Season two confirms Fallout as one of the greatest shows of right now

Arguably it’s the best video game adaptation ever made (if you want to pick that fight with The Last of Us).

The house always wins. Yet, Fallout’s second season would like to ask you a follow-up question: do you know who, exactly, the house is? Who’s really been raking in all your chips? Fans of the post-apocalyptic game series nearly lost their heads last year when a final shot reveal of a certain, American skyline seemed to confirm that season two of the show would be bringing in elements from New Vegas, ie the best Fallout game, according to popular consensus.

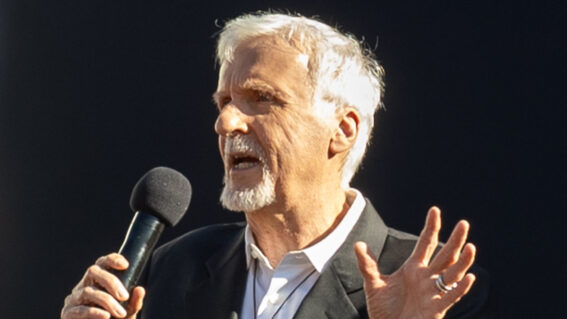

In the source material, players encounter, via computer screen, a Howard Hughes-ian oligarch in control of the city. He’s named, conveniently, Mr. House (and voiced by the late René Auberjonois). This season, he’s played by Justin Theroux with a penny dreadful moustache and a debonair turn of phrase. In season one, he was portrayed by Rafi Silver. I’ll let the show explain how that works out.

Mr. House, in the game, is the shadow hand shuffling pawns across the board. He has a disdain for petty humanity and a mathematical attachment to precision and control. The same is true here—except, and I must be careful about how I phrase this, as the narrative turns here are truly quite spectacular to discover, showrunners Graham Wagner and Geneva Robertson-Dworet have allowed a pipette’s worth of ambiguity and doubt to invade Mr. House’s story. And that changes everything. It’s doubt that cements Fallout as one of the greatest shows on television right now, and arguably the best video game adaptation ever made (if you want to pick that fight with The Last of Us).

Their adaptation hasn’t explained the magic away. It hasn’t narrowed the games’s scope with definitive answers. In at least the first six episodes given to critics, it hasn’t enforced a canon ending on New Vegas (which allows players to determine the future of the Mojave Wasteland by siding with one of four factions). Instead, it’s selective about what it does reveal, and in doing so, asks brand new questions that could potentially bust the doors wide open for both the future of the show and the games. It enriches where other adaptations enforce limitations.

Season two is, in short, about the divisions within the divisions. In a world this broken, with resources this much a scarcity, people turn on each other again and again until the survivors end up as fundamentally lonely and bitter as our beloved Ghoul (Walton Goggins). It’s a smarter, more nuanced way to engage with the divisiveness of the moment, because Fallout never preaches that people should reach across the aisle and shake hands with the people who fundamentally hate them.

Instead, it sympathises with the struggle of not knowing who to trust, and in that struggle, coming to trust no one. It’s there in the dynamic between the Ghoul and Lucy MacLean (Ella Purnell), the 200-year-old irradiated cowboy who’s come to see goodness as weakness, and the naïf fresh out the vault, where the privileged waited out the nuclear war in relative suburban comfort. That Lucy’s “okie-dokie”ness would be tested out in the Wasteland is a given, but season two lets her relationship with the Ghoul breathe a little, so that we’re allowed to see, too, what’s brought this strange man to the brink of hopelessness (and Goggins really shines here, projecting incredible pain from out behind god knows how many prosthetics).

Yet, my favourite in the series has always been Maximus (Aaron Moten), who represents something between Lucy and the Ghoul’s moral extremes (and I don’t mean between good and bad, but between believing such a strict binary exists and seeing absolutely no difference between the two).

Executive producer Jonathan Nolan has repeatedly described Maximus as the stand-in for the average Fallout player. He’s us, the people who want to do good in a world where the path to good is anything but clear, who have to reckon with the values we’ve inherited and test them for their veracity. Maximus, after his entire life in Shandy Sands was wiped off the map, was raised by the religious military cult of the Brotherhood of Steel. And now we’ve seen him fall back under their influence, after he’s had a taste of what the outside world can be like and even what it’s like to fall in love.

That’s what makes Fallout so faithful to the games. Because as much as I can sit here and praise the vast, exhaustive level of referential detail put into this thing—and season two goes out of its way to introduce so many of the game’s core mechanics and features in a way that will delight fans and feel like clever world building to the uninitiated—it ultimately triumphs because it understands what these games are trying to stir within us. The first victim of the end of the world is certainty.