The Descent turns 20, epically gory and deeply claustrophobic as ever

We revisit a tense, surprising, and imaginatively disgusting modern classic in this excerpt from The Book of Horror: The Anatomy of Fear in Film.

Twenty years since The Descent was released, author Matt Glasby explores how it sets up its subterranean scares in an exclusive extract from the newly revised 2025 edition of The Book of Horror: The Anatomy of Fear in Film.

If there is one guiding principle for survival horror, it is to put the characters in situations so perilous that the audience is on the edge of their seats even before the horror element emerges. In other words, a story that works before the monster appears, should work even better after—depending, of course, on the strength of your monster.

The Descent, the second film from writer/director Neil Marshall (Dog Soldiers), features some unforgettable monsters in the form of ‘crawlers’: blind, cannibalistic humanoids which have evolved undisturbed for centuries underground. Yet the first 50 minutes are about stranding the characters—a group of old female friends/adventurers—in an uncharted cave system with all kinds of dangers lurking around every corner. As sensible Rebecca (Saskia Mulder) points out, ‘Down there it’s pitch black. You can get dehydration, disorientation, claustrophobia, panic attacks, paranoia, hallucinations, visual and aural deterioration.’

‘It was deliberately a three-act concept of introducing the characters and getting them into the cave,’ Marshall told Screen Anarchy. ‘Then we spend the second act just exploring the horror of the cave and caving itself, the claustrophobia and all these other elements. Just milk that for all it’s worth, milk it for all the tension that we can get out of it, and just when you think things can’t get any worse; let’s make them worse.’ Indeed, the results are so effective that Collider’s reviewer Hunter Daniels called the film scarier than ‘having a gun shoved in my mouth’. He should know—this actually happened to him after the screening.

We first meet Sarah (Shauna MacDonald), BFF Beth (Alex Reid) and frenemy Juno (Natalie Mendoza) white-water rafting. On the way home a striking, shockingly staged car crash sees Sarah’s husband Paul (Oliver Milburn) and daughter Jess (Molly Kayll) impaled with pipes, and she wakes up traumatised in hospital, having lost them both.

A year later, the friends head to the Appalachian Mountains (actually Scotland) with sisters Rebecca and Sam (MyAnna Buring), plus Juno’s protégé Holly (Nora-Jane Noone), to explore Boreham Caverns. ‘It’s for tourists,’ complains Holly. ‘Might as well have hand-rails and a fucking gift shop.’ But despite the tough talk, Sarah remains fragile, with Jess’s laughter haunting her waking hours and those pipes piercing her dreams. Indeed, for her, the film is as much about coming to terms with the death of her family as it is about surviving the cave and the crawlers.

In contrast to the early, exploratory moments of the climb, which feature a lush orchestral score and elegant camera moves, Marshall suffuses the underground scenes with claustrophobia. The score turns electronic, the soundtrack breathy and echoey, the cinematography close-up and intrusive. Indeed, cast in the smoky light of a red flare, the cave—actually a series of extraordinary sets built by production designer Simon Bowles at Pinewood Studios—takes on an appropriately hellish hue.

Stuck in a tight tunnel, Sarah panics, so Beth comes back to calm her. ‘The worst thing that could have happened to you has already happened and you’re still here,’ she says. ‘This is just a poxy cave and there’s nothing left to be afraid of, I promise.’ At this, as if brought on by the mention of Sarah’s loss, a deafening burst of music signals the start of a rock-fall, and the pair only just make it to the safety of the next chamber, a backdraft of air sounding like the cave itself is exhaling.

From here things quickly deteriorate. True to form, Juno has actually taken the group off-map—the discovery of ancient climbing gear shows just how far—so nobody knows where they are and no rescue party is looking for them. Holly falls and suffers an open leg fracture, which occasions some impromptu (and ill-advised) surgery from Sam. Then, as Sarah scans a chamber full of animal bones with an infra-red camera, and the group’s unease tips into hysteria, a crawler appears in the darkness behind Beth for a beautifully timed jump scare.

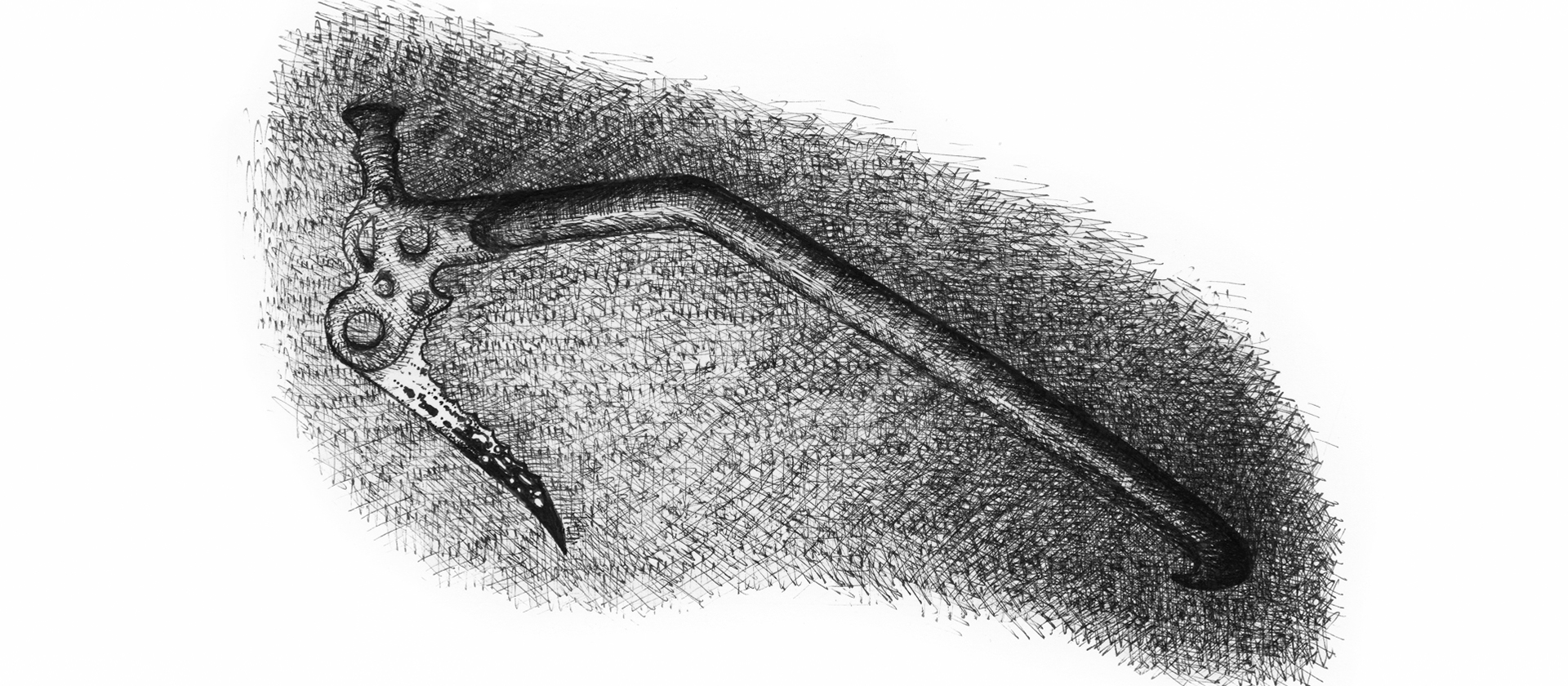

Illustration by Barney Bodoano from The Book of Horror

To increase the surprise, Marshall kept the actors playing the crawlers away from the leads. ‘They had no idea what they were going to look like,’ he told Indie London. ‘They got really on edge about it, so when we did the take and introduced the crawlers, they just snapped and went running off into the dark screaming.’ MacDonald disputes this: ‘Neil kept us apart from them, but because we knew they were Geordie lads dressed up with KY Jelly all over them, we knew it wasn’t going to be that scary.’

Geordie lads or no, Marshall is careful to seed the idea of the crawlers’ existence early on. In the first chamber, as Sarah looks about her, a distant figure squats in the far left-hand corner of the frame. Later, after the rock-fall, Sarah shines her torch over the ceiling ledges, picking out a silhouette that, on the next pass, has disappeared. You could watch the film over and over without catching either of these details, but the effect is that the audience, like the actors, suspects something else is down there in the darkness, even if they are not sure what.

After this first salvo, the shit really hits the fan. Holly is killed and eaten by crawlers, the group splinters, and Juno mortally wounds—then deserts—Beth, in the process revealing both her cowardice and the affair she was having with Sarah’s husband. Not that there is any time for navel-gazing. Directed with customary blood and thunder by Marshall, the confrontations that follow are epically gory, with pick axes hammered into skulls, fingers forced into eye sockets and heads smashed against walls.

The crawlers, meanwhile, are imaginatively disgusting, all white, glistening skin and dribbling mouths, and their evolutionary path is convincing enough that The Descent could be seen as ‘a film about a happy society of monsters being attacked by these girls’, as Marshall told KPBS, ‘because they mete out as much terror and pain as the crawlers ever do.’

Indeed, through the process of the film, we watch Sarah graduating from victim to warrior with gusto. ‘She has to become as primal and as savage as the crawlers,’ said Marshall. ‘When she’s standing there with the fire in one hand and the bone in the other, I just thought, “That’s symbolic of her journey.” She’s almost becoming one of them.’

The Book of Horror: The Anatomy of Fear in Film revised 2025 edition by Matt Glasby, with illustrations by Barney Bodoano, is released on 9 September. Buy it here.