Cruise ship rescue drama Unwanted does more than trade in rote thriller tropes

Unwanted is both a gripping drama, and an important opportunity to confront some unpleasant truths.

A cruise ship picks up survivors of a shipwreck, desperate not to be returned to Libya, in Unwanted – streaming on Neon. While it builds towards a thriller, the show is more interested in exploring and conveying the human dimension of the migrant experience, writes Steve Newall.

Cruise ships have long provided the setting for onscreen wish fulfilment and entertainment—from The Love Boat’s guest star-propelled romances to whatever you’d like to say about Speed 2: Cruise Control. But new series Unwanted, set aboard a 5000-passenger cruise ship, is more interested in confronting uncomfortable realities, leaning into the stuff of headlines rather than indulging in fantasies.

It’s not the giant cruise ship Orizzonte that appears first in the series, though. Unwanted opens on a beach, a frightened-looking group huddled in the shadows until the sound of an approaching boat is heard. They run en masse into the water—except one woman, who’s on the waterline, reluctant to go further. “You’ll die if you stay here,” she’s told. “Tomorrow we’ll be in Italy”.

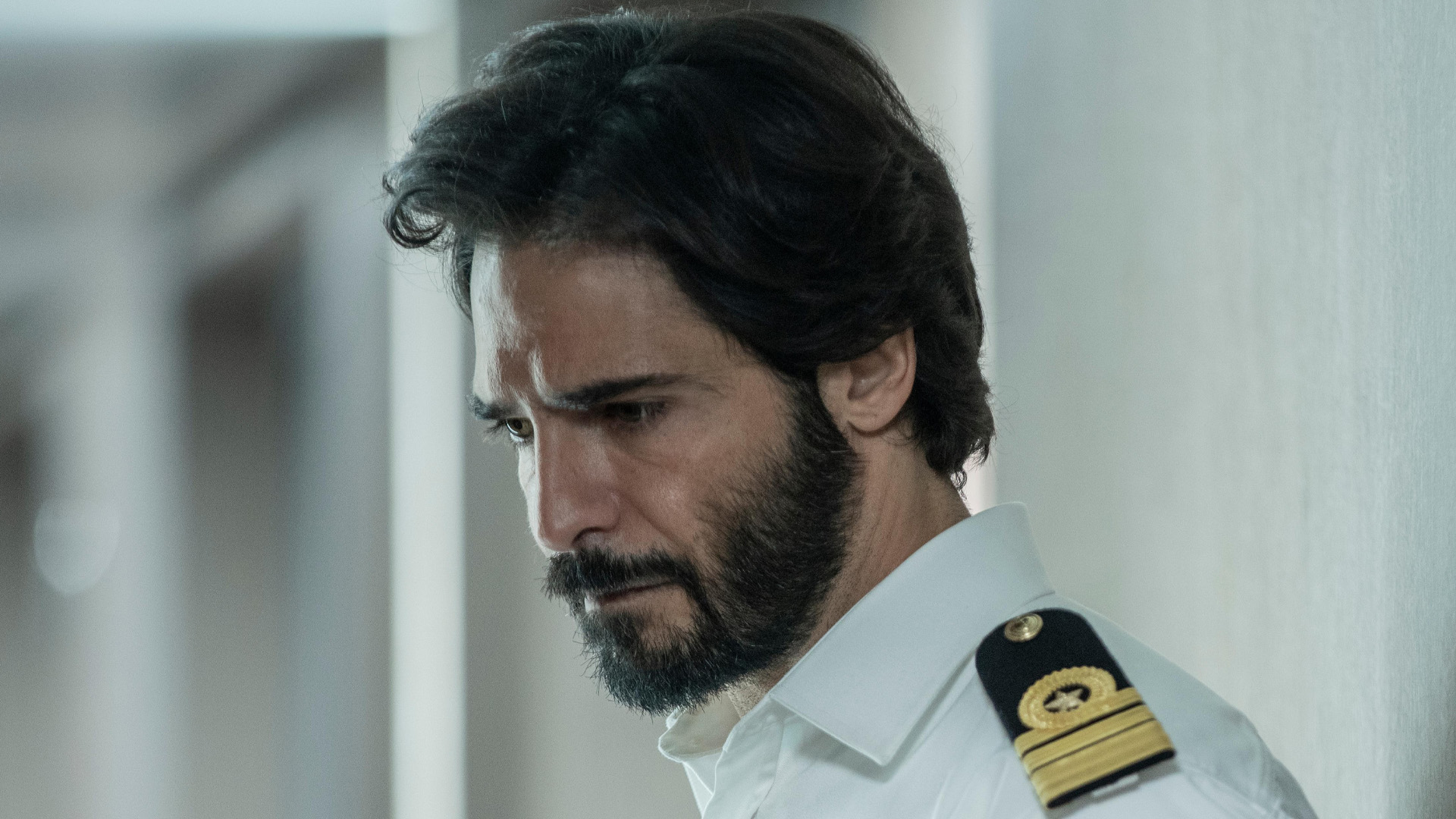

Italians are among the next characters we meet—except they’re partying on the top deck of the Orizzonte, an enormous, gaudy vessel with more than a touch of tackily wealthy Eurotrash to it. It’s night-time, two days after the opening scene on the beach, but as the passengers dance the night away far above the Mediterranean ocean, the ship’s captain spots a glow on the water—a ship’s on fire, and he quickly scrambles rescue boats to pick up survivors.

Those that make it to the Orizzonte (many do not) turn out to be people fleeing for their lives from Libya. As they’re examined by the ship’s doctor, they’re found to bear the scars of torture—shown later in flashbacks as a method of extracting money from relatives over the phone by way of a blowtorch and super-heated steel rods applied to torture victims.

Unwanted is based on the experiences of Italian investigative journalist Fabrizio Gatti. His book Bilal: Travelling, Working and Dying Illegally—named after the identity Gatti assumed—chronicled his time posing as a Kurdish asylum seeker. As Bilal, Gatti travelled refugee routes across the Sahara for four years, until he himself was caught adrift in the Mediterranean and detained by Italian immigration authorities.

While its not a direct adaptation, the characters fleeing Libya in Unwanted feel like they’ve been influenced greatly by Gatti’s real-life experiences, and those of the migrants he encountered. They’re real people placed in impossible positions, and while it may have meant they did not drown, being aboard the Orizzonte turns out to be another of those.

No cruise ship wants to disturb its wealthy, comfortable passengers. The rescued are sequestered in a wing devoid of other guests, and even if their new environs may impress initially, they’re essentially on house arrest. Worse yet, they’re an object of fascination, even entertainment, to some of the passengers. Othered in one way or another by the uniformly white paying customers, the Black refugees are encouraged at one point to share something about themselves with others aboard.

“Ladies and gentlemen, here they come—our superheroes from Africa,” says one of the ship’s entertainment staff, a grossly tone deaf welcome to the theatre stage. As uncomfortable as that is for us to watch, the audience that has gathered is unprepared for the cold dose of reality that comes their way—harrowing accounts of abuse written matter-of-factly, read by their fellow passengers to a thinning-out theatre crowd, unwilling to acknowledge the reality in front of them.

Sure, some of the ship’s passengers want to “help”—but do they really just want to impress? Are they attracted to these exotic arrivals? Or are they assuaging their guilt about privilege, about wealth? Whatever their intentions, the stakes for the rescued people are higher than anyone on board could really conceive of—reaching the Orizzonte has kept them alive, but that doesn’t mean they are safe.

The cruise ship isn’t heading straight to Italy, as the would-be refugees had hoped. And, as the captain discovers, the cruise ship company wants nothing to do with assisting any migrants. The cruise is ordered to continue (the passengers don’t seem to mind any) and the asylum-seekers to be disembarked in Tunis. The implication of this being a return to Libya and to certain suffering and death…

Unwanted spends four of its eight episodes building up this pressure until something has to give, plenty of time to flesh out its ensemble cast on both sides of the privilege divide. By the time some of the asylum seekers take matters into their own hands, seeking control of the ship, the show has patiently established itself, and lent verisimilitude to proceedings with a mix of flashbacks to the horrors of Libya and staged interviews from the aftermath of events aboard the ship.

It’s clear that tragedy lies ahead, but in taking time to set up the hostage drama elements of the story, Unwanted does more than trade in rote thriller tropes. It’s a show more interested in exploring and conveying the human dimension of the migrant experience, happening every day on a scale that’s hard for us to comprehend, but requires us to. The show’s title may refer to the men, women and children rescued from the ocean, but it could just as easily describe the conclusions we draw, or emotions and guilt we feel, when watching it. Unwanted is both a gripping drama, and an important opportunity to confront some unpleasant truths in an increasingly nationalistic, fascist, and dehumanised world.