Kiwis Sam Neill and John Clarke anchor 1990 Aussie cult comedy classic Death in Brunswick

A chef and a grave digger try to cover up an accidental death in black comedy Death in Brunswick. Grab a takeaway souvlaki, crack open a VB, and dive into historic pre-gentrification Brunswick as Amelia Berry revisits the 1990 cult classic.

Death in Brunswick

Melburnians treat suburbs with the kind of blind passion and disregard for observable fact that most people reserve for star signs or Myers Briggs personality tests.

Suburb X is all marketing managers who shop at uniqlo and overpay for vanilla lattes. Suburb Y is trust fund kids cosplaying derro until their jangle pop band gets picked up on Triple J. You don’t wanna know what people say about Moonee Ponds. Really, ‘living in Melbourne’ is always secondary to living in Footscray, Coburg, St. Kilda, Preston, Brunswick, or etc.

Which is all to explain that ‘Death in Brunswick’ isn’t just a catchy title. Brunswick is more than just a suburb in Melbourne’s inner north. It’s a whole type of guy (albeit a different type of guy in 1990 than in 2023).

OK, enough anthropological background—time for some historical background. In the mid-80s, Boyd Oxlade was working as a gravedigger and decided that writing a novel would be a good way to make some extra cash. Before the novel finds a publisher, he takes it to director John Ruane (also Oxlade’s cousin’s husband), who loves it.

Unable to find major backing for the project, Ruane and Oxlade co-write the screenplay and they shoot it on a shoestring budget with cinematographer Ellery Ryan (Ruane’s wife’s brother/another Oxlade cousin). The result of this scraped together all-in-the-family production? A bona fide Australian cult classic.

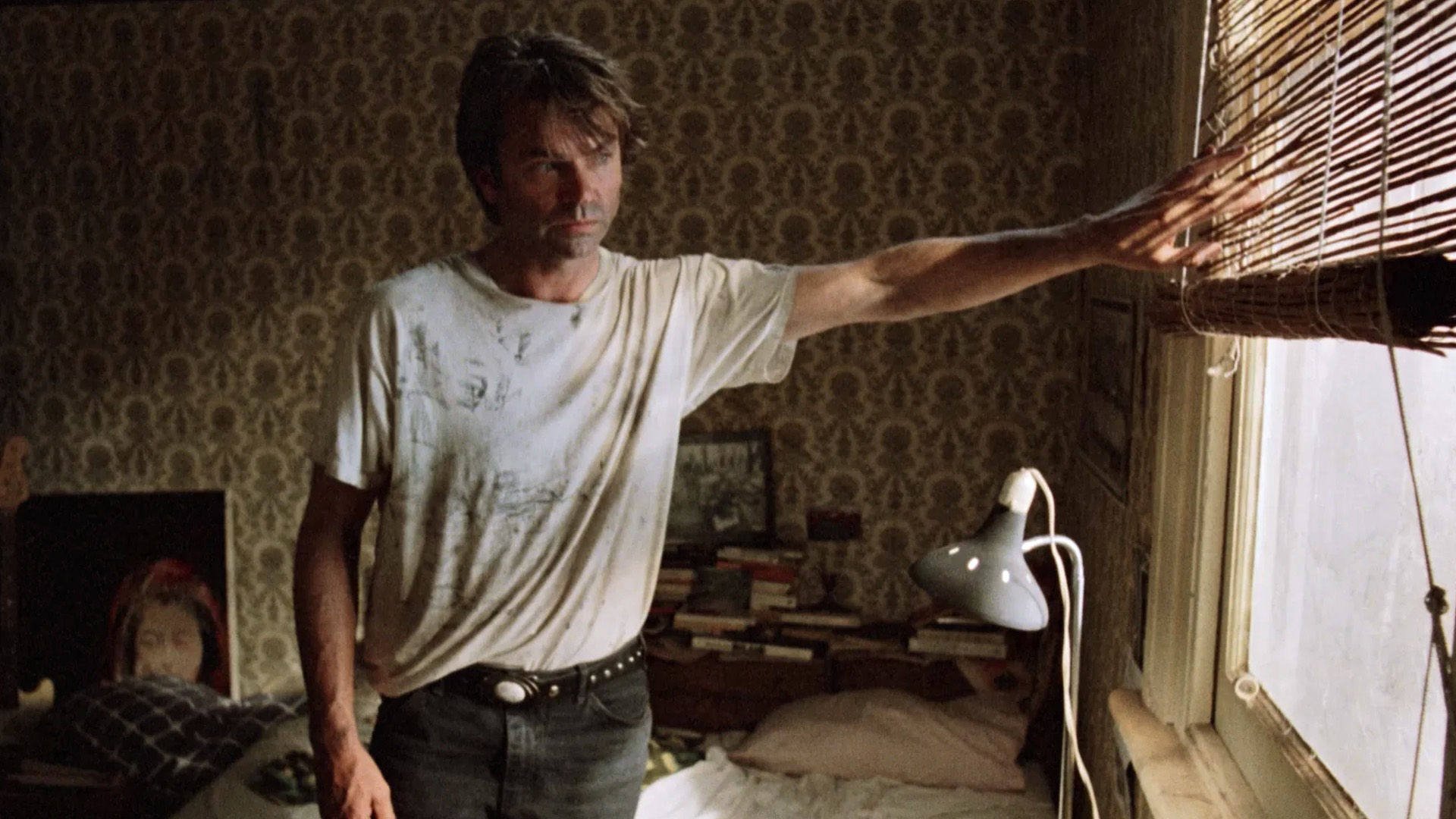

Carl a.k.a Cookie (Sam Neill) is a down-on-his-luck aging rocker. Divorced, living with his mum, and generally just pretty grotty, he lands a job as a cook at a seedy nightclub. From there, he falls in love with the beautiful teen barmaid Sophie (Zoe Carides), accidentally kills his kitchen-hand, gets involved in some late night gravedigging shenanigans with his best mate Dave (John Clarke), accidentally starts some kind of Greek-Turkish gang war, and somehow lives happily ever after.

It all sweats that particular kind of late-80s, early-90s cynicism, where everybody is a bit of a loser, every decision is morally compromised, and life is a series of absurd unpredictable calamities. Coming in 1990, Death in Brunswick really presaged the explosion of brilliant low-budget Australian black comedies in the coming decade—films like Bad Boy Bubby and Muriel’s Wedding.

At the same time, its odd sensibility and deep Australian-ness makes it a kind of mutant synthesis of the previous decades of Aussie cinema. Part New Wave artsy urban surrealism, part Alvin Purple Ozploitation goofery, and partly drawing on the history of Australian racial comedies like They’re a Weird Mob (Fun Fact: John Ruane wrote an episode of ‘Ethnic’ TV comedy classic Acropolis Now).

Strange then, that this most Australian of Australian films should have so many prominent roles filled by New Zealanders.

New Zealander Number One is of course Sam Neill as our lead, Cookie. Doing an edgy no-budget indie might seem a little odd for a man who was about to star in Jurassic Park AND The Piano in 1993. That’s really Sam Neill’s career in a nutshell though—in any given year you’ll find him in two TV movies, one underrated indie classic, and half a Hollywood blockbuster.

Carl really is quintessential Sam Neill though. A little bit the bumbling everyman, a little bit the irresistible heartthrob, with a kind of unsettling menace bubbling underneath—it’s just not often we get to see Neill play such a dropkick. It’s a shame he hasn’t taken on more comedy, because Death in Brunswick shows that Sam Neill can play stupid with rare aplomb.

New Zealander Number Two is the legendary John Clarke—writer, actor, satirist, and creator of Fred Dagg. As Carl’s long-suffering bestie Dave, Clarke is responsible for a lot of the film’s best moments, both in comedy and drama. Whether cowering from the withering stare of even-longer-suffering wife June (Deborah Kennedy) or capering through the graveyard at midnight, Clarke brings a gravitas to his role that helps anchor Death in Brunswick’s weirder moments.

And Number Three is Philip Judd, former Split Enz and Swingers musician and song-writer, responsible for Death in Brunswick’s distinct score. With the main theme played by a fiddle doubled with a plucked mandolin, it’s a folky sound, a little bit Greek, a little bit Celtic (and extremely 1990). Used pretty sparingly, it’s a vital and memorable part of the overall character of Death in Brunswick and one that subtly reinforces the West Side Story cross-cultural romance of it all.

It’s far from an unimpeachable masterpiece. At its centre is a romance that’s basically impossible to root for (Carl: “Why didn’t I meet you years ago?” Sophie: “Probably because I was still in school.”), the pacing is a bit wobbly, and it’s a lot less bloody than the poster or the title would have you believe.

On the other hand, being a little bit shit feels crucial to the DNA of Death in Brunswick. There’s no way a slicker production could have nailed the flat sun-baked expanse of Melbourne suburbia, the smell of spaghetti on lino and stale cigarette smoke, the stop-start pace of life in the sketchier parts of the inner suburbs.

So, grab a takeaway souvlaki, crack open a VB, and dive into historic pre-gentrification Brunswick. If you’re a fan of mullets, leather jackets, gang violence, and Sam Neill, then Death in Brunswick is a cult well worth joining.