Blowing the call centre industry wide open, Telemarketers is unmissably great

A motley crew of burnouts and ex-cons blow the whistle on a wild charity scam in HBO’s docuseries Telemarketers. Luke Buckmaster says it’s a call you should definitely pick up.

For too long have they been pilloried: those humble and unfairly maligned telemarketers, bravely interrupting us during dinner to encourage better investment of our time and money. Yeah, nah. The hatred everybody shares towards those gasbagging cretins will continue, if not intensify, in the wake of Telemarketers, a work of citizen journalism par excellence that, thank god, wasn’t another bloody podcast but a three-part TV series stuffed full of great footage.

“Great” in this instance referring to tonnes of camcorder-shot moments captured inside the belly of the beast: a now-defunct company called CDG that had enormous influence on the telemarketing industry. The company stitched together a deal with many charities—including those representing police, firefighters and cancer survivors—allowing them to cold call people on each organisation’s behalf, using the charity’s name, asking for donations. The charity received 10% of the money given.

The show, directed by Adam Bhala Lough and Sam Lipman-Stern, begins with Sam Lipman-Stern—a former CDG employee who filmed all that footage—lying in bed, reflecting on how he’s been “feeling like fucking shit” and has wanted to make a documentary about the company’s dodgy goings-on “since I was a fucking kid.” By “kid” he means young teenager—Lipman-Stern was hired when he was 14—but if Telemarketers revealed CDG used actual children, you wouldn’t be surprised.

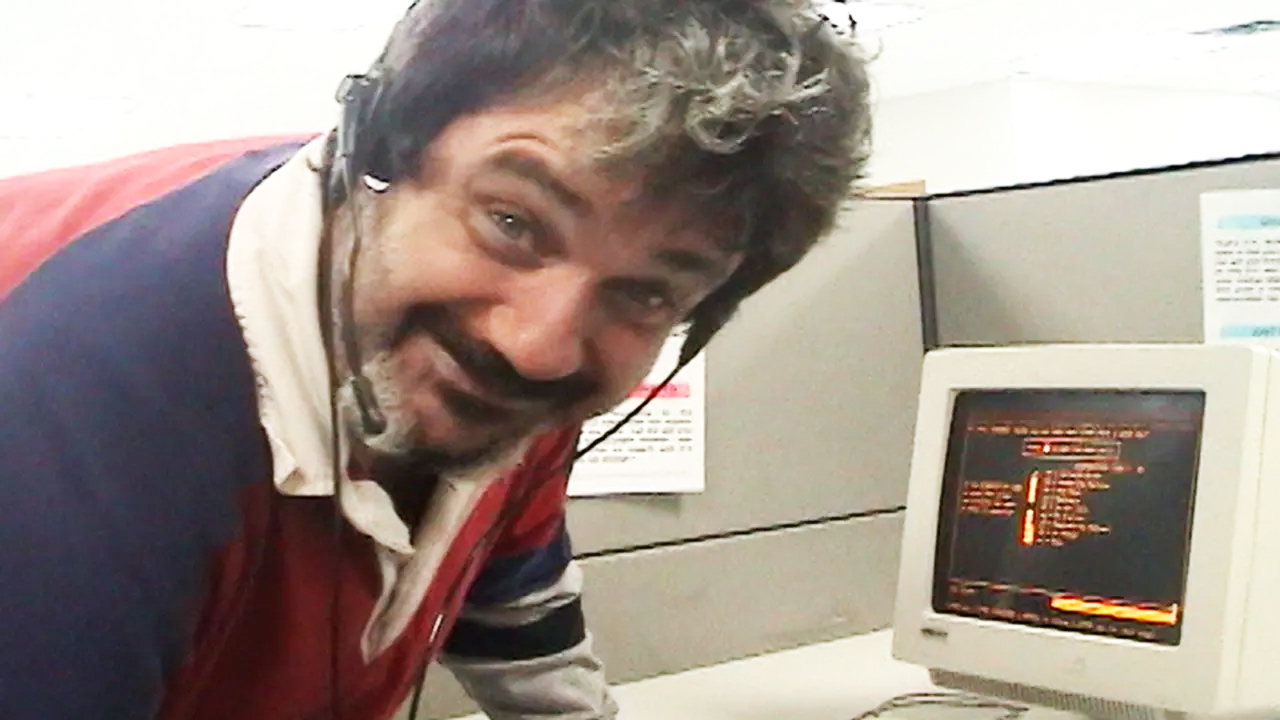

The directors cut to footage of the call centre: a place Lipman-Stern describes as “crazy” and “insane,” though its soulless decor and ratty cubicles imply something awfully mundane and spirit-crushing. The filmmaker narrates that he “could never have imagined [he] was part of the biggest telemarketing scam in American history,” but his colleague Pat was “on to it from the very start” and “born to be a whistleblower.” Pat (Patrick J. Pespas) appears in the next scene, rambling about how they “call up people on behalf of some bullshit organisation and chisel ‘em out of money.”

Pat has a deep squint when he says that, his left eye falling towards the floor, as if there’s tiny sandbags above it. He looks sozzled, bent, baked. Says a colleague in the first episode: “Everybody loved Pat. He had that drug problem, but everybody loved him just the same.” The endearing and loquacious Pat (what they call “great talent” in documentary land) isn’t shy about his fondness for drugs, wolfing them down in front of the camera and being obviously wasted at work.

Such behaviour wasn’t rare for CDG employees. They were a collection of outcasts, drifters, dropouts, ex-cons, no-hopers, shit-spinners, second-chancers. Plus anyone else who blew in through the door. The company didn’t care who they were or what they did: if staff reached their quota they were all good. This dirty philosophy had unintended societal benefits, in that CDG was one of few companies—and even fewer in office environments—that employed people with criminal records.

Watching the telemarketers work their magic, wagging their dope-tanged tongues, highlights performative aspects of the work: it’s all in the vocals, knowing the script, knowing the rebuttals, having the gift of the gab. I assumed the series wouldn’t stray far from the CDG office. But oh boy, it becomes much more. It’s thrilling to observe the scope expand from compilations of fly-on-the-wall footage and tell-all interviews to richly layered underdog journalism, with great vertical energy: a feeling that it’s rising from the streets, towards the highest echelons of power.

One interviewee, whose appearance and voice are disguised, verbalises the series’ intensifying mood with a deliciously cloak-and-dagger soundbite, straight from a Hollywood script. “I don’t think you understand,” he tells the filmmakers. “It’s not the telemarketers you should be worried about.” Given the organisations CDG represented include several police charities…could the cops be in on it?

Shot over two decades, with lengthy gaps between filming, we see people come and go, members of the old CDG gang getting new jobs in an industry one expert compares, in its capacity to be regulated, to the Somali pirate trade. We check in at various points in Sam and Pat’s lives (not conceptually dissimilar to how the Seven Up! series unfolds) to see how their friendship has developed, and personal narratives—which in part are tales of redemption—have expanded.

One of the core messages is that it’s never too late to do the right thing, no matter how many wrongs have come before. It doesn’t matter that these unlikely heroes, determined to bust the telemarketing trade wide open, didn’t solve the problem, didn’t stop the scamming. Just believing in the possibility of change can be powerful and beautful. What’s more important: achieving results, or doing the right things for the right reasons? From the muck and filth of the telemarketing trade emerges a moral lesson for our times.