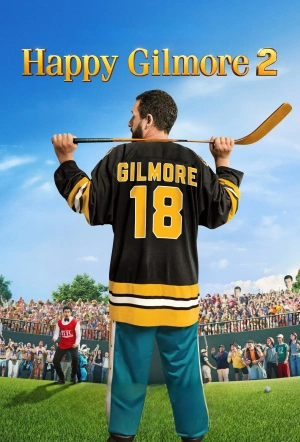

The Happy Gilmore movies give golf a much-needed kick in the nads

Who needs originality when Happy Gilmore 2 has a good old-fashioned comeback narrative, awkward golf swings, and angry outbursts?

Everything about golf is so careful, so mannered, so manicured. The grass is silky smooth; the competitors’ clothes are clinically clean; the game is won through equanimous minds and subtle movements of the hand and wrist. The sport, for a long time, was gagging for somebody to come and vomit all over it, which partly explains the appeal of the Happy Gilmore movies. There’s an obvious dichotomy at play: the sensible and sangfroid associated with golf, versus the explosively unhinged style of Adam Sandler and his eponymous character—a hot-headed wannabe hockey player who found unlikely success on the green.

This fish-out-of-water element was core to the original, but not so much in Kyle Newacheck’s belated sequel, with the now-retired Gilmore a sporting legend. This time there’s a different core element at play: a good old-fashioned comeback narrative. Happy Gilmore 2 begins by bringing us up to speed with the protagonist’s life: he has a big family—with four sons and one daughter—who they lived comfortably until, one tragic day, he whacked a ball right into his wife’s kisser, killing her and leaving him a single parent. Gilmore caught a guy breaking into his Ferrari and beat him up; that guy turned out to be a repo man who sued the pants off him, leaving him financially destitute.

Comeback narratives should push the protagonist down, down, down, really pressing them into the gutter. (This was one of the failings of the recent sports—and comeback—movie F1. It doesn’t dirty the pretty face of Brad Pitt’s race driver by giving him a real downwards trajectory; everything’s an upwards curve.) Despite the hero having nothing left to lose, they need to be reluctant to take up the call for adventure: the second step, marked “refusal of the call,” in Joseph Campbell’s monomyth template. Thus, Gilmore tells somebody trying to lure him out of retirement that “I don’t do golf no more, brother.”

Whenever you hear a line like that, you know it’s Opposite Day—the hero of course will swing back into action, here quite literally. A moral impetus helps to get the ball rolling. Here, Gilmore wants to collect prize money in order to pay for his daughter’s enrolment in the Paris Opera Ballet School. So angry ol’ Happy will return to the green, lose his temper, make some new enemies, whack himself or somebody else in the groin, fall over a few times, swear a bit, that sort of thing.

I particularly enjoyed an early scene depicting the protagonist’s first game since his wife died. He tags along with a group of dickish youngsters, one of whom amusingly—and not inaccurately—describes him as somebody who “looks like he had a divorce five seconds ago.” The protagonist’s first attempt at a swing had me laughing out loud, capped off with a zinger from one of those players: “he rolled further than the ball.” At this point the film is cruising along just fine, with a zippy pace and a healthy hit/miss gag ratio. I didn’t expect it to be this funny. Yeah, it’s not an amazing work of art, but neither was the first one.

We expect a belated sequel to draw lines to the original, but by god this starts to feel forced. The screenwriters (Sandler and Tim Herlihy) insist on returning old characters, even if they’re no longer alive, on several occasions introducing a next-of-kin to take their place, which does nothing to enhance the film or make it funnier. Christopher McDonald is, like in the original, a highlight as Shooter McGavin, who we discover has been deeply unwell and institutionalised. This small but enjoyably twitchy and erratic performance feels, when he loses his temper, almost like an audition tape to play a supervillain; I’m now convinced McDonald would make a ripping Joker.

The aforementioned dichotomy, contrasting golf’s respectability with sheer outlandishness, takes a different form when Happy Gilmore 2 deploys a weird plotline involving a battle to maintain the traditional essence of the sport. The film’s key villain (an impressively offputting Benny Safdie) wants to replace standard golf with “Maxi Golf,” which is more like mini golf—i.e. has fire, moving platforms, maybe a monster truck or two. The Gilmore of yesteryear would surely have wanted this; now he’s part of the system, a cog in the wheel, fighting to maintain tradition. Nobody seems aware of this irony. Gilmore has changed…but, thankfully, he’s still pretty funny.