Sex, death and glory: Scorsese’s life in 15 films

The subject of new five-part Apple TV+ docuseries Mr. Scorsese, the iconic director proves abundantly generous.

“They aren’t violent until I’ve edited them,” goes the immortal quote by Martin Scorsese’s ride or die editor, Thelma Schoonmaker. But as the director and undeniable cultural titan makes clear in Mr. Scorsese, Rebecca Miller’s Apple TV+ docuseries, the darkness was all around him from the beginning.

Related reading:

* Scorsese’s black comedy After Hours is one of the best films of the ’80s

* Killers of the Flower Moon leaves a devastating impact

* Leo’s great streak playing complete losers continues in PTA’s latest

Born in Flushing on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1942, his parents, Charles and Catherine, had emigrated from Sicily, working in the Garment District under the thumb of Mafia gangs. Scorsese recalls his father telling him, early on, never to accept a favour from any of these men. It wasn’t uncommon to find bloody bodies on the street.

With asthma, Manhattan summers could be punishing for the young Scorsese. So he and his dad retreated to movie theatres, allowing him to breathe easy in their aircon. It’s where the world came alive for him, through films like The Big Heat, The Wizard of Oz, Bicycle Thieves and Duel in the Sun, the latter providing his first thrill of sexual arousal.

Scorsese insists we must wrestle with the darkness as well as look to the light. On that note, let’s explore Mr. Scorsese’s insights into some of his key movies.

Delivering his first feature, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, while studying at NYU with Schoonmaker, Scorsese fell in with the indie gang of Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma, George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola. But he was burned when he was dropped from a co-directing credit on seminal documentary Woodstock. Moving to LA, exploitative producer Roger Corman threw Scorsese this saucy crime drama with next to no budget. Mentor John Cassavetes had this advice for Scorsese: “You just spent a year of your life making a piece of shit. Don’t do it again.”

Cassavetes essentially told Scorsese to write what he knew, leading to this Little Italy-set crime drama drawing on the darker elements of his childhood. De Palma introduced him to De Niro, cast as Johnny Boy, kick-starting an enduring cinematic partnership. But not everyone was pleased with the film’s colourful language. After its New York Film Festival premiere, Catherine Scorsese told journalists he didn’t speak like that at home.

Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore

At the height of her powers and energised by the feminist movement, Ellen Burstyn wanted a new and exciting director on what would become an Oscar-winning road trip for the Exorcist star. French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard loved it, but Scorsese says the ego trip of heroes calling him a genius paved the way to drug-fuelled days.

Scorsese leapt on this Paul Schrader screenplay when De Palma passed on it, uniting De Niro with Alice child actor Jodie Foster in astonishingly uncomfortable fashion. Her abiding memory is excitement at the special effects team using Styrofoam in fake blood, so it stuck to the wall in clumps. Spike Lee insists Scorsese wasn’t using violence gratuitously, instead speaking truth. It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

Pairing De Niro with Liza Minelli, this musical leaned into its artificiality as an ode to the movies Scorsese loved as a kid. He believes music is the purest art form. Full of cocaine in this era, he says he and Minelli were like whirlwinds, acknowledging that not all the improvisation works. It bombed, big time, temporarily sinking his long-held dream to make Gangs of New York and The Last Temptation of Christ.

De Niro visited a death’s door Scorsese in hospital after he collapsed from all the drug use, pumped with cortisone for ten days and nights. The director says he died there and was reborn, agreeing to make this striking black-and-white Jake LaMotta biopic with his star. Scorsese also reunited with Schoonmaker. They’d cut the movie all night until the birds started singing, when Scorsese’s then-partner, Isabella Rossellini, would get up.

Paranoid after the assassination of John Lennon, Scorsese became a bit of a recluse and was reluctant to make this psychological thriller about an obsessive would-be stand-up kidnapping his idol, eventually talked into it by De Niro. Rossellini recalls a ferocious temper that fuelled his filmmaking during this era. “Rage gave him that stamina.”

Schrader says they set out to upset stuffy religious naysayers with this remarkable portrait of Jesus, played by Willem Dafoe and shot in Morocco for very little money. Scorsese retorts, “I didn’t think they’d be this upset.” A screening at the Saint Michel cinema in Paris was bombed, spookily injuring 13 people. TV nun Mother Angelica dubbed it, “The most satanic movie that’s ever been filmed.”

The studio was baying for cuts to this De Niro-led return to mafia material, but Scorsese stood his ground. It provided another great turn for his mum, who notes, in archival material, that her son only ever gave her the first line, encouraging her to improvise the rest. She had to do her Mean Streets scene 22 times and was pissed he cut her from Taxi Driver. “I don’t like it. I work so hard.”

Scorsese’s daughter Domenica, from his marriage with second wife Julia Cameron, fondly recalls appearing in this Michelle Pfeiffer and Daniel Day-Lewis-led period drama. As with her elder half-sister Catherine, he wasn’t around much when they were kids, so being on set was a way to meet him on his level.

Schoonmaker refers to this monumental, Vegas-set mafia epic as Scorsese’s Mount Rushmore. Sharon Stone, as the unattainable Ginger to DeNiro’s determined Sam, says she was only meant to be on set for five weeks but wound up stuck for five months. Fully committed, she did not care.

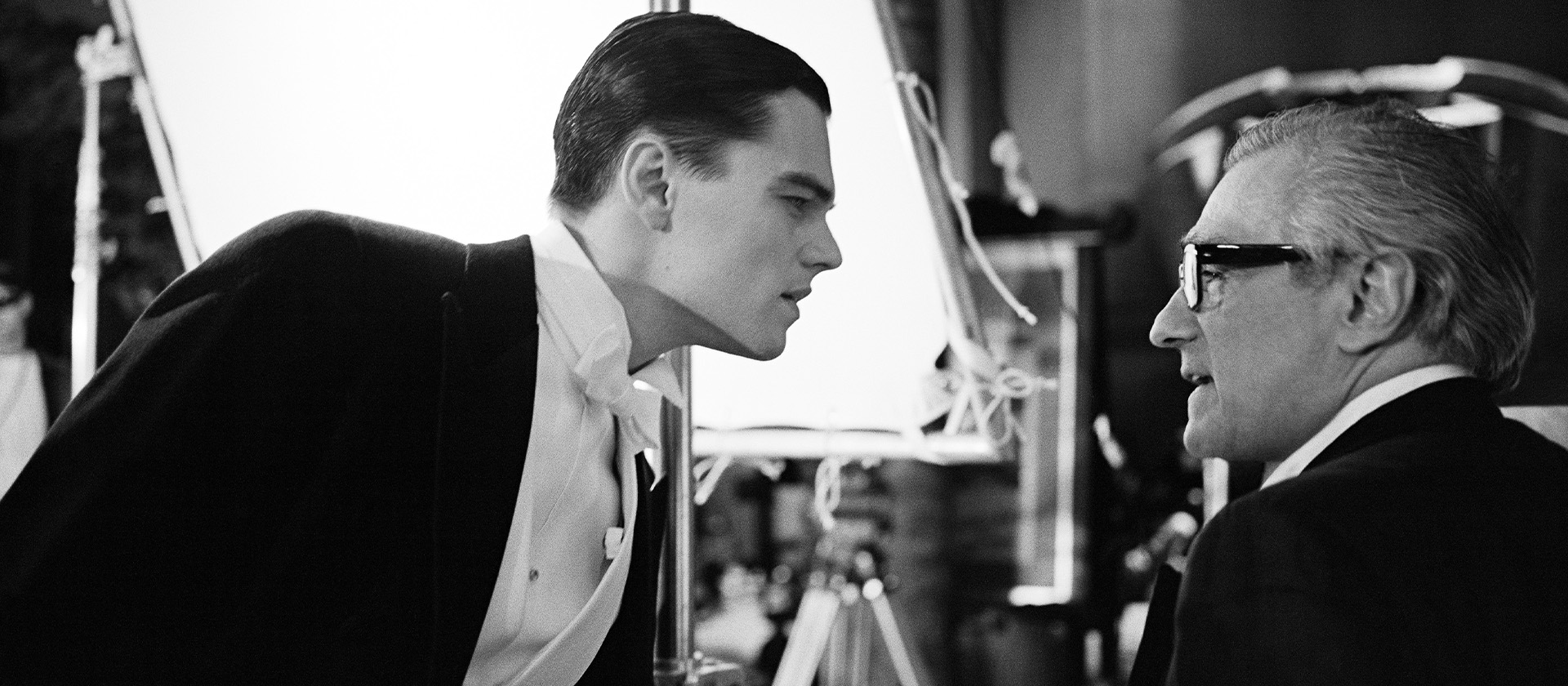

Finally achieving the second of his career dreams, after The Last Temptation of Christ, this origin story of his hometown was the biggest thing he’d ever attempted. De Niro introduced him to Leonardo DiCaprio, who was big enough after Titanic to help fund it himself. Nevertheless, the not-yet-disgraced Harvey Weinstein rampaged behind the scenes as budgets kept blowing on an infamously fraught set. A desk went out a window.

Luminous Australian star Cate Blanchett says Scorsese had an affinity for aerospace magnate and film producer Howard Hughes, the subject of this lavish biopic, who was as obsessive and meticulous. DiCaprio, the Hughes to her Katharine Hepburn, concurs, saying he almost lost his mind with how specific and intense each shot was. Accruing 11 Oscar noms and five wins, Scorsese was again overlooked in the Best Director category.

An oversight finally corrected with this dazzling remake of Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s corrupt cop crime thriller Infernal Affairs, relocating the action from Hong Kong to Boston and partnering DiCaprio with Matt Damon, Jack Nicholson and Mark Wahlberg. Best buddies Spielberg, Coppola and Lucas presented the golden statuette to Scorsese. He muses that he doesn’t know if his hubristic weakness could have taken it any earlier.

It’s hard to remember, but the ubiquitous Hollywood powerhouse that is Margot Robbie was still relatively unknown when, at 22, Scorsese cast her opposite DiCaprio as crooked stockbroker Jordan Belfort. Always a sharp storyteller, she worked with both men to tease out the chaotic scene when she finally leaves her philandering husband, something Scorsese has always encouraged his actors to do.

Rebecca Miller and Martin Scorsese in Mr. Scorsese

It’s understandable, given a career this deep and rich, that Miller, a gifted storyteller who is married to Day-Lewis, must make some tough calls. Scorsese’s TV work, including Boardwalk Empire, is left to one side. His most recent movies get shorter shrift, including, surprisingly, Apple TV+ hit Killers of the Flower Moon, leaving me wanting a sixth episode.

There’s talk of fatherhood and the consequences of your actions, pegged to De Niro’s lonely fate in The Irishman. The tenderness of Scorsese’s love for his youngest daughter Francesca and care for his wife Helen Morris, who has Parkinson’s, is some of the most affecting stuff in this five-hour masterclass. Revelling in a life well lived, whatever its ups and downs, Mr. Scorsese is a gift to us all.