stay with us for free.’ That’s the only way we could do it.”

“And my parents live in Christchurch,” Callum mentions. “On the weekends, everyone would go into town and do laundry and collapse for a couple of nights. I also love the idea of shooting places where we’re emotionally connected to. We shot it with a lot of love, like you would a family member.”

As well as being friendly on the budget, this homecoming summer production proved healing for Callum. “When we were at Kowai, my anxiety just went away. I stopped biting my fingernails [and they] grew back. I felt so calm and centred and present, surrounded by my friends. The whole thing was a dream come true. That strong feeling of… this is right, this is what we should be doing, can we please do this all the time?”

Finnius chimes in: “I’d just like to mention the production value of the Southern Alps. The landscape down there is incredible. And we shot nice and wide. We were really feeding off the vibes, the scenery, and the emotional history.”

Production operated on a $19,000 budget—a “deceptively low” cost according to the NZIFF notes —raised mostly through Sports Team’s Boosted campaign with the help of short film screening nights and t-shirt sales. That money mostly covered food with the crew making the most of their own gear, borrowing stuff, and calling in favours from generous people and the local tight-knit community who were willing to help. Causeway Films did plenty of heavy lifting with postproduction.

How did they know this microbudget plan would work? Annabel lays out the thinking: “Every time we made a music video, we’d have enough footage for a short film. One of our proof of concepts was… we shot three music videos for Vera Allen, with Samuel Austin as DOP, in three days with a story that goes through them.”

Callum crunched the numbers: “We just had to make 60 music videos and we could pull the film off. Story-wise, we were leaning very heavily on our esteemed colleague Finn.”

“It was going to be a working holiday,” Finnius adds. “We had the summer free, and we had food and accommodation sussed.”

That also meant a compressed writing period for Finn. “I didn’t have my ideal amount of time to write. We only had half the script done when we started shooting, and I was acting in it as well, so I had to get my angles down and then run up to my little hut and write the rest of the movie.”

Finnius had the roughest workload and the least amount of sleep, Annabel reckons, though everyone felt the strain at some point. “The hardest thing was [maintaining] energy. Trying to not fall asleep. We’d be in this hot, corrugated iron barn with mattresses and stuff because that’s where the characters were sleeping. And when I didn’t have anything to do, I would just lie down and sleep.”

Callum adds: “Samuel had double duties—actor and director of photography—which is a challenge that convinced him to do the project, I’ll have you know. But he’ll be the first to say, ‘Never again.’ And then Ollie, my brother and the sound person on the film, was promoted to assistant director on day two.”

The scrappy DIY nature of the independent production sounded like a typical 48Hours weekend, albeit over an entire summer period. “That was a big reference,” Callum states. “We actually did 48Hours after the film shoot as well, a film called Beware the Kraken. It had been months since the shoot, and I was panicking, but then I got handed some beautiful script pages from Finn and I was like, ‘Oh, I can do this. No problem.’”

There’s no graceful way to explain this next part: I was privy to some early information regarding a scene involving a stop-motion animated worm with a humongous bosom voiced by comedian and Spelling Bee mogul Guy Montgomery. I later learned the scene isn’t in the final film. I ask why.

Callum confesses: “It was a long prank on Guy Montgomery.”

Annabel objects: “No! Don’t say that. It’s not true. I’d done some of the animation, built different sets and models, but after a round of feedback from EPs, they pointed out the scene truly wasn’t necessary. If anything, it slowed down this momentum right in the middle of the film. We all went, ‘…that’s true.’ And had to kill Double D the worm.”

“The ultimate darling to kill,” Finnius laments.

“No one had a problem with the content,” Callum reassures. “Everyone was two thumbs up for big breasted worm-shaped Jiminy Cricket appearing in the middle of the movie, but for story reasons, it had to go. But the film is better for it.”

THIS INTERVIEW HAS BEEN EDITED FOR BREVITY AND CLARITY