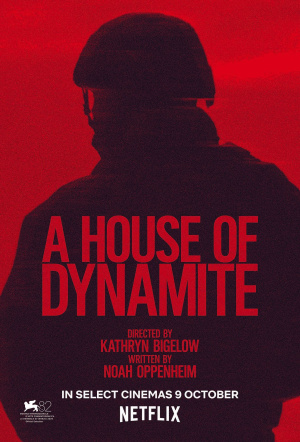

A House of Dynamite joins the ranks of the most nervy nuke thrillers

Decades after the Cold War, a nuclear holocaust is closer than we’d like to admit. As close as 18 minutes, in Kathryn Bigelow’s disturbing new film.

There might be no cataclysm that film and TV better helped people to understand through various depictions than nuclear war. Since On the Beach ushered in the serious contemplation of nuclear annihilation and the limits of deterrence onscreen in 1959, different eras have engaged with the nuclear threat in a variety of ways, an ongoing conversation now joined by Kathryn Bigelow’s tense A House of Dynamite. While most reflect the tempo of their time, the very best movies on this topic helped to actively shape the public attitudes, and this very much seems Bigelow’s intent here.

In echoes of Sidney Lumet’s superb and urgent 1964 pic Fail-Safe, A House of Dynamite follows the US government procedures that spring into action when a sudden nuclear threat emerges. But whereas Fail-Safe considers a scenario in which a communication error sends six US nuclear bombers on a mission to bomb Moscow—with slim chance of recall—Bigelow’s film depicts the US government’s response to an intercontinental ballistic missile launch aimed at the continental United States.

Much has changed in the sixty-plus years since Lumet’s film, which controversially raised the prospect of the ‘good guys’ accidentally causing global catastrophe. The Cold War is, in theory, long over and fingers on launch buttons supposedly less itchy. But, as A House of Dynamite confirms, the nuclear arsenals are growing, not shrinking (some estimates put the total global stockpile of warheads at just under 10,000). And so the panic about what to do and how adversaries might respond feels very similar onscreen in both pictures, despite many technological advances in filmmaking as well as the war rooms depicted.

Each of the films considers strategic second-guessing taking place under the intense pressure of a limited amount of time. Their characters face the prospect of making a scarcely comprehensible decision about whether to unleash the whole US nuclear arsenal. At least in Fail-Safe, the US military knows what’s going on (cold comfort, given the consequences)—in A House of Dynamite, the launcher of the missile is unknown, and whether it carries a nuclear payload is a mystery too… but what becomes certain as its trajectory is confirmed is that it will strike a US city.

Bigelow focuses on examining an 18-minute window between launch and impact, revisiting this crucial period of time—that might dictate humanity’s survival or eradication—from several perspectives. “I thought of the idea of these separate chapters, each relaying the same 18 minutes from a different vantage point,” Netflix quotes Bigelow as saying, “starting with the foot soldiers, if you will, and moving up the chain of command to the decision-maker at the top, the president.”

The film jumps from an Alaskan anti-ballistic missile launch site to the White House Situation Room, as well as the Pentagon, emergency bunkers, and the extraction of the President from a basketball court media appearance as the missile approaches—with the tension never ebbing.

Creatively and stylistically this feels in keeping with previous Bigelow films The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty, keeping a steely eye on the details. And, crucially, the limited role that individuals have to play in systems and processes intended for our survival but threatening extinction—something that applies to no-one more in the film than Idris Elba’s President, who finds himself presented with a ring-binder of retaliatory strike options that, as he exclaims, looks like a diner menu.

Fail-Safe

Dr Strangelove

But don’t mistake this for a comedy. There’s been plenty of dark satire directed at the topic—like Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, also released in 1964 and overshadowing the more realistic and therefore harrowing Fail-Safe. And by the 1980s, a bleakly funny nuclear nihilism held sway in a lot of films, even those that captured elements of the heartbreaking terror of impending doom like 1988’s Miracle Mile. Director Steve De Jarnatt’s cult classic (a fave of Charlie Brooker’s) doesn’t skimp on panic and drama as news of an incoming nuclear strike spreads across LA—but it’s paired with the sort of 80s anti-authoritarian sentiment and absurdity to be found in films like (not technically about nukes, but kinda) Repo Man.

Of course, alongside these sorts of films, there’s the ever-increasing post-apocalyptic sci-fi genre where nukes had created the backdrop to everything from Planet of the Apes to A Boy and His Dog. Sometimes you have to laugh in service of a deeper understanding—sometimes you just need the world to have been blown to smithereens to set a sarcastic story in its aftermath, something still seen today in Prime Video series Fallout.

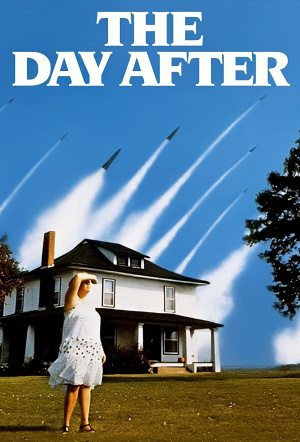

The Day After

The Day After

At other times, a more literal and realistic depiction of nuclear war was needed to rattle the cages of the public and then the powers that be. You’d be hard-pressed to count the number of nightmares inspired by two such ‘80s productions (if such a calculation were even possible). I have vivid recollections of 1983’s The Day After, set in Kansas and watched by over 100 million Americans. We all saw what it looked like to see US missiles flying into the sky, the panic of the countdown to Russian strikes, and a realistic depiction of nuclear war’s consequences on everyday heartland USA. The societal impact? Massive—including on then-President Ronald Reagan, whose diary of the time noted it had changed his opinion about nuclear war.

Across the Atlantic the following year, British viewers were equally traumatised by Sheffield-set Threads. It shows the medical, economic, social, and environmental consequences of nuclear war—from the panic in the days before it happens, through to the futility of post-war planning. Like The Day After, it helped to coalesce thinking on nuclear war—both films providing plausible and tangible depictions of how ordinary people would be affected/obliterated/suffer horrible radiation deaths.

Threads

Threads

In more recent decades, particularly with advances in special effects, we’ve perhaps become a bit too focused on the spectacle of disaster (see Roland Emmerich’s many destructions of cities onscreen, for instance). It’s easy, then, to see why Bigelow chooses not to build towards a third-act special effects armageddon in A House of Dynamite. Besides, we already have her former creative and romantic partner James Cameron’s memorable nuke nightmare of Terminator 2: Judgment Day to refer to.

Like the characters in A House of Dynamite, we are left guessing about a lot as the credits roll. That doesn’t dilute the film’s impact, or the anxiety of its repeating 18-minute launch window. But it does keep the focus on how quickly our world could still turn to irradiated shit, how fucking insane this weaponry and the tactics around its use are, and what the people inside these response structures might have to contend with.

Perhaps most terrifying of all—A House of Dynamite is populated by competent people who know what they’re doing, and yet the world still races towards potential oblivion across the course of the film. In an era where MAGA fealty has replaced skill as a factor in White House appointments, when the military is run by a Botoxed Fox News host, and as the US accelerates the collapse of a global rules-based order, it’s perhaps easier than ever to fathom how this whole house of dynamite could go up in a big bang before we even know it.

Don’t look away, Bigelow seems to be saying. There might not be any more of a conclusion or thesis present than that—but based on the chilling experience of watching A House of Dynamite, this may be exactly what the present moment calls for.