There’s never been a better time to fall in love with short films

Liam Maguren highlights some of the recent big releases in the short film universe and chats to filmmaker Anna Duckworth (Just Kidding, I Actually Love You) about the current state of short filmmaking.

Loving short films used to be niche. Often falsely seen as the domain of pretentious artists, or the practice space for filmmakers hoping to make “proper” films, short films have never been taken seriously as a mainstream art form.

It didn’t help that short films used to be hard to find. You might have caught a handful at a film festival or had one spring up on the Rialto Channel, but aside from those small outlets, it was nearly impossible to make a habit—and, therefore, love—out of it.

But the year is 2023, and things have changed a lot.

Somehow, on our tiny but mighty island nation of Aotearoa New Zealand, we’re about to see the big-screen release of a 31-minute Western that has no relation to the country’s biggest short film festival, which is also about to dawn on cinemas nationwide. We’ve also just seen one of the world’s biggest filmmakers casually drop four short films on Netflix, Disney platforming a group of emerging filmmakers through their short film initiative, and Shudder’s about to unleash another collection of horror shorts as part of an enduring found footage anthology series.

There’s never been a better time to fall in love with short films. Here’s where you can start:

Show Me Shorts

For 18 years, the renowned short film festival has been spreading the good word of tiny cinema in all its varied glory. Showcasing homegrown talent and an eclectic selection of international filmmakers, the team at SMS has always been about programming a festival for everyone.

This year’s no different. Spread over 10 sections, the 2023 big-screen offering traverses many genres—from the whānau-friendly to the taboo-ticklers. For the indecisive, The Sampler gives audiences the best taste of what Show Me Shorts is all about with a handpicked selection of some of their best short films on offer.

One of those films is Just Kidding, I Actually Love You (pictured above), a crowdfunded New Zealand film nominated by Show Me Shorts for Best Screenplay (read the full list of nominees). I somewhat cruelly asked the film’s director and co-writer, Anna Duckworth, to describe her film in exactly seven words: “Realising you are the asshole, and changing.” The film stars recent Billy T nominee Rhiannon McCall as a woman with a poorly devised plan to woo her ex by breaking into his home and doing a romantic gesture that may or may not involve this song.

Duckworth has well over a decade of filmmaking experience having featured as part of NZ’s Best in the Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival with Pain, made waves with renowned web series PSUSY, and directed numerous winners and finalists in the country’s biggest filmmaking competition 48hours. She told me more about her journey making films and provided me with insider knowledge about the current short film landscape.

“I grew up in a family where we weren’t that good at talking about our emotions or hard things, and the way we would diffuse that was by making a joke. So I feel like that has evolved into my directorial voice—looking at difficult things and making people laugh, just cut the tension so people can relax a little bit, take the seriousness out of something.

“We also use humour a lot to talk about things in an approachable way. Pain, for example, I was trying to talk about this earnest, sincere thing of realising your parents are not superhuman, they’re fallible. I’m a parent, I’m not perfect, and my kids are gonna realise one day that I’m just like them, and they don’t know what they’re doing, either. But then putting a few laughs in there, or a few shocking moments, that’s definitely part of my style.”

I then asked about the appeal of short filmmaking: “It’s such a mixed bag. You can make a short film in a weekend, or you can make a short film over like six years. As an emerging filmmaker, the challenge that you set yourself, of being able to tell a complete story, within a short timeframe is really important before you move on to anything longer. If you can’t tell a complete story in six minutes, what are you gonna do with 90 minutes? I think it’s about getting succinct.”

We also see the reverse happening: renowned feature filmmakers jumping back into the short film ring to tell more succinct stories. That leads us to…

Strange Way of Life

Pedro Pascal and Ethan Hawke lead this 31-minute-long Western from Oscar-winning Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar (The Skin I Live In, Parallel Mothers) as star-crossed lovers reunited 25 years later. Jake (Hawke), now a Sheriff, is dumbstruck to see Silva (Pascal) ride into his sleepy town. The pair’s reunion seemingly goes as well as they both could have hoped, but that sweetness turns bitter very quickly when Silva reveals the true reason behind his appearance.

There’s no denying the duo’s chemistry—the unrestrained joy that sparks in Hawke’s eyes when Silva first shows up, the desperate longing so readable on Pascal’s face. The performances make the picture, though Almodóvar admirably mimics a bunch of filmmaking techniques to make the film feel like a Western from the 1950s. Valient still is the fact that, while this is a queer love story with a significant element of tragedy, the story isn’t the eye-rolling queer tragedy one might brace for when entering a period piece about two gay cowboys, ending on a vaguely hopeful note.

In a bold and exciting move, Sony is opening this short film in select cinemas like any other film—albeit with cheaper ticket prices. I’ve been doing this job for over a decade and this is the first time I’ve laid eyes on such a release in this country. It’ll be interesting to see how this performs, what this could mean for the future of short film cinema distribution, and observe audiences react to a film ending at a time earlier than they’re used to.

“I think a lot of mainstream audiences aren’t familiar with short films as a medium,” Duckworth mentioned. “So we do get some people being like, ‘This is amazing, where’s the rest of it?’ They’re not familiar with the format.”

I asked Duckworth her take on the little-known world of short film marketing: “It was interesting with Pain, I got an Italian distribution company, and their whole business is distributing short films. It’s crazy, in New Zealand, to imagine that someone could make their money doing that—it seems like we have such a small industry. But in Europe, especially, there are people whose whole career is short films. I think in New Zealand, we view it as a stepping stone towards something bigger, whereas for some people, that’s their whole world. It’s an art form, in and of itself.”

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar

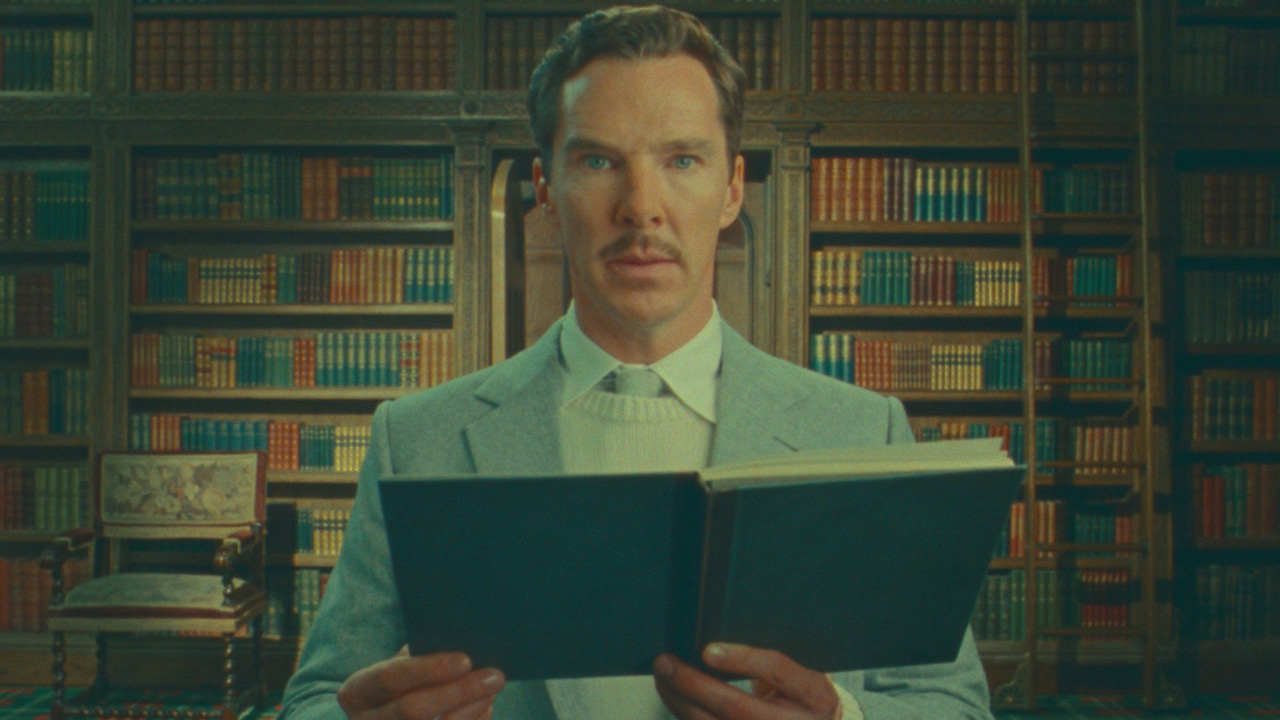

Beloved auteur Wes Anderson seems to know the artistic value of short films more than anyone, having regularly dipped in and out of his feature filmmaking to do the odd short. Most recently, he’s written and directed four adaptations of Roald Dahl short stories for Netflix. The first, longest, and arguably best of the lot is The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar.

Benedict Cumberbatch plays the titular Henry Sugar with all the fast-talking, unblinking, straight-spined verve inherent to Anderson’s style. Told with a Matryoshka doll-like narrative similar to The Grand Budapest Hotel, the story revolves around the disgustingly wealthy Sugar’s quest to derive meaning from his privileged life. Believing he’ll fill that hole by learning another culture’s mind-enhancing abilities and using those skills to gamble, his journey soon leads him to a far greater epiphany.

It really is a wonderful story, made even more memorable by Anderson’s specific approach here. Every key character narrates the story while simultaneously in the story, with set elements changing in and out during the performances. It’s a stageplay on steroids, monologues on molly, and just a damn fine film to behold.

Henry Sugar clocks in just shy of 40 minutes while Anderson’s other three Dahls—The Swan, The Rat Catcher & Poison—each run at a palatable 17 minutes each. Together, all four would run at the tidy time of an hour and a half, but Anderson/Netflix avoided Frenching that dispatch, instead allowing each entry to stand as a whole short film rather than being part of a feature.

Talking to Duckworth, I asked what short films can do that features cannot: “The diversity that you can have within short film. It’s so hard to get the resources to make a full feature, whereas it’s much more achievable for filmmakers to make short films, so you can have so many nuanced stories from so many different walks of life. I would love for those filmmakers to be given the money and resources to make features, but I can understand that we can’t all be feature filmmakers straightaway.”

Disney’s Launchpad: Season 2

Over at Disney+, the Launchpad collection of live-action short films platform up-and-coming filmmakers from minority backgrounds. Though Disney has been often accused of using the word ‘Diversity’ like a sale sticker, Launchpad is a genuine win for the short film format, telling a wide array of cultural experiences targeted towards a mainstream audience.

Collection Two just came out and includes the film Beautiful, FL, a story about a teen girl who hopes her Puerto Rican treats can win her a big ice cream competition. Black Belts follows a Compton kid looking to prove himself at an underground dojo, only to receive a big lesson in manhood. In The Ghost, two young sisters must contend with an otherworldly entity that awakens after a dinner table fight. Set during the Hungry Ghost Festival, Maxine centres on a young woman seeking paranormal advice about introducing her new girlfriend to her family. Project CC follows a cloning experiment gone awry. And The Roof tells the story of a Northern Cheyenne teen who discovers a connection to his family he thought was impossible.

When chatting about the nature of platforming Aotearoa short films, Duckworth mentioned a local initiative similar to Disney’s Launchpad: “In terms of actually getting your film seen in New Zealand, there’s NZIFF, Show Me Shorts, Māoriland and other film festivals. And then you’ve got Someday Stories which puts them straight online and on social media, which I think is quite a nice way to do that—not like, buried deep in someone’s on-demand video service.”

Having just released its seventh series, Someday Stories champions young local filmmakers telling stories focused on sustainability. The initiative came up when I asked Duckworth about the last great short she’d watched—to which she replied with the Someday Stories doco I Stand for Consent. “It conveyed a lot in a short space of time. And just stylistically it had a really strong look. I thought it was a really strong documentary.”

V/H/S/85

It wouldn’t be fair to write about short films without mentioning feature anthologies. While technically not short films, they nonetheless champion the format and their previously-mentioned ability to bring diverse experiences to the screen.

Seems silly to relay that sentiment to V/H/S, found footage horror anthology franchise, but the series found a second wind once Shudder took it on and they started labelling their entries by year. Previous entries V/H/S/94 and V/H/S/99 placed big voices like Timo Tjahjanto (The Night Comes for Us) and Flying Lotus (Kuso) alongside emerging filmmakers to continue collecting a vast array of horror experiences.

Releasing this week, V/H/S/85 leans a little heavier on experienced horror directors with Scott Derrickson (The Black Phone), Gigi Saul Guerrero (Bingo Hell), Mike P Nelson (2021’s Wrong Turn), Natasha Kermani (2020’s Lucky), and David Bruckner (The Night House) each making their own tapes for this proverbial box set. If it’s anything like the previous two entries, we can expect more inventive—and straight-up odd—horror ideas that probably wouldn’t last a feature-length amount of someone’s attention, but could very well hit as a shotgun blast of short cinema.

Sometimes, that brief hit is exactly what we need, and short films can provide it. “This is a fast-paced world,” Duckworth told me, “people don’t have as much time to dedicate to watching content as they would like. Being able to make someone feel something in a short frame of time, it’s really impressive.”