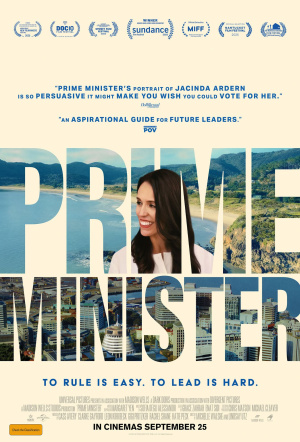

The making of revealing, intimate Jacinda Ardern doco Prime Minister

We speak with co-director Michelle Walshe about Prime Minister, a powerful combo of intimate archive and reflective contemporary interviews.

Jacinda Ardern’s time as New Zealand Prime Minister coincided with some of the most tragic and turbulent events in modern Aotearoa history. While initially domestic—the vile terrorist attack in Ōtautahi Christchurch, the same year’s deadly Whakaari/White Island eruption—Aotearoa soon joined the whole world in facing the challenge of the COVID pandemic. Fragmenting societies globally, with a worldwide death toll in the millions, COVID was met by a spectacular public health response in Aotearoa, though reactions to Ardern’s leadership also revealed a vicious, threatening and misogynist streak beneath the fragile veneer of our society.

It was a lot for any of us to deal with, let alone a relatively young woman who carried the responsibility of being the leader of a nation. For Michelle Walshe, co-director of new doco Prime Minister, which chronicles and reflects on Ardern’s time in office, the time this film covers was an intense experience (like it was for all of us). She lived in New York for part of it, her husband was stuck on the other side of the world—a lot changed between what she calls the beautiful, optimistic time when we saw a 37-year-old have a baby while in office, going on to get worldwide attention before the global crisis exploded.

“Firstly, it’s a New Zealand story,” Walshe says of Prime Minister, “and I think that was in the forefront of my mind all the time”. It’s also a universal story about leadership, she adds, describing her doco as a once-in-a-generation film where we get extraordinary access to a world leader through not only her own lens, but the lens of her partner.

There’s a lot of footage shot by Clarke Gayford over the period, Ardern’s long-term partner who was beside her through the journey of becoming a PM and also a mum. “Who has a broadcaster living in the house when you’re a world leader?” Walshe pondes rhetorically. “I don’t know that we’ll ever see that again.” These intimate, observational moments pierce the veil of composure and communication skills that we saw from public podiums, revealing a lot about the pressures behind the scenes and adding some lovely context to the pair’s relationship.

Related reading:

* Our favourite films of NZIFF 2025

* If you can see Gaylene Preston’s Grace: A Prayer for Peace on a big screen, you absolutely must

* Some of our recent festival faves are back in cinemas now

Also captured during the period, adding further context to the public-facing PM, are audio clips recorded by the Alexander Turnbull Library’s Political Diaries project. Since the 1980s, and across 4000-odd interviews, NZ Prime Ministers and other leading political figures have spoken with oral historians about their day-to-day challenges—and with openness and candour that can only come from strict secrecy of the contents. As a historical record, that lends these conversations immense weight—to be able to include Ardern’s unvarnished comments on recent history in this new doco is a massive coup.

Walshe describes having access to audio from the project, now sadly having come to an end, as incredibly significant. “That gift of the Alexander Turnbull Library material was made more powerful by the fact that it’s not normally released until the politicians, in this case, die,” Walshe explains. “So what you have are these candid reflections that you just would never get to hear,” She can’t wait to discover what else is in that vault over time, and reflects that in terms of the value of capturing history, that’s what the filmmakers were trying to do with Prime Minister, too.

The archive footage available to the documentary came to about 200 hours, much of it a vault of footage supplied by Gayford. That’s supplemented in Prime Minister by new material, including reflective interviews with Ardern filmed by Walshe’s husband Leon Kirkbeck. Alongside US co-director Lindsay Utz, Walshe lent into the film being a first-person account (and second-person with Gayford) of a leader navigating through some of the world’s biggest crises. With so much material, what they selected in their first pass came to around 13 hours, and Walshe credits Utz with bringing a different perspective, helping to identity which elements felt most important, unique and special—not just from an Aotearoa viewpoint.

All of which prompted me to enquire about what good stuff didn’t make the final cut. Some intimate family moments come to mind first for Walshe. She recalls the tough conversations really starting once the film reached the two-and-a-half-hour mark, and having to make difficult choices about what to let go. “If I could have had my way, the typical director’s cut would have been half an hour longer and slower,” Walshe admits.

So, what did Walshe see change in Ardern over the film’s timeline? The co-director muses that you can observe Ardern grow into someone who’s more confident, more reflective, and probably has more resolve about the values and principles that guide her. I suggest there’s a lot more experience with media that comes to the fore, too, and ask Walshe if she found different versions, or default modes, of Ardern as she spent time in front of cameras.

“We’re very lucky,” Walshe responds: “Because over the years, we got to know Jacinda, and so when we sat down for those interviews, she actually caught me off guard. Normally when you sit down with subjects for a documentary, it can take hours to unearth what they really think about things.” Walshe’s previous feature doco Chasing Great with Richie McCaw is one of the examples of environments she’s spent a lot of time in “where people are very, good at giving very well-versed answers for media, and so I feel like that’s become something I’ve worked really hard on—being able to elicit more human responses or more intimate reflections.”

“Jacinda took me a little bit off guard, because she was so ready to speak openly. It’s very intimate. It’s very unfiltered. And so in this instance, I’d have to say I was probably really taken aback by how open she wanted to be.”

“I don’t want to give away the film, but in that last, I don’t know, 20 seconds of the film, this beautiful, raw moment happens. And that happened very early in one of my interviews in Boston, and it really took me back. So I think ‘Gosh, we’re 15 minutes in, and you’re wanting to be so open.’”

For Walshe, a major part of Ardern’s legacy, and something captured in Prime Minister, is how she has been brave and unapologetic in the way that she’s led—and not done things the way everybody else has. Something Walshe says was really striking to observe in a female leader. “I distinctly remember seeing her take a baby into the halls of power and not apologise for that,” the director recalls. “And that might sound funny, but it was really profound to me. I was like, ‘Can you be a mother and not apologise in a work context for that?’”

“I spent most of my career trying not to talk about my kids in case it was perceived that I was distracted. And here she was running a country and breastfeeding at a desk with zero apology. And at 37 I was like, ‘What the heck am I watching here?’”

That was the moment Walshe realised following Ardern’s time as PM would yield something special—“but again, we had no idea where this film was going to go.”

THIS INTERVIEW HAS BEEN EDITED FOR LENGTH AND CLARITY AND WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED 20 SEPTEMBER 2025