New te reo version of The Lion King is much more than a translation

Director Tweedie Waititi tells us: “the foundations of the original film is definitely there but the thinking is different.”

With the release of The Lion King Reo Māori this Matariki, Liam Maguren learned more about this new version from the film’s director Tweedie Waititi and how it’s far more than a translation.

THIS INTERVIEW HAS BEEN EDITED FOR LENGTH AND CLARITY, TRANSCRIBED BY LIAM MAGUREN

There’s no such thing as ‘a simple translation’ from English to Te Reo Māori. If there was, Disney could’ve pushed The Lion King through Google Translate, slapped ‘The Lion King Reo Māori‘ on it, and called it a day. In the same manner, you could put a loaf of bread and the contents of my fridge into a blender, but what you’d pour out wouldn’t be a sandwich.

A proper adaptation requires patience and artistry, and The Lion King Reo Māori is the product of talented experts brought together under the same kaupapa: to honour and expand the revitalisation of Aotearoa’s native language and tikanga.

Joining me on Zoom the day after The Lion King Reo Māori‘s premiere at Auckland’s mighty Civic Theatre, director Tweedie Waititi of Matewa Media was “lost for words with how well it was received.”

Before Waititi and her team built this new Te Reo Māori version of The Lion King, they gained a wealth of experience with Moana Reo Māori. “We wanted to prove to our people and to the rest of the world that we can do this ‘re-version-ing’ [of Moana]. It was a real testing ground. We learned a hell of a lot.”

After the release of Moana Reo Māori, Waititi and her team went on to “cast our net out and see what comes back. Our people wanted more, so we went to get more for our people. It’s a very Māori way of thinking: when the people want, you go and get.” That’s how they caught the dream: The Lion King Reo Māori.

The film might be set in Africa and not star a single Māui, but that was never the point. “I don’t want us to box ourselves in,” Waititi explained. “It doesn’t have to be a Māori story or a Polynesian story. We can translate the world. Well, it’s not even ‘translation’. It’s an ‘adaptation’.”

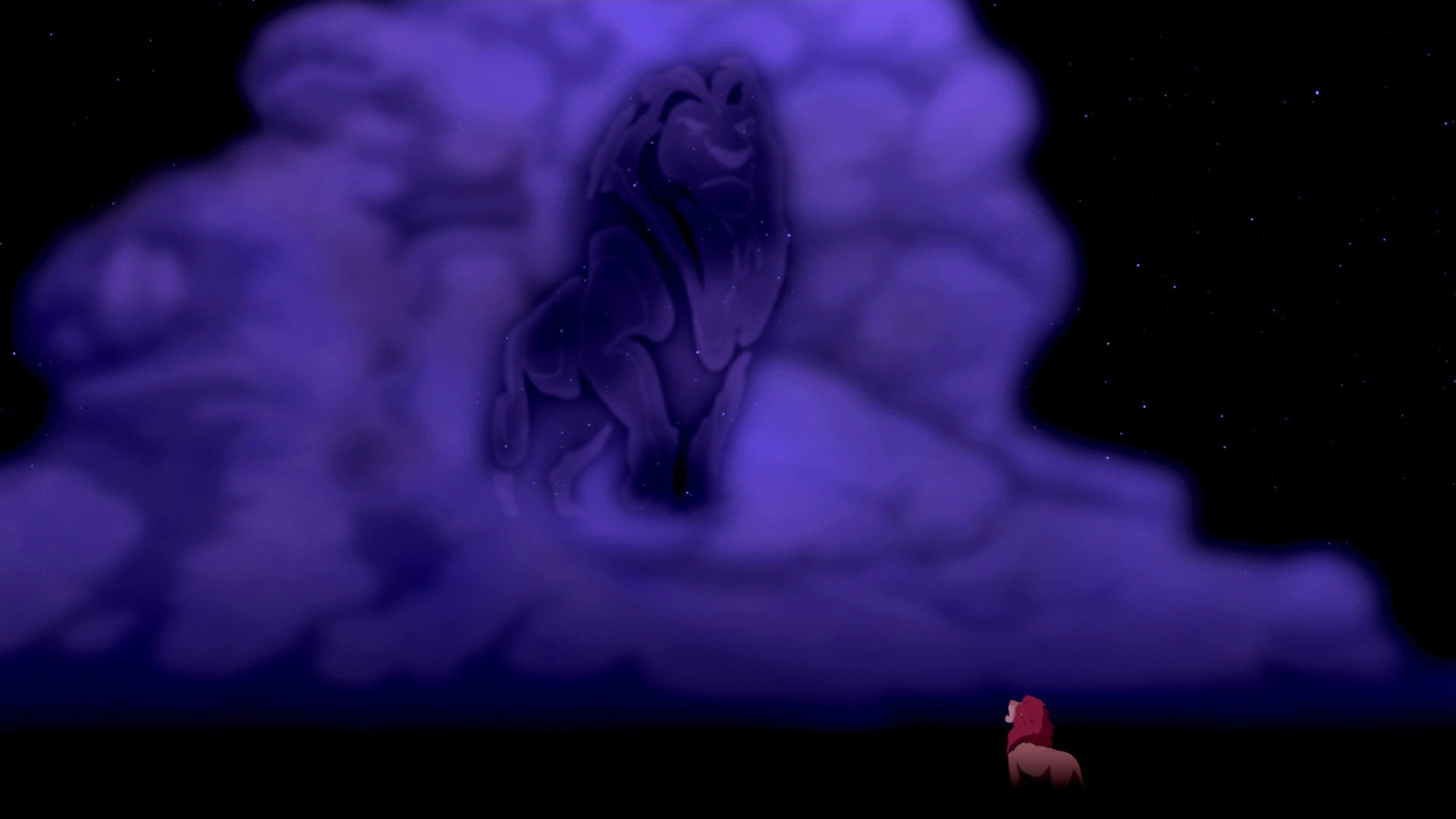

With the film’s release during Matariki, I couldn’t help but bring up the scene with Simba gazing upon the stars while speaking to—and reflecting on—his deceased father Mufasa. I wondered if that moment played a part in determining the release of the film during the occasion. Turns out, “it was a bit of a coincidence.”

“We always wanted to launch a film on a unique date to Māoridom. This is the first time Matariki is acknowledged as a public holiday, so we thought, to celebrate that milestone, let’s pop out The Lion King during that time. But Māoridom have been celebrating Matariki forever. It’s more than a celebration: it’s acknowledging the people who have passed on and heading into wānanga mode. At this time during the cold months, you wouldn’t be outside playing, this is when we do all our deep learning.”

Though that scene may have had nothing to do with the film’s release date, it was one of many examples that highlighted what sets The Lion King Reo Māori apart from the original. “We so did make it Māori, eh? When Mufasa came back, that scene hits everybody differently, just the language used within that scene relates to Māori. ‘Kua Whetūrangitia’ is a very prominent saying. It’s very well-known that that’s how we acknowledge our dead.”

“All those little gems are right throughout the film and we’ve really adapted it to Te Ao Māori. We don’t really like just translating the words. Otherwise, we may as well just make an audiobook. You have to really adapt it so that it appeals to our people. If you don’t really adapt it, you can throw people off the scent because [it won’t show] our way of thinking [or] our way of speaking.”

“For example, in the English [version], Scar says: ‘Well, I was first in line until that hairball was born’. Then Mufasa says: ‘That hairball is my son.’ In the Māori version, he says: ‘Ko tā tāua tama.’ ‘That’s our son,’ because you’re always raised by a village. We don’t own our children. It’s our job to make them and it’s the iwi’s job to raise them.”

“It’s putting everything into that context. It’s actually a new film, now. The foundations of the original film is definitely there but the thinking is different.”

That thinking weaves through the very construction of the film. “You gather your teams and we all share the same vision. It’s a collaborative process. There’s not just one director. There’s not just one producer. We all get equal say in the creative process. Otherwise, we’re not operating as a Māori operation. We’d keep massaging the reo until we’re all happy. There are no egos in the way. This is not about us. It’s bigger than us.”

This Māori operation isn’t stopping anytime soon, with Frozen Reo Māori due for cinemas end of September. I asked Waititi what else they have planned for the future. “Like I said at the beginning: we’ll cast our net out and see what comes back. I think we owe it to our language and our people to get more.”

“You can translate a book, an album, songs and things like that. But I think films are the real pinnacle for translations because you’re seeing the language in context and hearing how it should be delivered. We are still working on the survival of the language. We have to normalise our reo and have a hell of a lot more resources out there to help our people along, whether they’re Māori or non-Māori. Film is a nice, accessible way to learning te reo.”

“It’s also a place where we can hold a lot of mātauranga. There’s a lot of mātauranga in The Lion King Reo Māori that will live on for years. The film is 28 years old and will live on for another 28, with a new life.”