Martin Phillipps on Chills doco: “There’s been a lot of tears shed, I’ll tell you”

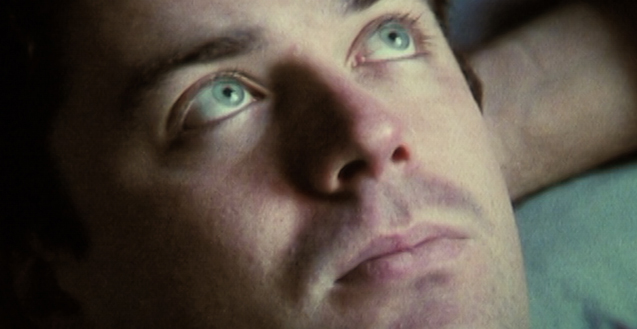

“To know that they might be filming me dying was actually pretty heavy.”

Releasing in cinemas during NZ Music Month, a new documentary recounts the extreme highs and lows of iconic Kiwi band The Chills, and the band’s creative mastermind, Martin Phillipps.

The Chills: The Triumph and Tragedy of Martin Phillipps had its world premiere at this year’s SXSW film festival in Austin, Texas (Dominic Corry was there to speak with director Julia Parnell), and New Zealand audiences will be able to see it from May 2.

Flicks editor Steve Newall caught up with Martin Phillipps for a lengthy chat about being the subject of the documentary (while undergoing a massive health scare, no less) and what’s going on with The Chills today.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

FLICKS: I think anyone that sees the film can’t help but think we’re lucky to still have you, really. How’s this year been for you so far?

MARTIN PHILLIPPS: It’s been a bit of a roller coaster but also kind of a relief to see the completion of the documentary. And of course, that coincided with the dramatic news in my personal life which is covered in the documentary, so it suddenly became a completely different deal and a much bigger, I guess, project overall. So it’s been very personal stuff for a long time and having to kind of repeat things, open up old wounds repeatedly.

It’s been good to confront certain issues and to actually learn, finally, what some of the rumours and sort of gaps between people have been about because I think, as you see with the documentary, the lack of communication was one of the worst parts of the whole story. So to be able to address some of those has been really good.

But also, I gave the go-ahead to the documentary basically saying that I wasn’t going to interfere with anybody else’s memories of it—I didn’t think that was fair, that’s not my role—and people who’ve their own reasons and recollections of what happened, but that I would, at least, have the right to point out if things were factually inaccurate. And that really only happened a couple of times. So there were things I disagreed with about some other people’s points of view about what happened, but in terms of sort of a documentary narrative, it was important to leave those in anyway.

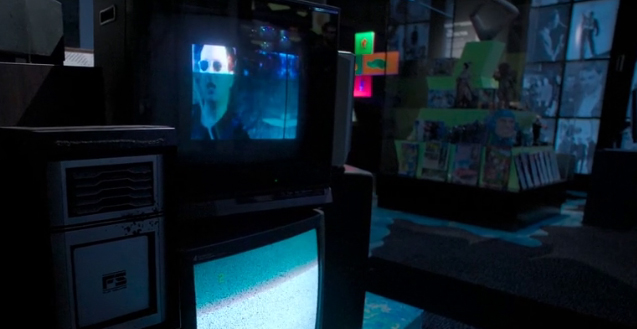

I’m guessing that as well as perhaps an ethical decision about people being able to say what they want, your film collection seen in the doco suggests you know what makes a good documentary.

I think I had a rough grasp on it, but I’ve certainly watched more rockumentaries in the last couple of years than I ever have in my life. I probably watched 30 or 40 of them, and I saw the same mistakes being repeated again and again and realised that, really, to be blatantly honest as much as possible was kind of the only way to go. And Julia, the director, and I had to learn to really trust each other.

And there were other aspects. The whole Hepatitis C thing [Phillipps’ health complications with the disease figure prominently] became kind of crucial. If I wasn’t prepared to talk about that publicly, then that was probably hypocritical because it’s something I went on about, the fact that it shouldn’t be as stigmatised as it is. It’s just another disease. And so that whole narrative got sort of interwoven as well, and there’s no way of keeping that separate from some of the disastrous mistakes I’ve made in the past.

Does it create any practical obstacles for you now touring internationally? Obviously, you’re in a position where you can disclose and talk about it because it’s not ongoing. But now that your Hep C’s been treated, does that make it a lot easier to travel, or were there barriers in place because of it?

The main barrier with the Hep C itself was just lack of energy, and the recent American tour was the longest string of gigs I’ve done probably since the ’90s. So there was about 22 shows, I think, all up.

And what I’m learning now is even though the virus itself has been halted in its tracks from causing further damage, my medical support and I are assessing what the long-term damage of it is, because it mentions in the documentary I’ve only got 20% of my liver still functioning, and that’s not going to get better. It may get a tiny bit better which was one the unexpected side effects of these new treatments – my liver actually has been repairing itself a bit—but it’ll never disentangle all that fibre.

So while my energy levels are so much better than they were, I still just crash most afternoons. I was describing to somebody it’s not just like, as I’ve been told, “Oh, everyone gets tired at work, and everyone would love a snooze. You’re just able to.” I’m talking about if I was driving a car, I would definitely pull over. It’s a dangerous time.

So I’m probably stuck with that forever, I suspect, plus its also 20 years of that disease, and I’m 55 now, so I don’t know what I would normally be like at this point. But what you’re talking about, sort of the legality of it in terms of getting working visas, it’s still problematic, even just the reputation that you’ve once been a drug user of any sort, and obviously, in particular, the United States, but now even the UK is sort of getting, and Canada surprisingly, pretty much tighter on just any hint of you having been a wayward teen.

What did you do to get ready to hit the ground running for a 22-show run in the States as opposed to, “We’re going to do Auckland and Wellington this weekend, and next weekend, we’re going to Christchurch and Dunedin”?

Well, I guess that was actually part of the process. The New Zealand tour last year was split over four long weekends, and that was seeing if I could handle that sort of three or four shows in a row, a definite day off (which means not a travel day), keeping an eye on my voice, in particular.

I discovered Throat Coat tea by Traditional Medicinals which came highly recommended in the States, and I think you can actually get it some places in New Zealand. That saved the day for me because that’s been the main worry.

I’m stuck with songs that I wrote not knowing anything about key changes when I was young, like Heavenly Pop Hit—at the top of my range. Basically, holding that one bloody note all the way through the song is just a disaster. And that’s not the only one. So to get through that many shows was just like, “Yes. That’s enough.”

I mean, we can function on that as a working international band, and that’s good. And it’s interesting looking back at old interviews, as obviously I’ve had to for the documentary, and seeing me just blithely talking about, “Oh, yeah. We’ve got 100 shows between now and the end of the year.” And that’s just how it was back in the ’80s. We did hundreds and hundreds of shows. So I’m in, a lot of ways, quite “a fortunate position” now to be able to pick and choose just a bit more carefully.

The film could easily have been an epitaph, but now you’re as active as you’ve been for a long time if not more so. When you were in the U.S. did you sense it was reigniting interest in the band?

Well, it has become a kind of a celebration of our history and the resurgence of interest in the band has been a genuine wave, even before people knew about what was going on behind the scenes or knew about the documentary. It’s lucky I’ve got a good dark sense of humour because, at one point, I did have to sign off on the two possible scripts for the movie, the good ending where Martin recovers and the not so good ending. And that was kind of weird.

That’s a very strange piece of paperwork.

Yeah. To know that they might be filming me dying was actually pretty heavy. They caught me at a good time from a dramatic point of view. But the level of interest in The Chills, there’s almost a kind of a weird zeitgeist about it, particularly in America. What we’re singing about, the way we’re singing about it, the topics covered in kind of a melodic but strong form seem to be really registering at the moment with those who came along from our age group but also a whole lot of younger people coming along.

And I’m starting to realise it’s not a million miles away from some of the bands they’re listening to who are quoting us as an influence. So that’s a window of opportunity, and I know it won’t last forever, but it’s just very interesting timing.

You seem like someone who’s quite aware of where your material and where your records sit in the musical firmament. Do you consider that when you look at your legacy of records you’ve made, the songs you’ve written?

I think I certainly did have a good grasp on that. Now I don’t listen to as much music as I should because, for a long time, I was just hearing repetition and then started being aware that, in fact, there’s probably more amazing music being made now than ever before and extraordinary combinations of the sort of cultural kind of cross-pollination going on. So I’ve got a lot of catching up to do, and I don’t really know where we stand amongst some of that, except—dare I say it?— there’s an integrity to what we do which people do relate to, I think. Yeah. You’re not really allowed to say that about yourself, but it’s kind of true.

We’re pretty honest about we’re trying to accomplish and how far we’re prepared to market ourselves to do it. And I think that seems to go down well with certain people, and it means we’ll never reach sort of a mass audience. But having said that, I’ve got ideas and with Silver Bullets and then Snow Bound, it has been a deliberate stepping up of using the studio to kind of bring The Chills up to where I think we should be now, and the next album is where I really want to start actually competing with what’s going on around us and finding The Chills thing within that.

So whether I manage to pull that off… I’m sure I say that before every album, but I’ve got some more solid ideas and the right people around me to maybe really start getting a bit more adventurous, which would be good.

Not to put the mockers on that, but one of the many things that stood out in the doco is that really terrible studio experience that’s recounted where you’re very much being shoehorned by a US label producer. When things go wrong in that environment, how bad is it? What’s the reality of being in the middle of that process and realising what’s happening?

I will say that the Soft Bomb album recording experience, for the purposes of the movie, is made to seem a wee bit darker that than it was overall. In some of the interviews for that, I also pointed out it was probably one of the biggest learning curves I ever had in terms of dealing with the studio, working under pressure, solving musical problems. But the downside of being kind of an indie band, even given the luxury of kind of a Warner Bros. budget, was that we never had the opportunity to say, “This is not working. Let’s scrap this. Let’s start again.”

You’re realising you’re going to have to make this work, and it could even be detrimental to your career, releasing this record, but you’ve really got no choice. And so that was the saddest thing about it. Although, certainly with hindsight, there’s at least half a dozen really excellent songs on that record, and it took people a long time to discover that, and even more so with Sunburnt that came afterward because that was so not what was happening musically at the time by the mid-’90s.

And it’s kind of like Chills fans who got ultimately sick of ending up listening to Submarine Bells, again and again, would decide to check out the later ones and found, to their surprise, there’s actually some good music on there. But that’s the main thing is we’ve never had that luxury of being able to say, “No. Let’s just scrap that and move to another studio, get another producer, and start again.”

It’s high emotion because that’s what you’re having to draw on. And it’s a skill which I think I’ve only been a lot better at the last two albums is learning that you have to project [vocally] another 30% for it to even sound like you’re delivering at a regular level, both live but in the studio as well. What I would have used to have called acting and being fake, I now realise is actually an integral skill to the whole getting this music across to people and really sort of drawing on something deeper.

You’re drawing on big powerful emotions. If you’ve been writing about events in your life, you’re having to reawaken those, and then you suddenly need to shut that off and walk back into the studio to have a listen to the playback. So of course, there’s extraordinary energy, and little blow-ups and things happen. But we’ve never had people kind of hit each other or storm out of a studio or… I was about to say throw a bottle against a wall. I don’t think it’s happened, but it’s been pretty close.

It’s interesting that you just mentioned the idea of acting and authenticity and vocal performance. It just shows how important that must be to you if that’s something you’d consider.

Well, it’s a big change. I mean, coming from the very low-key and “honest delivery” of the Dunedin sound, even to be sort of seen to be kind of trying to put on a show, you were selling out, with the notable exception obviously, strange enough, of Chris Knox, who kind of started it all, who was a natural show person. And Shayne Carter had the kind of charisma to do that as well. But the rest of us, it was all very kind of humble and very kind of, “We speak to you through our songs, and we mumble in between”.

It took me years to realise that, in fact, no, there’s more to it than that. In fact, most of the bands we loved would put on this great dynamic show, and that’s the kind of irony of it. Most of the artists we listened to were people who had fought really hard to get where they were and would go to great lengths, and possibly weren’t very nice people at all. And here we were with the luxury of sitting in a comfortable little Dunedin on unemployment benefits just making music when we felt like.

So I don’t know. I just feel more obligated now to try and connect with people who never otherwise would be exposed to anything like my kind of music, the kind of stuff I love. And I’m getting better at it, and it’s working.

Alongside the retrospective elements of the film about your career, and alongside your health, is this other narrative around the exhibition that’s being prepared as you mine through your massive collection of stuff at home. I started thinking about what your relationship to all those objects is like and what the positive and negative elements are. Do those objects have a hold on you in a sense?

They became an important thread through the movie, especially when we thought that my time to dispose of that stuff might be quite short. It felt like I could pretty much let go of everything. Now that I might be alive for decades, it’s kind of like, “Oh damn, I gave that away,” but it’s also unlocked that kind of door where if anybody kind of says, “Oh, that’s something I’ve been looking for for a while,” and I’m thinking, “Am I ever going to watch that again?” I can give it away, start that process. It’s been really good.

But at the same time, there was a certain pride as a collector and having complete collections or having things which, in a weird way, you think you’re collecting on behalf of humanity for some sort of archive, which, in a horrific way, is actually coming true as people are realising that streaming services or people who promise to have the cream of the classic movies and golden age TV are, in fact, publicly saying, “We’re not your archive.” And the stuff’s disappearing.

There used to be the ads on, “Here’s Joe burning a pirate copy of the movie while his friends are already watching it.” It’s completely flipped now. Here’s your friends desperately trying to find the first series of this thing you’re trying to watch, it’s no longer available. But I’ve got it on my shelf here.

There are things that I don’t want to let go of, but it’s been a really good wake-up call to just kind of get rid of an awful lot of rubbish. And it was great seeing the amount of joy at the exhibition, just people, “Aww, I remember that,” or, “I’ve never seen that before,” kids seeing toys that had to be explained to them and stuff. And I’ve actually been stopped by kids in the street saying they enjoyed my exhibition, which was great.

I used to watch people like Chris Knox too. He was a huge hoarder for a long time. And in fact, we shared interest in quite a lot of things, pop culture, movies, and comics, and so on. And there seemed to be a lot of us, but most people end up with families and having to kind of strip away their collection for the money invested, and I haven’t.

So I’ve still got the stuff, which is both kind of sad and pathetic but also proving to be quite interesting in terms of the amount of interest from pretty much all the main archive collections in New Zealand have approached me now for at least aspects of my collection.

At 55, I come from an era where there weren’t a huge amount of toys related to TV or movie things. In fact, it was very hard to find anything. I remember creating my own cardboard Batman figure because it was before you could get action figures or anything. So I was one of those adults who, once that stuff became available, you just kind of naturally bought it, because it’s what you’d always been looking for, without even thinking, “Well, it’s actually just going to sit on a shelf now. You’re not going to play with it.”

I remember trying to play with some stuff in my 30s just to see if I could remember what that was like, just kind of tipping toys on the bed and making mountains out of a duvet cover, and it wasn’t there anymore.

That sounds like a really interesting thing to experience.

It was, and I wonder if other people have done it because you know how it is when you’re lying on a carpet and it is really a battlefield or something. And I just wondered, “Is that still in there somewhere? Can I convince myself with these toys?” And no, they were just little objects.

What was it like to find out that wasn’t there?

In a way, I think more of a relief than a sorrow, I think. Yeah. It was nice to know that I wasn’t going to be plagued by that sort of psychosis as well, I think.

The documentary will be out in front of audiences in cinemas really shortly. Do you think anything’s going to change for you with the release of the film? What are the next few months going to be like?

I think the next few months are going to be interesting because my commitment to the promotional bit kind of goes for quite some time. I think the ramifications from it are going to last a long time. And already, I’m seeing that I’m going to have to really sort of toughen up a bit.

There’s some pretty nasty criticism starting to come out from people who haven’t even seen it yet who just are making assumptions about the content. I’ve seen comments already about the glorification of drug use and this kind of stuff from people who haven’t seen it and that they would not condone it or go and see the movie because of that. I’m of the age group that’s on Facebook and would love to get involved with some of these fights but have learned not to.

Because I know the calibre of this movie and I think it honestly is up there with some of the better ones I’ve seen, then I think it’s going to have a long-lasting effect. And I haven’t seen any band not be severely affected by that.

That’s a really good way of putting it.

The obvious example would be Dig! with the Dandy Warhols and Brian Jonestown Massacre. And that’s a long time ago for them, and yet it is still one of the key links they got to a much larger audience. I suspect that’s going to happen with us, and I don’t think it’s going to be all pleasant. But at the same time, it’s a really good calling card, as you said, to a new audience because you’re showing beautiful scenery accompanied by Chills music, and its kind of like the tourist board should be sort of pretty proud of us too!

I think the filmmakers have done a really good job of showing the intense emotional potential of some of that music, and that’s going to register with people, I think, mostly in a really positive way.

It’s a really, really strong film, and I think you should be very proud of it.

I am. I think we’ve all done a good job. It was pretty intense. There’s been a lot of tears shed, I’ll tell you. And also, the band hadn’t actually seen it until the Austin premiere, and there were a few moist eyes there.

But it also led to a really interesting discussion with the band over the next couple of days about how names of previous members suddenly became faces, and more than that, they realised the impact of having been in The Chills was still a major part of these people’s lives, decades later. And I mean, these people in the band now have been with me a long time and were seriously committed to the band, and it made them realise—just the sheer weight of what we are carrying forward suddenly became more important to them, I think.

That was from a couple of people. A couple of band members said that, pretty much. And I was really, really touched by that, thought it was good, because it’s been hard. There’s so many Chills, and they do turn up at the oddest places on tours, and the band is kind of like, “This is so-and-so. They were in the band.” And it’s kind of like, “Hi. Nice to meet you,” and then everyone’s off kind of doing something else.

Does it sort of pull those former members less out of the realm of being ghosts for your current band?

Oh, exactly. Yeah. That’s the thing. Real people who had seriously emotional connection with the band and still do. Yeah.