R-rated Netflix comedy Fixed disrupts the doggo discourse

This crude animated comedy might just be Genndy Tartakovsky’s most challenging project yet.

A dog has one last hurrah in the big city before he gets neutered in Genndy Tartakovsky’s adults-only comedy flick Fixed. It’s raunchy, it’s disgusting and, as Liam Maguren writes, might just change the way we look at dogs for the better.

Animation legend Genndy Tartakovsky recently challenged audiences with wordless, ruthless, R-rated, Emmy-winning series Primal. However, his latest doggy comedy feature Fixed might be his most challenging project yet—not just for its juvenile sense of humour, but also its defiant stance on doggo-ness.

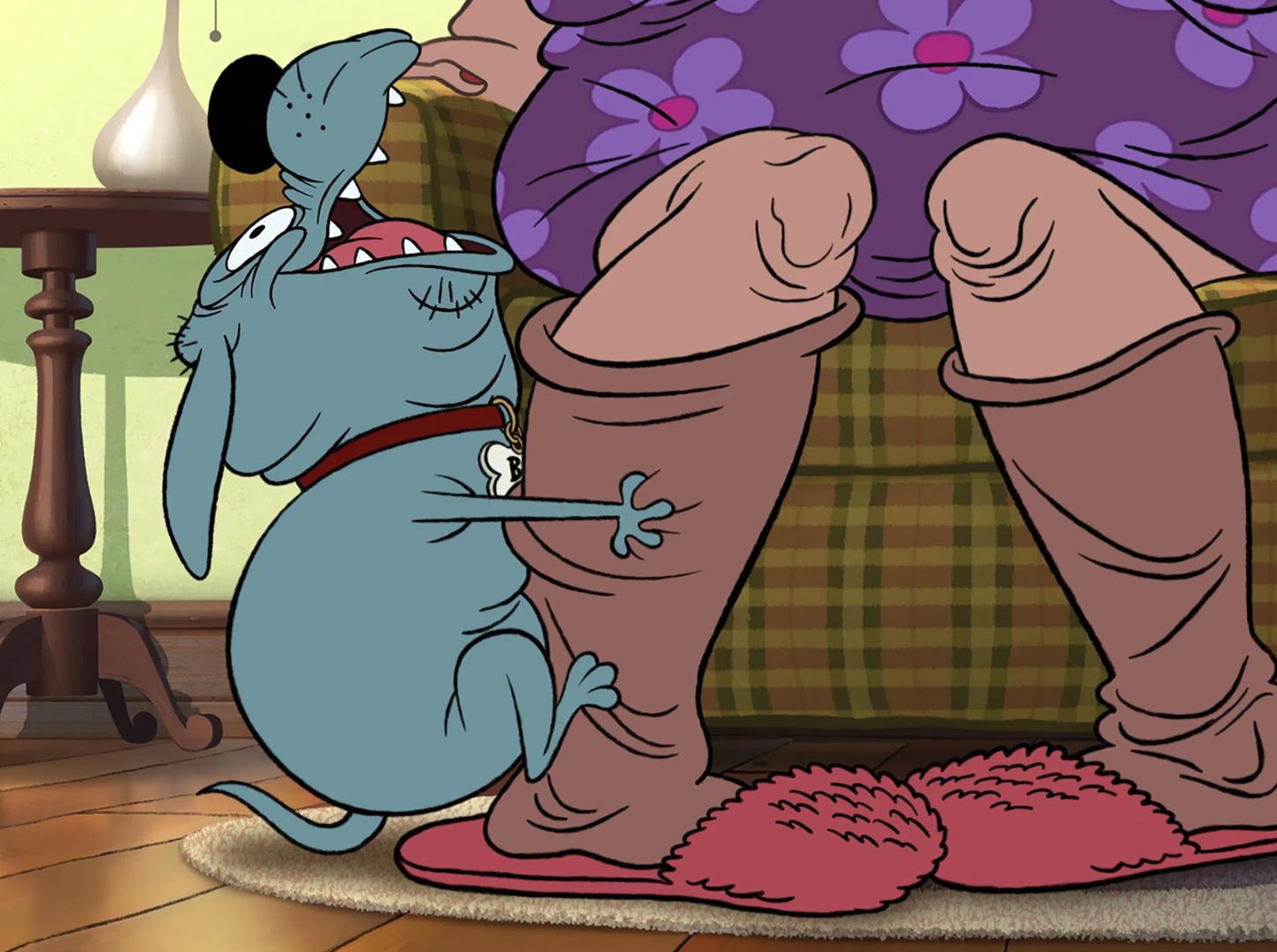

The film’s essentially a riff on the bachelor party genre—if you swap dudes for dogs and marriage for losing your testicles. Realising he has only 24 hours before getting the chop, mangy mutt Bull sneaks out of home and aims to go wild in the big city with his mates. This means scrapping with alley cats, murdering squirrels, pissing wherever, shitting wherever, and sniffing around a canine strip club.

If you’re not in the market for the fruit of gags hanging as low as Bull’s nut sack—which you will see a lot of—your patience will be tested for the first 20 minutes. Hearing a dog say “Fuck” isn’t as crack-up as the film thinks it is and obvious jokes like a show dog being the “winner’s bitch” will make eyes roll so hard, they could power vehicles.

Stomach that, however, and you’ll see the comedy gradually lean towards the film’s strongest assets: the animation and character design. Moments of exceptional facial work, like one dog who gets hit so hard with skunk spray that his pupils scream, recall Ren & Stimpy at its most insane while the contrasting shapes of Bull and his love interest Honey—he’s pudgy like a pile of water balloons while her contours portray the length and rigidity of a dagger—mirrors the visual absurdity of something like The Triplets of Belleville.

Fixed

The Triplets of Belleville

The spirit of the film, however, aligns most closely to Fritz the Cat, Ralph Bakshi’s 1972 cult classic of a womanising feline art student in late-‘60s Harlem who’s as pretentious as he is perverted. At the time, Walt Disney aggressively positioned animated cinema to require unattainably high budgets and target young audiences. Bakshi rebelled against this myopic view, opting instead to use a small-scale production for strictly adults-only experiences.

Sex, swearing, and savagery—it was all there to shock and defy the censors and proved a natural fit for Bakshi’s voice. Unabashedly vocal about his political stance, Bakshi’s messages about social injustices and America’s love for warfare were delivered as subtlety as a can of mace to the eye.

Fixed isn’t out here to make such weighty statements, but its dedication to raunchiness does a lot to disrupt the doggo discourse—‘doggo’, in this case, referring to the sweet, innocent, naïve, internet-friendly personality we ascribe to canines. Tartakovsky’s more interested in showing the sides of these animals we try to ignore.

Dog buttholes, in particular, are everywhere in this film. That might seem crude, but at least it’s honest, unlike Disney’s Zootopia which had a whole nude gag sans the actual nudity parts, or Tom Hooper’s butthole-less Cats which caused enough of an uproar to spawn an entire fan-made Butthole Cut.

Bafflingly, they tried to put in a genital examination gag in 2018’s supposedly-for-children live-action comedy Show Dogs. The scene involves a dog not consenting to having his genitals looked at and told to go into a “Zen place” to mentally escape from the situation. It was weird. And very controversial. The topic of sexual abuse got so heated, Global Road Entertainment pulled the film from theatres and put out a new cut with the scene removed.

While a kids movie should, in all good sense, run far away from the topic of unconsented sexual touching, genital examinations are also a natural part of show dog competitions. I use ‘natural’ loosely because Fixed finds a more appropriate and comedic angle to send up this very unnatural treatment of dogs. It gets particularly pointed with the subject of pure breeding, which gets compared to eugenics and in-bred monarchies.

As obnoxious as its comedy can get at times, Fixed uses the R-rated setup to address the obscene ways dogs are treated. Domestication is one thing, but materialism is another, a state of mind that has caused many dogs to become accessories for visual consumption (one pup’s obsessed with his Instagram following, another’s imprisoned in a handbag).

Fixed takes a crass route to successfully show how the traits of dogs we look away from are completely normal states of being—especially their sex drives—while the environments people put them through for the sake of status and attention-seeking are innately grotesque.

Tartakovsky could have said all this in a serious way, but that hasn’t gone down well in the past. Martin Rosen, director of beloved classic Watership Down, found this out the hard way with his second Richard Adams adaptation—1982’s The Plague Dogs. This beautifully bleak masterpiece targets the cruelty of animal testing facilities, following two escaped dogs as they attempt to outrun authorities who believe the pair carry the bubonic plague.

Never heard of it? That’s understandable. The film performed terribly in theatres, with audiences reportedly deterred from the depressing subject matter. This didn’t seem to be a problem when it was rabbits fighting for their lives in Watership Down. But dogs? That was a barrier Rosen didn’t see coming. He apparently got physically hit by an elderly audience member who asked him,” How could you do that to those dogs?”

This heightened sensitivity to the plight of puppers reflects general audiences’ preference to see dogs as doggos—sweet, innocent, naïve. It’s so prominent, we’ve now got film trailers guaranteeing the dog will live, from romance survival dramas to Nazi-killing action flicks.

It’s heartening, in a way, that we collectively care so deeply about these animals. But to see them as only cutesy cuddle bears while looking away from everything else that so obviously defines the animal isn’t an act of affection—it’s an act of ignorance that prevents us from appreciating them completely. In his own crass way, Tartakovsky takes that ignorance and, like a domesticated dog who’s just shat on the floor, rubs our noses in it. How else are we going to learn?