Retrospective: warm up for the Australian Open with brilliant sports doco In the Realm of Perfection

At the 1984 French Open, legendary tennis ace John McEnroe almost experienced perfection. Eliza Janssen recommends an intellectually provocative 2018 documentary about this moment in time, if you’re really feeling this year’s Australian Open drama.

As you take in the serves, rallies, and annoying shrieks of this year’s Australian Open—and perhaps even the newest season of Netflix’s docuseries Break Point—consider the court as a canvas for cinema. As with boxing, the sport’s one-on-one intensity means it can hone in acutely on each player’s expressions, personalities, all within an environment that’s already perfectly framed up for physical and emotional choreography.

You could watch plenty of tennis docos and scripted stuff while you’re feeling this vibe, including 2022’s simply-titled McEnroe portrait. But I strongly advise that you instead seek out the 2018 documentary John McEnroe: In The Realm of Perfection. Directed by Institut national du sport historian and filmmaker Julien Faraut, it’s got all the soaring athletic highs and devastating lows of any good sport movie, plus clever film school flourishes. What emerges is a provocative synthesis of the formal boundaries of athletic and cinematic art. The big personality at the doco’s centre doesn’t hurt its sense of drama, neither.

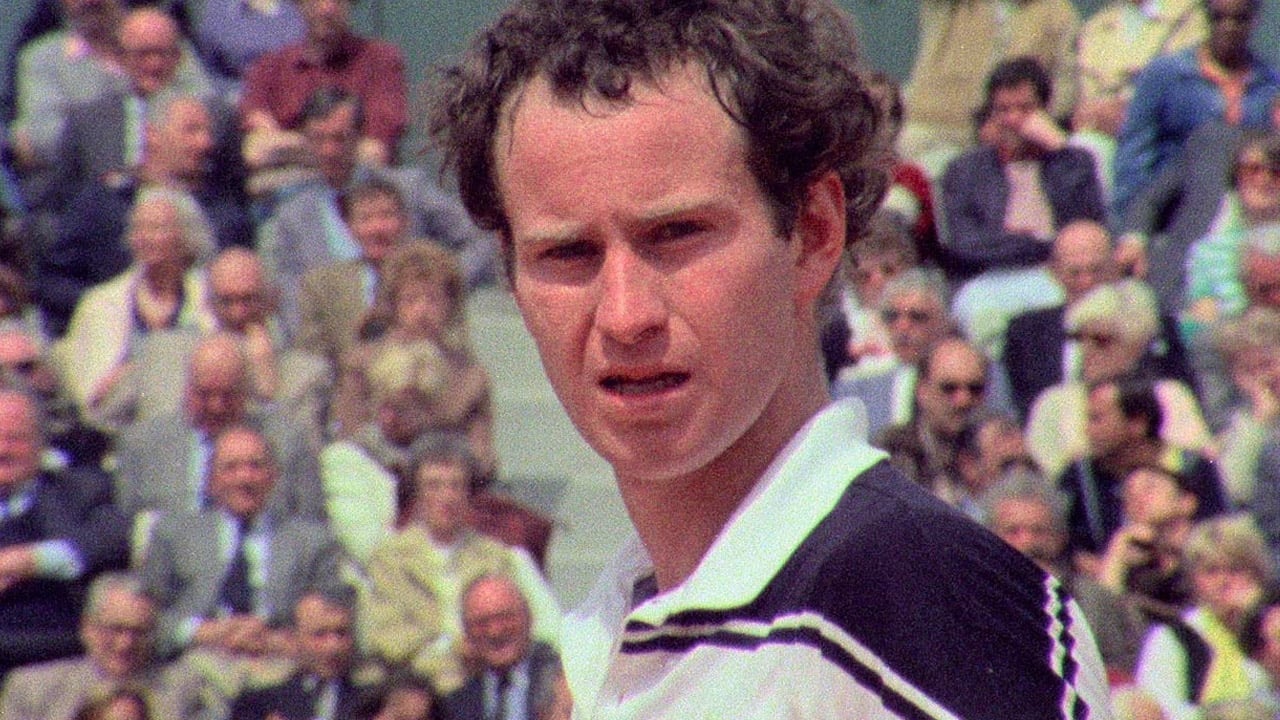

A quote from Jean-Luc Godard sets us off on the right track (“Cinema lies—sport doesn’t”), before Faraut explains just what made McEnroe such a compelling anti-hero of the clay court. His tricks include glorious slo-mo and a skeletonised graphic of the player’s serve, McEnroe’s genius lying in his deceptive gesture: for his opponents, “when his movement gave away his intention, it was already too late.” The curly-haired American is hailed as a master of time, the most pivotal element to both tennis and cinema in general. “McEnroe is not a filmmaker, but he excels in the area of inventing time, thanks to his dexterity”, Matthieu Amalric’s coolly narrates: “it is he who dictates…he who says ‘cut’”.

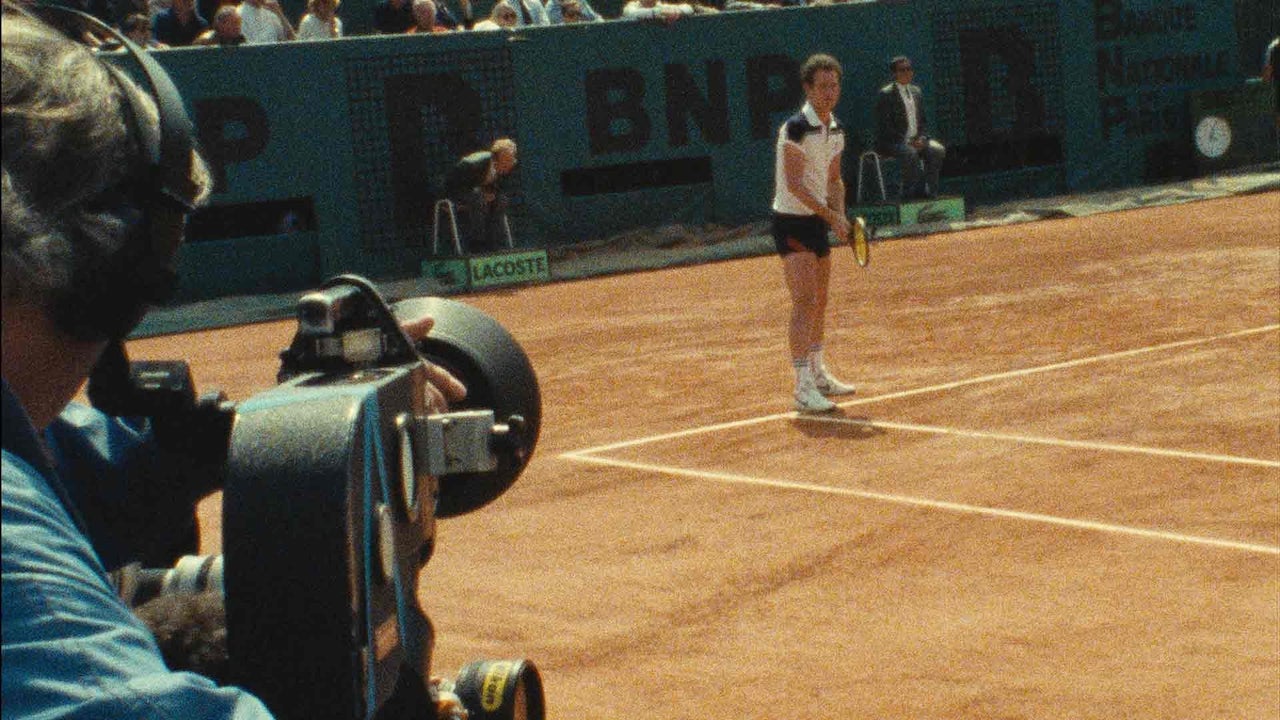

In this way, In The Realm of Perfection becomes a documentary about a bossy director—the subject as auteur. Faraut is relegated to a master editor, working from forgotten footage that France’s first national director of tennis Gil de Kermadec captured during the 1984 French Open. The images are grainy, with our true director—the ruthlessly ambitious McEnroe—stranded alone between the rust-coloured court and bright teal advertisements closing him in on all sides. De Kermadec and his sound guy had front-row seats to every incredible ace shot, and, most entertainingly, every one of McEnroe’s classic tantrums.

Faraut playfully contrasts the tennis world enfant terrible’s bratty public perception to clips from Raging Bull and Amadeus, but the guy comes off pretty good in general. Our close-up insight to his playing style means we don’t often get a look at his opponents, or any thrilling rallies between both players. “It’s as if he’s playing himself”, the director remarks. Until the camera—and thus we, the thrilled spectator—is drawn directly into the drama. This is a documentary that’s fully aware of the camera’s intrusive, transformative presence, the impossibility of true subjectivity. One hair-raising shot has McEnroe locking eyes with us, through the decades and graininess of de Kermadec’s fly-on-the-wall footage, before complaining to the umpire about the oppressive presence of photographers.

In The Realm of Perfection concludes as a tragedy, the possibility of an absolutely perfect season of tennis slipping just out of McEnroe’s sweaty grasp. By the end of the film, one feels pretty sympathetic to the shouty lil guy: “a man who played on the edge of his senses”, narration generously excuses, “he was capable of reacting to the tiniest change in noise or atmosphere.” Have we spectators ruined the star’s ambitions, or did he psych himself out—a case of a self-sabotaging, control-freak director overthinking his moment of glory?

When Ivan Lendl is handed that final, French Open-scoring shot, McEnroe stands alone, hands on his hips. He’s civil enough to shake Lendl’s hand, and the umpire’s, then he sits alone. Nobody races forward to give him a kind word or a pat on the back. When TV cameras rush forward to capture his pure, perfectionist fury at himself, he flaps his racquet at them. Once you’ve seen In The Realm of Perfection, you might just cheer those angry swings on: it’s not often in cinema, nor in sport, that we get such a close glimpse at that impossible realm. You’d be mad, too.