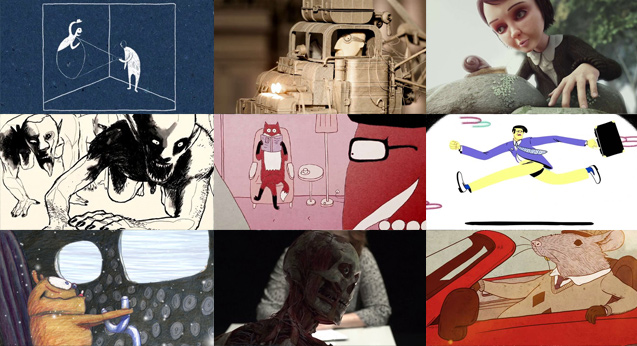

A deep dive into NZIFF 2018’s animated wonders

“The festival is the only way you’re going to see these on the big screen.”

Animation NOW has been a staple in the Auckland portion of the New Zealand International Film Festival for quite some time, curating and displaying some of the world’s most jaw-collapsing, mind-twisting, eye-soothing animated shorts from around the world. This year, the showcase gets its own weekend (August 10-12) after the main portion of the Auckland festival ends.

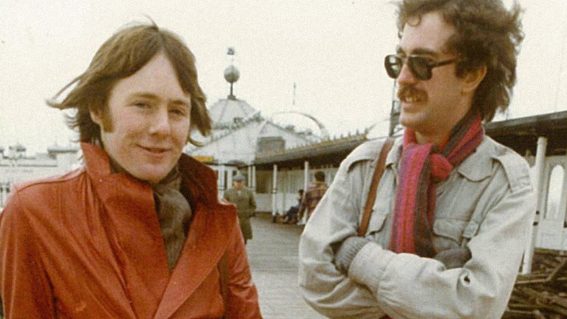

We talked to curator Malcolm Turner about this year’s selection, what inspired each programme, and the films that excite him the most.

FLICKS: Let’s talk about how you organised these schedules. The one I want to talk about, first, is the Fresh Eyes on Estonia programme.

MALCOLM TURNER: I’ve been a big advocate of Estonian animation since I became involved in animation. A lot of people don’t realise, I think, how utterly unique Estonian animation is. It harbours some of the greatest animators that have ever worked. Priit Pärn, for example, is widely regarded as a living master, one of the true living masters of the art form.

There’s a really interesting element to this particular focus on the Estonian programme. In the past, if you’ve come to the programmes that have been in the festival, you’ll have heard me introduce various Estonian films. This one takes a look at the generation that’s emerged and has become fully trained and experienced in the post-independence period.

For a lot of the 20th century, Estonia was essentially behind the Iron Curtain. It was under the control of the USSR. An enormous amount of their animation was full of all of these hidden, coded critiques of that particular political system. And it was famous for it. They were better at it than anybody. But in 1991, they became nominally independent, and they’ve become increasingly independent over the sort of following decade.

The current generation of Estonian animators, they know that history. They know it, but they’ve never lived it. And of course, they don’t have to make films that have any hidden critiques in them. If they want to critique society, they can say it out loud. If they want to talk about other stories, they can. They’re not driven by all the issues that you had when you’re basically living in an occupied country.

For quite a while, for a decade or more, there’s been a lot of interest in whether they’ve been robbed of those kinds of subversive, political influences, and if Estonian animation would necessarily maintain its uniqueness. And it has. The drawing styles are much the same, the kind of love of the unique puppet animation styles they make at Nukufilm.

It’s all held, and we’re now seeing it in the films of people like Chintis Lundgren. Her film Manivald closes the Estonian programme, and it’s one of the hottest films on the international animation festival circuit at the moment. It’s a co-production with the National Film Board of Canada, and those guys don’t take on those things lightly.

The thing I love about Chintis’s work is that she’s writing from a very confident female perspective. Her stuff is poetically strange in a certain sense and she still handmakes. It’s all hand drawn. She colours it up a little bit, balances colours and stuff with computers, but it’s all hand-drawn.

And you look at the film that opens the programme, Ülo Pikkov’s latest film Letting Go. Pikkov writes extensively on the philosophy of animation. He’ll probably be the most thoughtful kind of person writing and working in that form. And his film is probably one of the most confounding in the festival.

It’s co-curated by me – well, I kind of did the mentoring rather than the curation – and Australian filmmaker Annie Murray, who’s an accomplished filmmaker in her own right. Annie will be in her early 30s and she actually went to Estonia under her own steam and connected with all of those people. So she was able to connect with that generation of Estonian filmmakers in a way that me, as a 97-year-old white guy, had no hope of doing. She was particularly able to connect with the younger female animators there, come back with some great stories, and has put together a programme that would be different than the one I’d put together.

With Morph’n’Move and Crazy Towne, if you took one glance at it, it looks like it could just be one and the same, or the Venn diagram looks really close. But what really defines each of those?

Other than the Handmade programme, Morph’n’Move‘s probably got the clearest thematic thread to it.

I love films that make the best use of all the unique properties of animation. One of them is this incredible ability to morph things, to take any figure you want and change it really quickly, really smoothly, really imaginatively, into something utterly, utterly, utterly different. It’s an artform that does that better than anything else. Probably the only other art form that comes close to it would be poetry.

The opening film, Knockstrike, is a great example where you’ve got a human-like figure walking down a street and taking these giant steps forward. The legs go way up into the air and come down, and then this (what seems to be a) tiny little body comes zooming forward and past the legs, and wrapping around the legs again. Sometimes the character wraps himself around the environment he’s walking through. Sometimes the environment kind of swoops in and almost overwhelms him.

We made a decision pretty early that we were going [with this theme] because we had a few great films early that came and just were like, “We’ve got to have a programme about morphs.” It was, I think, the first of the programmes to be completed.

Is the madness in Crazy Towne more thematic?

Yeah, there’s some pretty wild imaginations out there in the world of indie animation. And some of them just want to see things blow up, or make things blow up. Every animator is a little god in their own right.

We have things like Cop Dog, Bill Plympton’s latest film. It’s just nuts. It’s about a dog that takes over a plane when the pilots take psychedelics, and the whole plane turns into a party plane. And there’s a fire crew that wind up causing explosions. I’m not going to tell you how it ends because that would be a bit of a pity, but it ends in flames in both senses.

Could I take a 12-year-old cousin to Crazy Towne?

Yeah, absolutely. Dark Hearts is probably another story.

Animators are like any other artists. We’ve got, I don’t know, 70 or 80 films in here. If you sat down 70-80 short-filmmakers, or 70-80 poets, or 70-80 painters or whatever, a decent percentage of them are not going to be writing or filming about a happy day. Often, artists want to pursue things that they find disturbing, or shine lights on things that they think are being ignored or need to be discussed, or they’re deliberately trying to be confrontational about something that’s on their mind. And those films go into Dark Hearts.

Some of them are a little more light-hearted than others, but in some cases, there’s some fairly confronting kind of issues that are being tackled by those people, and in really uncompromising ways in some cases.

It made me really happy to see handmade animation getting its own programme.

Yeah. It’s my way of just reminding people that the field of auteur animation hasn’t been consumed by computers.

We had over 4,000 submissions. I’ve never really done the numbers, but my guess is about only a quarter of them I would classify as CG. And there’s no question that computers play a role in a lot of animated film, even in handmade films.

If you shoot it digitally, you now are able to contort your puppets into ways that would have never been supported before because you can stick wires on them and stick supports on them, and then just scrub those in post-production. So puppets are now, in many cases, more fluid, they’re more active, they act more because they can be put in all these positions that couldn’t have been supported in the past when we couldn’t do a lot of that. But it’s still handmade. It’s still the filmmaker doing his or her thing with their own hands.

A great example is the opening film in Handmade, Negative Space, which I think is gorgeous and has won hearts all around [the NZIFF office]. Everybody just loved it.

One of the things I like about this stuff is that you look at it and go, “I could do that.” And of course, I couldn’t, but you get the impression that you can get these things made, just move them around, and shoot them. It’s a very direct feel between the imagination of the animator, which is something that’s only in their head, and your eye.

It’s not just puppet animation. A lot of hand-drawn, hand-painted animation being made. More than 50% of animation that I see has been substantially handmade in some way.

What inspires the International Showcase? Is it made of films that didn’t fit into other categories? Or is it the best of the best?

It’s a little bit of both, to be honest. We get a lot of films that we’ve got to show, but don’t fit into any of these themes. And that’s where the International Showcase comes in.

With Threads, Torill Kove’s new film, all of her films are must-haves, in my mind. Academy Award-winner, beautiful animator who’s got a really lovely, personal, familial kind of storytelling thread that runs through all of her films. And this one didn’t let down.

Ugly, which probably might have fitted in Crazy Towne, has a really muscular use of 3D CG that I haven’t really seen in a cinematic short for a very long time, if at all. They’ve thrown everything they have at it. There’s an impact with every scene. Things are moving all the time. Things are crashing down all the time. It’s high-octane stuff. It was a film we had to work really hard to get, probably the hardest film to lock in. But it won the top prize at Ottawa and it was controversially left out at Annecy. It’s polarising. Some people love it and some people find it too much. Some people wonder what it’s about. I don’t think it’s about any one thing. It’s the same sensation you get from looking at a painting or reading a poem. It’s not necessarily specifically about something. It’s designed to generate a reaction within you.

It wouldn’t be a film festival without something divisive.

That’s right. The festival situation is the only way you’re really going to see these films on the big screen. There’s just no other opportunity to show these.

There are two New Zealand shorts in the programme. How did you go about choosing those?

They came to us. We were lucky enough to have those submitted through the open submission system and they were both instant grabs. They’re absolutely world-class.

Tom is in Dark Hearts. It’s a hybrid of live-action, pure CG animation, and motion capture. There was an international motion capture showcase at the Melbourne International Animation Festival last week, put together by the Motion Lab people at Deakin University in Melbourne. They’re among the best in the world, and this film is as good as anything that was in that. Kind of spooky, too.

Trap is a different thing, a much slower burn. It’s about a young girl that finds herself a little bit trapped in a very, very unhappy foster family type of situation. As far as I can tell, the intent of the filmmaker is to make that part of the story real. You meet her, you meet the father and the mother, or the husband and wife, I should say, and you learn about her living environment and the demands that are now being placed on her, and how her life is gradually being chipped away by the fact that she’s essentially being turned into a slave, in a certain sense. It becomes murkier as she starts either plotting her revenge or daydreaming to escape the situation she’s in.

Pretty simple idea, in some ways, but very clever narrative structure. Really interesting. Not twisting time, but twisting the spaces in which a story is explained to an audience, or uncovered to an audience. And one that can really be only done with animation. You can only play this story out in that way, using the unique properties of animation. And that’s why I picked it.

Find more on the Animation NOW programmes over at NZIFF.