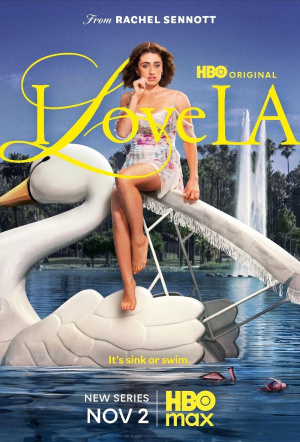

Rachel Sennott is happy to poke fun at herself (and her generation) in I Love LA

Superficiality feels almost part of the point in a show where every emotion is ironic and every word a read.

Can a white millennial woman ever really be free of Lena Dunham’s Girls? I feel, at best, a bore for holding it up against Rachel Sennott’s new HBO series, I Love LA, for comparison; at worst, I’m guilty of the lightly misogynistic crime of conflating women writers when men are allowed to come in as many variations as the labubu.

Yet, at the same time, Hannah “voice of a generation” Horvath achieved something undeniable, wresting disdain for the narcissistic youth away from the boomers and reshaping it as a pointed, self-reflective critique, with an extra dose of pathos. Yes, millennials are obsessed with the performance of intellectualism, and that’s still played out today in Shakespeare and Company tote bags and Letterboxd top four picks.

Sennott is a millennial, technically (she’s 30). Really, we should call her a zillennial, someone whose identity is shaped both by Dunham and her contemporaries, yet who also represents the tectonic cultural shift caused by social media and COVID quarantines. The narcissism is still there—every generation is narcissistic, none of you are special—but it’s shifted forms.

Now, it manifests in the impossible balance: the need to play model, muse, health queen, businesswoman, queer icon, activist, and psychologist, all while never letting slip that any of it’s a conscious effort. In I Love LA, Sennott plays Maia, a talent manager whose influencer client, and old college friend, Tallulah (Odessa A’zion), has relocated to the city from New York to preserve the same IT girl image Maia helped define—and by that I mean she filmed her in a bikini on the subway during COVID.

She’s internet famous because she’s impulsive and barely makes it 24 hours in LA before getting chewed out in a cafe for stealing a socialite’s Balenciaga purse. But said socialite becomes a threat when she tries to get Tallulah cancelled, a move that can only be countered by an apology video delivered with Machiavellian precision. The trick is that Tallulah needs to stay controversial enough to get attention, palatable enough to get sponsorship deals, but not so corporate-friendly as to be labelled “cringe”.

Most audiences won’t really relate to that specific mindfuck, but there’s a truth there that ripples out all the way even to this semi-offline, full-blown millennial: it’s not merely about the performance of depth now, it’s the performance of an entire personality.

So, maybe then, it’s not-so small-minded of me to cite Dunham. Girls and I Love LA feel in conversation with each other because Sennott represents to her generational clique what Dunham represents to her (slight) elders, in the show and beyond it—and in both her online persona, as a former Twitter comedian, and in her characters in Bodies Bodies Bodies (2022) and Bottoms (2023). She is, in short, a democratically elected spokesperson.

It’s clear Sennott, who wrote the opening episode (directed by Lorene Scafaria) and both wrote and directed the final episode, is happy to poke fun at herself. Maia, at one point, insists “everybody thinks that I’m Jewish”—it came to many people’s great shock that Sennott wasn’t, despite playing a Jewish character in Shiva Baby (2020).

And if it’s not about her, it’s definitely about the world around her. Maia’s companions draw from all the primary facets of online culture: Jordan Firstman plays Charlie, a stylist who struggles to upkeep the “mean gay” lifestyle, while True Whitaker plays nepo baby Alani (the actor’s dad happens to be Forest Whitaker), who describes Robert De Niro as “my dad’s friend who taught me how to swim… he was in Shark Tale.”

I can see how audiences might get frustrated with I Love LA for never answering the question of why these people are the way they are, at least not in the way that Girls did. I hope Sennott probes at least a little if we ever get a season two, but, for now, that superficiality feels almost part of the point.

In I Love LA, every emotion is ironic. Every word is a read. Maia ends up pleading to her comparatively normal boyfriend (Josh Hutcherson) that she just wants “a big life”, as if the very act of constant doing, and to be witnessed doing those things by others, can constitute a satisfying existence. There’s no room for the real here. It’s all about the performance.