TOITŪ Visual Sovereignty: how a film about Māori art became a story of resilience

Chelsea Winstanley’s latest feature isn’t just a celebration of Māori art but also a compelling microcosm of contemporary colonialism at work.

Chelsea Winstanley’s TOITŪ Visual Sovereignty returns from its World Premiere at NZIFF for a nationwide cinema run with special special screenings and discount tickets. We learn more about how this film started, the moment that changed the story, and how patience saved the ending.

Oscar-nominated filmmaker Chelsea Winstanley (Jojo Rabbit, Waru) first heard about the idea for Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art back in 2018. Catching up with curator Nigel Borell, a simple chat would kick-start a seven-year journey making TOITŪ Visual Sovereignty—a film intended to capture the creation of the largest Māori art exhibition in New Zealand’s history, but would end up telling a bigger and more profound story of cultural resilience and authorship.

Winstanley told Flicks in more detail: “[Nigel] started telling me he was pulling together this incredible exhibition and how it was kind of like the next iteration of Te Māori, which was more about the traditional arts, but [Toi Tū Toi Ora] was really dealing with the contemporary space. I was like, ‘Oh my god, someone’s got to be documenting this because it sounds just too epic.’ And he said, ‘Oh, well, do you want to do it?’”

A Zoom call at the end of 2019 sealed the deal. Borell pitched the idea, the Auckland Art Gallery backed them, and Winstanley jumped on the project. Even the lack of money didn’t phase her: “I just think if you have the passion and the drive to do something, let the other stuff follow.”

With a colossal task in front of him involving over 100 artists and more than 300 artworks, Borell was a natural pou to build the film around. Winstanley thought, “Oh my God, how on earth do you put something like that together? I thought it’d be really fascinating to see. Pretty much the entire gallery is working on this one thing. I just I love that kind of communal support and that relationship that he had with Haerewa (the gallery’s Māori advisory group). I think that speaks to him as not only an artist, but someone who really loves that tuakana teina—the relationship, the guidance your elders provide.”

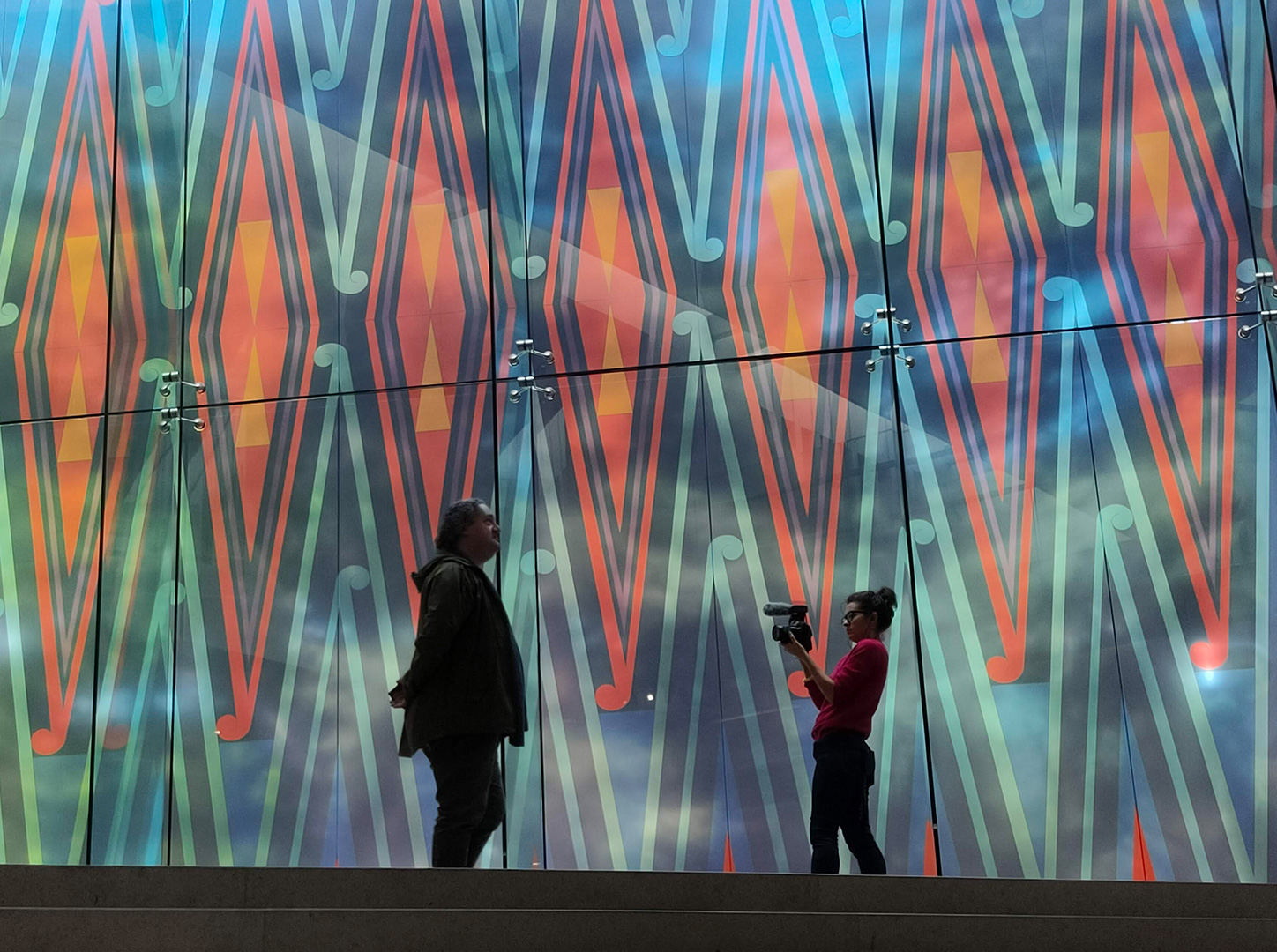

Troy Kingi watching the work of Ngahina Hohaia

Winstanley was given full access and hit the ground running. “They gave me a desk at the gallery. I could only afford to have a proper crew at certain points. Other times, it was just me. Luckily my dear friend Mikey Jonathan gave me one of his cameras. At times, I just had my bloody iPhone, whatever I could get my hands on trying to capture as much as I could up until the opening.”

But before Toi Tū Toi Ora launched, the story took a significant turn when Borell stepped down. Pivotal to this were mounting concerns about Kirsten Lacy, the Auckland Art Gallery director at the time who initially appeared open and willing to stand alongside Borell and the team only to later assert institutional (see: colonial) control over the exhibition. These revelations play out in the film over a series of Zoom hui—some show subtle cracks forming in the group relationship, others show shocking inabilities to read the virtual room.

Chelsea Winstanley and Darryl Ward

Chelsea Winstanley

“It was pretty obvious that the film was going to take a different turn,” Winstanley recalls of the whole ordeal. “It takes a pretty brave person, and someone without a shit-tonne of ego, [to make] that move… a bigger decision to benefit a lot more people than himself, which I think is quite commendable.”

Commendable as it was, Winstanley didn’t want to end the film on “this weird, deflated feeling. I remember having a cut [of the film] months after… it just didn’t feel right.”

This is where the low budget and independent spirit turned into a blessing. “The great thing about self-funding is that I didn’t have to be answerable to anybody or anybody’s expectation. I’m so grateful that a lot of the artists just trusted me. I’m sure a few of them probably thought I was never going to bloody finish the thing.”

Shane Cotton

After a six month showing at the Auckland Art Gallery, Toi Tū Toi Ora came down in May 2021. That’s four years before the film would ultimately debut at Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival. “But I just knew deep inside, I couldn’t finish it on that. There’s got to be something else. It’s in the title, that word TOITŪ means to be permanent and to be enduring. Something told me to wait.”

At the end of 2023, Winstanley’s patience would pay off in spades. “That’s when I got little whispers that there’s an unprecedented number of Māori artists curated in the actual Venice Biennale, not just having a New Zealand pavilion, but actually curated.” We talked a little more about the ending, which won’t be spoiled here, but it felt like the celebratory conclusion Winstanley was looking for.

Hemi McGregor

It also proved to be the ultimate validation for Borell, whose resignation blew up in the media. “It probably sounded like he spat the dummy and just left or something. And no one really knew, apart from him, what he truly had gone through.”

Until now. TOITŪ Visual Sovereignty opens in select cinemas across the motu from 13 November, with $10 tickets at Silky Otter Cinemas as well as gallery screenings in collaboration with The Govett (Taranaki), The Dowse (Pōneke Wellington), Souter (Nelson), and Te Atamira (Queenstown), with more arts organisations and curators joining the kaupapa. For more information about screenings, private bookings, Q&A opportunities, and to purchase official TOITŪ: Visual Sovereignty merch to support local indie filmmaking, visit www.toitufilm.nz.