A newly liberated psyche comes to understand itself in warm, funny Murderbot

In classic sci-fi style, new series covers all matters of capitalism, freedom, and personal identity.

Clarisse Loughrey’s Show of the Week column spotlights a new show to watch or skip. This week: Murderbot captures the neurodivergent experience to a tee without it expressly being about it.

It’s a fairly common autistic experience to see yourself in a fictional robot. If it’s not Data in Star Trek, it’s WALL-E, Andy in Alien: Romulus, or any droid of choice from the Star Wars franchise (my pick? Rogue One and Andor’s K-2SO). It’s a tricky situation. If an allistic person starts drawing comparisons between a neurodevelopmental disability and literal synthetic existence—well, we’re entering the dangerous territory of dehumanisation, and all the alienation and abuse it entails.

Yet, when an autistic person is trying to rationalise their own experience of the world, it does often feel like being the one android on the space mission: forced to observe from a distance, to have none of the social tact come naturally, instead working through norms like an instruction manual, baffled as to why a rule might apply here and not there, feeling adrift in a terribly illogical universe.

In fiction, robots can be verbal or non-verbal, they can be adept or deeply anxious. Autistic people can be some of these things or all of these things, sometimes depending on the day. In fiction, robots often end up as autistic-coded because, when their writers look around them for what the Tyrell Corporation might call “more human than human”, what they’re really looking for is something they interpret as incongruous behaviour. Or, in other words, neurodivergent behaviour.

It’s hard to outline the precise good and bad about this kind of representation, partially because autism itself is such a wide spectrum, encompassing so many different experiences that do and don’t adhere to what we see on screen, and partially because there’s a question of who that representation is meant to serve. I don’t think autistic-coded robots do much at all for changing an allistic audience’s perception of autism, because allistic audiences rarely even clock the coding in the first place.

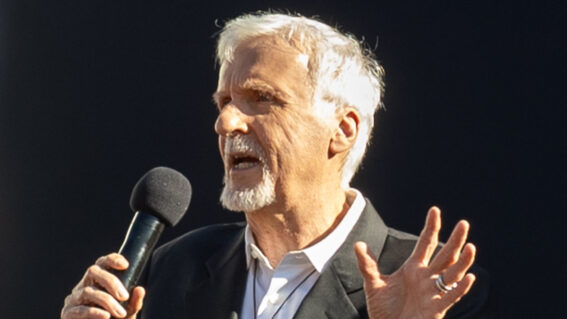

But I do think they can be a comfort for autistic people just wanting to see a little bit of their world in the art they consume. Or, in the case of Martha Wells’s The Murderbot Diaries, now adapted into a warm and funny Apple TV+ series starring Alexander Skarsgård, helping their own creator realise they themselves might be on the spectrum. “I didn’t realise how non-neurotypical I was until I started writing Murderbot,” the author told New Scientist. “I was thinking that explained a lot about my life actually.”

Whether allistic audiences pick up on it or not, Murderbot captures the neurodivergent experience to a tee without it expressly being about the neurodivergent experience. Murderbot (Skarsgård), a security unit, gave itself the name after managing to override its governor module and granting itself free will.

Realising that if anyone at The Company found out, it’d be immediately branded as malfunctioning and melted into oblivion, Murderbot instead lets itself be hired by a band of well-meaning hippies from Preservation Alliance, who have reluctantly loaned out corporate equipment in order to conduct a survey on a distant planet. Something sinister is afoot on its surface and, in classic sci-fi style, the series covers all matters of capitalism, freedom, and personal identity.

This is a newly liberated psyche coming to understand itself for the first time but, in doing so, learning a few crucial aspects of its personality: it hates eye contact, it finds human behaviour deeply weird and occasionally repulsive, and—having downloaded 7,532 hours of content onto its system—it would much rather be watching its favourite show, The Rise and Fall of Sanctuary Moon, than doing literally anything else.

The series is not only its special interest, and the only steady source of dopamine at its disposal, but a roadmap for how to understand emotions and navigate certain situations. It quotes from it all the time and gets its best ideas from its plot lines. In fact, it’s really quite distressing to Murderbot when real people don’t react like the characters on Sanctuary Moon.

And, while one of the foundational beliefs of the Preservation Alliance is that any sentient construct deserves the rights of personhood, that doesn’t necessarily translate to them actually treating Murderbot as one of their own. Even the most well-meaning allistics can be guilty of this—the feeling that there’s something “off” about someone.

“I look at you and I feel something’s wrong,” one of the team’s scientists, Gurathin (David Dastmalchian), tells the synthetic. Murderbot points out Gurathin also has an issue with eye contact. He struggles to express his emotions, too, avoids physical affection, and happens to be a modified human with cybernetic implants that let him interface directly with computer systems.

That’s an unusual thing to see in a story with an autistic-coded robot: another autistic-coded character whose distrustful, at times hostile, attitude reflects how vastly different two neurodivergent people’s experiences can be and how conflict can sometimes arise when higher masking autistic people project their frustrations with their own self-limitations onto lower masking autistic people. “What’s it like to be you?” Gurathin asks at one point. “I don’t know what it’s like not to be me,’ Murderbot responds. And there’s no more explaining it, really. You either relate to Murderbot or you don’t.