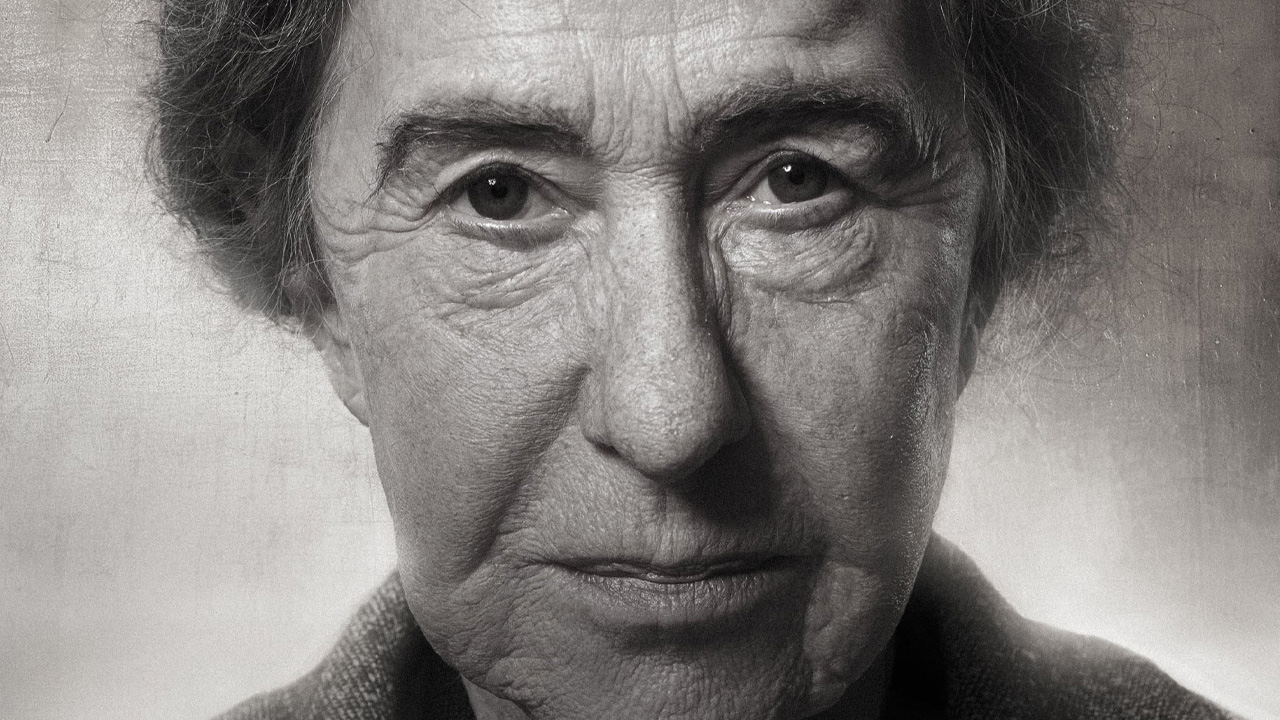

Helen Mirren on the controversy of becoming Israeli PM Golda Meir

“The discussion has to be had,” Mirren says of appropriate casting and the responsibilities of acting.

Screen legend Helen Mirren talks to Stephen A Russell about her latest role in Golda, where she – somewhat controversially – plays the ‘Iron Lady of Israel’ Golda Meir during the Yom Kippur War. “The discussion has to be had,” Mirren says of appropriate casting and the responsibilities of acting.

There’s a flurry of panic in a sleek suite somewhere on the upper floors of Berlin’s palatial Hotel Adlon Kempinski, overlooking the Brandenburg Gate, when word comes through that Dame Helen Mirren’s schedule has gone haywire. There’s a chance we might have only moments to unpack the complex politics behind Golda—Oscar-winning director Guy Nattiv’s biopic about Israel’s first (and only) woman Prime Minister, Golda Meir—before Mirren has to dash to catch a jet.

Thankfully it all works out as Mirren sweeps, smiling graciously, into the room. Sporting a luminous purple dress crowned with a sparkling tiara, her get-up brings to mind arguably her most famous role, as the late British monarch in The Queen. But there’s no sense of imperiousness to match, despite Mirren’s storied career stretching from her first credit in Australian director Don Levy’s startling experimental feature Herostratus in 1967, past the infamy of Tinto Brass’ Caligula (1979) and the majesty of John Boorman’s Excalibur (1981) all the way up to Shazam! Fury of the Gods via The Fast and the Furious films.

Mirren is exactly as you’d imagine; smart, generous and sassy, taking it in her stride when asked, straight-up, what the responsibilities are in depicting a Prime Minister whose legacy is fraught enough in Israel, never mind more broadly in the Middle East, particularly because of her role in the brutal 20-day Yom Kippur/Ramadan War with Egypt and Syria in 1973.

“I do remember Golda becoming Prime Minister, but I don’t necessarily remember the Yom Kippur War,” Mirren recalls of her living memory of this deadly conflict, which played out when she was in her late twenties, noting with a wry and mischievous chuckle that she was mostly focused on securing her next role. “I really had to dive into both who Golda was, and what the implications of the war were. There’s an incredible challenge and a danger to it, and I was really drawn to the way Guy presented it as a dark, intense poem, in a way, about a person and also a conflict.”

Courting controversy

Mirren, who spent time on a kibbutz in the ’60s, is not Jewish, but has played so several times, including a Mossad agent in John Madden’s The Debt (2010) and an Austrian refugee fighting for the return of her family’s art stolen by the Nazis in Simon Curtis’ 2015 biopic Woman in Gold. But the conversation around who gets to play who is rapidly evolving, and her casting seemed to rattle more cages this time. “It’s a legitimate question,” she says. “The whole idea is changing all the time, and we’re in the process, still. I think the discussion has to be had, and there are arguments on both sides. And Guy makes a great argument, which is that [from his perspective] he doesn’t want Israeli actors only ever playing Israelis.”

But she is undoubtedly for opening up opportunities to those who have been purposefully shut out, recalling a shocking event during her brief stint on the board of London’s esteemed, though certainly stuffy, Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA). “There was this older guy who was the chairman of the board, and we were talking about the need to bring more Black actors into RADA, that they weren’t being given opportunities. And he literally sat there and said, ‘Well, we can’t do that. It would be cruel because there aren’t the roles for them’.”

Mirren sits in the shocked pause that follows my gasp. “I left the board, resigned that day.”

She knew stepping into Golda’s famously clumpy shoes [and heavy prosthetics] would raise eyebrows and reiterate her belief her decisions are open for public debate. “You’re laying yourself open to profound criticism. You could blow it terribly. She’s a complicated and incredibly important character in history. So we’re negotiating a bit of a minefield.”

Call to duty

Interestingly, Israel-born, Los Angeles-based Nattiv reveals that it was Meir’s grandson, Gidi, who first suggested Mirren for the role. When the director met her in LA, he was convinced she had what it took to get it right. “I felt like I was meeting a family member, like she was my aunt,” he says. “So for me, it wasn’t even a question. If I look at [the cast of] Spielberg’s The Fabelmans, almost his entire family is [played by] non-Jews.”

Nattiv says he has the authenticity, as a third-generation relative of Holocaust survivors, to tell the story the way he wanted to. He wasn’t shy of digging deep into the controversies surrounding Meir, either. “I was born just a few months before the Yom Kippur War, in May 1973, and my mother went with me, as a baby, to the shelter and my father went to the war,” he says. “So I grew up with this notion of Golda and that’s what I wanted to disassemble.”

Though much of the war’s missteps were pinned on Meir, leading to her eventual resignation, the film explores how she received faulty information from the men in her war cabinet and from the intelligence services. “She had a part of this debacle, but she’s not the only one, and no one knew that she had cancer,” Nattiv says. “She was an anti-hero.”

One that Mirren couldn’t say no to, literally disappearing below layers of intense makeup daily to become her, all the while listening to the Ukrainian-born Meir’s American-inflected accent (her family moved to the US as a child) on her headphones. And yes, she’s aware many non-Jewish people, too, would rather she not play a role like this. “I was a post-Second World War child, and after what was done to the Jewish people, I feel profoundly that the State of Israel must be,” she says. “But I also believe that the Palestinian people have history and existence and have to be as well. So there has to be, I hope, a solution. I know, from being British and the issue in Northern Ireland, that these terrible territorial battles go on for centuries and that the twin idiocies of racism and nationalism can take human beings down terrible roads.”

Forging a legacy

What were Mirren’s biggest challenges in portraying Meir? “The voice and the walk,” she says. “There was something so specific about Golda’s walk, and I don’t think I ever quite got there. But I really tried… There was an intention in her walk. And a lack of vanity. She went from this point to that point, and that was in her psychology, I believe, as well.”

Asked which roles have stuck with her most in her 56-year career, she flips the question. “It’s not what I think, it’s what other people think, really, and obviously The Queen was one of them,” Mirren says of fans’ adoration for her depiction of another complicated head of state embroiled in crisis. “I was angsting about that, and of course, she was still alive. But what relaxed me was [the idea that] I’m an artist, and I’m doing a portrait that’s my artistic understanding of this person.”

She hopes audiences will embrace her turn as Golda too. “Every film is a different journey, and Golda will be one of my most important journeys, I think.”

Originally published by Flicks on September 14, 2023