Twin Peaks predicted the spectacular collapse of America’s myths about itself

It’s not new, but Twin Peaks is as great as ever – maybe more so as we continue to mourn Lynch and his vision.

Everyone talks about the one-of-a-kindness of Twin Peaks. Oft imitated, never replicated. Mother to all of television’s prestige dramas, each of them craning their necks up, trying to taste some of that same greatness. And many have, to some degree. But not in the same way. And not, I’d argue, with the same intensity of feeling. Nothing we’ve seen on the small screen, before or since, can match the existential fright of evil tethered to human flesh, BOB (Frank Silva) crawling up from behind the couch, or blooming into existence as the first atomic bomb test spreads its terrible cloud.

Twin Peaks subverted television, and in doing so legitimised it as a medium capable of “great thought”, because it first knew how it functioned. There would be no Twin Peaks without David Lynch’s co-creator Mark Frost, whose experience on shows like The Six Million Dollar Man and Hill Street Blues allowed the duo’s creation, if you passed it on a speeding bike, to look and move like an old-school procedural.

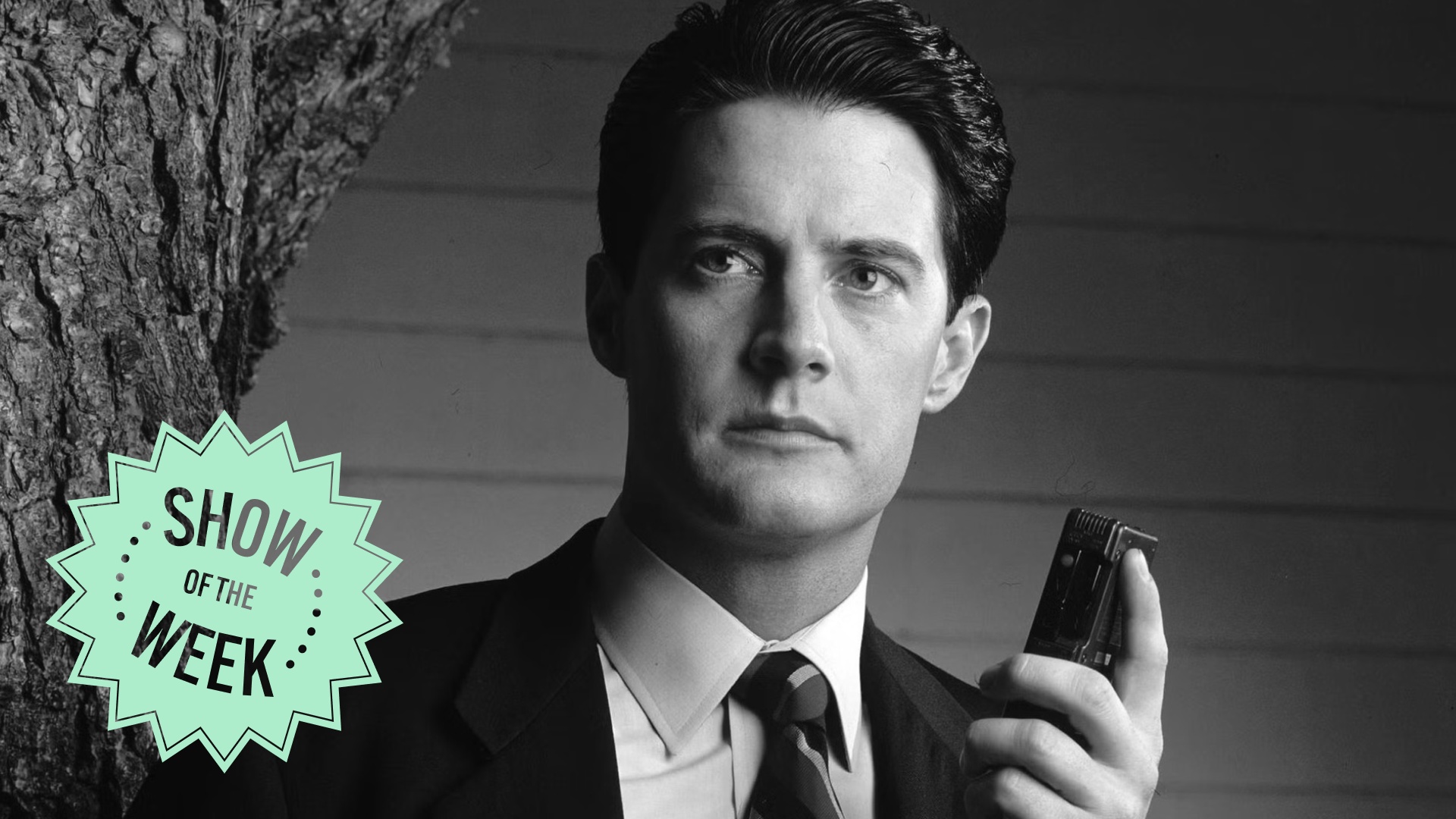

FBI special agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan)—perky, patriotic, and highly caffeinated—arrives to the small town of Twin Peaks, Washington, to investigate the murder of local teen Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee). There are marital affairs, financial schemes, and wayward teens galore. All the soap opera staples are here, all the strife and misery paraded around for our own entertainment.

Related reading:

* A spoiler-heavy unpacking of The Rehearsal’s season 2 finale

* A newly liberated psyche comes to understand itself in warm, funny Murderbot

* The best shows of 2025 so far… and where to watch them

But something dark is moving deep in the woods: the Black Lodge, the red room, BOB, whatever you want to label it. The shaken, bloodied body of Ronette (Phoebe Augustine) stumbles across a rail bridge like a Fury shot out of hell. We can say this violence comes from another realm, blame BOB for Leland Palmer’s (Ray Wise) murder of his own daughter, but that divide between the other world and ours is as thin as paper because we will it to be so.

As Lynch beautifully underlined in his companion film Fire Walk With Me, we can try to disassociate, to delude ourselves that the evil comes from outside—but behind well-polished doors, after hours and off the clock, the vulnerable are harmed and the violence ferments.

The inglorious fate of season two, in which viewers jumped ship en masse after the network pushed for Frost and Lynch to reveal Laura’s killer, subsequently driving the pair away and leaving the show largely in the hands of pale imitators, creates its own kind of weird poetry. Audiences came to Twin Peaks craving certainty. And when they got it, they lost interest, invested only in the “who” of evil, the scapegoat, and not the thornier “why”.

When Frost and Lynch circled back 25 or so years later, as promised by Laura on screen, for 2017’s The Return, they delivered what feels like both closure and vengeance. It ends and it doesn’t end. Its characters are stuck, unable to move on but unable to go back. The beautiful, wilful Audrey Horne (Sherilyn Fenn) descends into madness. We finally meet Diane (Laura Dern), the invisible receiver of all of Dale’s recorded cassette tapes, only she’s not sweet and wholesome like we imagined her. She’s a spitfire.

Dale’s mind, meanwhile, has been dumped into another body, left without agency or control. When he’s finally at one with himself again, his attempt to intervene in Laura’s fate proves futile. He’s left unsure where he is or when, faced only with Laura’s death rattle of a scream. “There are some things that will change. The past dictates the future,” he warns us. The evil of then cannot be subdued or avoided. It may wear different faces but it breathes the same.

Lynch, it’s always said, was ahead of his time. He knew how to be absurd and morbid in ways that predicted the onslaught on the modern brain, as it oscillates on social media timelines between massacres and cat memes, unable to reckon with both yet somehow processing both simultaneously. Fish in the percolator. She’s dead, wrapped in plastic. But he also seemed to know the road ahead, how every myth America wrote about itself, the white picket fences and cherry pies, would collapse in spectacular fashion.

We’re living now, it seems, through that spectacular collapse. It’s what made Lynch’s passing earlier this year feel especially cruel. He’s gone now, with that wonderful brain of his, that could capture what it’s like to be alive in the face of the unfathomable, but inevitable monstrousness. To feel its sick, dark pressures, but to remember too, deep down, that love is still a fairytale worth believing in. It’s as if he knew how to conjure the feeling of something we’re maybe now only starting to find the words for.