From book to stage and screen: the many lives of Let the Right One In

John Ajvide Lindqvist’s chilling vampire novel has been adapted a bunch of times. Somehow, it’s always great.

One of horror’s most immortal, iconic monsters enjoys fresh blood with each adaptation of Let The Right One In, most recently in the new TV series. Travis Johnson walks us through the differences and key themes of each retelling.

Let the Right One In: Season 1

Swedish author John Ajvide Lindqvist’s chilling vampire novel Let the Right One In has proved a perennial favourite for horror fans since it was first published in 2004. First there was the acclaimed Swedish-language 2008 film directed by Tomas Alfredson which was quickly followed by an American remake, retitled Let Me In, in 2010.

It was later adapted twice for the stage: once in Swedish by Lindqvist in 2011, and once in English by British playwright Jack Thorne. Now we have a television series starring Demián Bichir streaming on Paramount+. There’s even a four-part comic book prequel, but Lindqvist has disavowed it (he accidentally signed away the rights at some point).

That’s a lot of takes on the same material and, flying in the face of all probability, they’re all pretty good. But they all take different approaches to the same basic material, and those differences are interesting. Spoilers obviously follow.

The novel: Let the Right One In

In 1981 Stockholm, 12-year-old Oskar is an alienated and potentially dangerous teen. Bullied at school, he collects newspaper clippings of murders and fantasises about violent revenge. His world changes when Eli, seemingly a girl his own age, moves into his apartment complex with her guardian, Hakan. Eli is, of course, a vampire, and the novel traces the relationship that develops between the two.

Lindqvist’s novel is darker and more overtly supernatural than any of the adaptations—Eli can grow claws and wings, for one thing. It also has the luxury of being able to expand on background elements. The most obvious is Eli’s origin; we learn that Eli was born a boy, Elias, but castrated when turned into a vampire centuries ago.

The relationship between Eli and Hakan is pedophilic in nature; Hakan was fired from his teaching job for possessing child pornography. For those familiar with the more oblique film versions, reading the book can be a real eye opener; what the movies allude to, Lindqvist makes plain.

The movie: Let the Right One In (2008)

Alfredson’s film, a chilly masterpiece, necessarily condenses the novel, eliding away some of the complexities and side-plots but managing to imply a lot. As Eli, Swedish-Iranian actor Lina Leandersson is androgynous enough to indicate her gender may not be what it seems, and she explicitly tells Oskar (Kåre Hedebrant) “I’m not a girl” at one point, although this could be read as being a reference to her supernatural condition. A brief shot of Eli’s scarred, genital-ness groin also features, but to the unwitting viewer just muddies the waters.

The book’s supernatural elements are muted, although one scene where a nascent vampire is attacked by dozens of cats is an addition. Other events, such as Hakan’s death, are simplified—in the book he is vampirised and becomes a menace to Eli and Oskar, while here he commits suicide to avoid betraying Eli. The film also strongly suggests that Hakan met Eli when he was a child himself, and has now grown too old to be useful, indicating that Eli’s relationship with Oskar may be quite predatory.

The remake: Let Me In (2010)

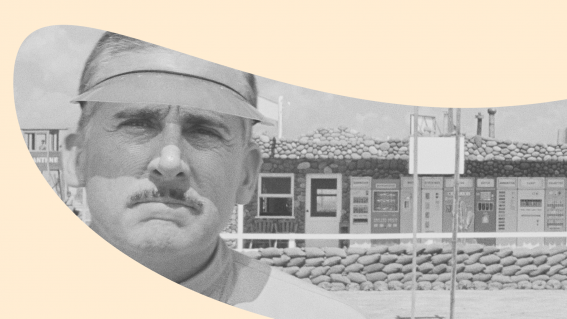

Directed by future Batman wrangler Matt Reeves, Let Me In relocates the action to Los Alamos, NewcMexico, retaining the wintry tone and period setting, and casting rising stars Chloë Grace Moretz and Australia’s Kodi Smit-McPhee as the renamed Abbie and Owen, with Elias Koteas as a cop investigating Abbie’s murders and Richard Jenkins as her companion/servant, Thomas.

In many ways this is a close adaptation; some scenes are shot-for-shot, lines of dialogue are reproduced verbatim, and the general plot is identical. But Reeves kicks things off with Thomas’ death—a much more spectacular and gruesome one at that—eschewing Alfredson’s atmospheric slow-burn. Most other alterations are minor, but there is absolutely no ambiguity about Abbie’s gender.

Let Me In also ups the overt vampire effects (but jettisons the cat scene) and photos explicitly show that Thomas has been with Abbie since he was a child.

The play: Let the Right One In (2013)

Skipping over the 2011 Swedish-language version (all other considerations aside, I don’t read Swede), Jack Thorne’s adaptation whittles down the novel even further than the film adaptations, forefronting the relationship between Oskar and Eli even further.

There’s still a fair amount of blood, depending on the production (both versions I’ve seen were fairly gory without crossing over into Grand Guignol territory). The play also ages up the characters, making them teens instead of children and embellishing the romantic implications of their relationship.

The series: Let the Right One In (2022)

The biggest difference here is simply that there is no Eli and Oskar. Rather, we have Ellie (Madison Taylor Baez) and Isaiah (Ian Foreman). But our focus is on Mark (Demián Bichir), Ellie’s father, who has sought a cure for her vampirism for 10 years and has now returned to New York City with her in tow.

Despite the obvious differences, this latest iteration seems like an expansion of what has gone before, fleshing out characters and developing more complex dynamics: Isaiah’s mother Naomi (Anika Noni Rose), for example, is a cop investigating the series of murders that have occurred since Mark and Ellie hit town.

Whether it manages to hit the heights of its predecessors remains to be seen, but so far it’s yet another Right One.

Let the Right One In: Season 1