B is for The Box: a moral dilemma that spirals into total sci-fi nonsense

In monthly column The A-to-Z of Trash, bad movie lover Eliza Janssen takes us on an alphabetically-ordered trip through the best bits of the worst films ever. She still doesn’t know quite what’s going on in Richard Kelly’s The Box, but she has fun trying on his tinfoil hat for a minute.

Why a box, an underling asks shadowy bad guy Frank Langella? Why The Box, you ask me, the writer of this column celebrating the bewildering beauty of bad movies? Well, Frank explains: “your home is a box. Your car is a box on wheels. It erodes your soul while the box that is your body then inevitably withers and dies. Whereupon it is placed into the ultimate box to decompose.”

“It’s quite depressing when you think of it that way”, the lackey replies. It’s also a massive, shoulder-dislocating reach for meaning, in a film that gets all the more mysterious and nonsensical the more you look at it. Released in 2009 and earning one of Cinemascore’s very few ‘F’ ratings, The Box is a brow-furrowing embodiment of the mid-2000s ‘mystery box’ storytelling trend. Open it up today, and you might just find some thought-provoking themes and potent thrills, nested deep inside director Richard Kelly’s trademark bonkers world building.

Back in 2001, Kelly’s conspiratorial cult classic Donnie Darko seemed to capture the teen angst and ennui of its time period, charming and baffling audiences in equal measure. Even 2006’s Southland Tales, a gonzo dystopian satire featuring The Rock, Justin Timberlake, and Sarah Michelle Gellar as paranoid doomsday prophets, has a fanbase of apologists. Each film is infested with interdimensional CGI portals; brainwashed ‘agents’ of some higher spiritual force; odd bursts of genuinely solid humour (who could forget Donnie Darko yelling across the dinner table that his sister “can go suck a fuck”?).

Both films are wildly creative, idiosyncratic, and grandiose in their hard-to-pin-down mythology. But by attempting to adapt a neat, elliptical short story from sci-fi great Richard Matheson, Kelly (paradoxically enough) boxed himself into a more serious thriller format, that unfortunately exposes the most frustrating facets of his style. You can tell that Warner Bros. didn’t know what to make of the finished product, too: the trailer above (weirdly soundtracked to “Hello Zepp” from the Saw franchise??!) barely gives us a glimpse of the movie’s wacky, watery metaphysical moments, framing the project more as a simple crime-thriller.

James Marsden and Cameron Diaz play 1970s couple Norma and Arthur Lewis with super drawn-out Southern accents and perma-gloomy faces. Just as Marsden’s been rejected from his astronaut dream and Diaz learns she can’t afford their son’s schooling fees anymore, Langella’s eerie stranger Arlington Steward shows up at their door with a tantalising, double-edged proposition. They can whack the button on the mysterious box he’s left them, and instantly receive a million dollars…but “someone they don’t know will die”. Question: why isn’t this story called “The Button”? Seems like the button is more significant than its container. Whatever. Like Eve, Diaz gives into temptation and smacks that mfing like button, not entirely accepting the consequences of what violence may come next.

Published in Playboy in 1970, Matheson’s original story ends with the husband getting killed in an accident and the wife receiving his million-dollar life insurance settlement—because do we ever really know our loved ones? In what I think is a better ending, The Twilight Zone adaptation of Matheson’s tale ends right when Steward leaves the family home. He hands over the cash and notes that the box will be reprogrammed and offered to a new set of strangers. Someone our hero couple “doesn’t know”.

That’s where original versions of this nifty moral quandary leave off—a basic tale of karma’s ironic fallout. In Kelly’s take? Baby, that’s just act one: prepare yourself for the most confusing, moody X-Files episode you’ve never seen, with intergalactic NASA conspiracies, glowing motel swimming pools that lead to eternal damnation, and WAY too much discussion of Cameron Diaz’s disfigured toes.

Yep: disability is an oddly significant element in this tinfoil hat of a film. Every character we meet is absolutely obsessed with the fact that Diaz’s suburban mum is missing four toes on one foot due to a debilitating radiation injury. We get sorrowful camera pans down to the foot; a romantic moment in which Marsden crafts her a foot prostheses; etc etc. When she herself meets Langella’s spooky company man, who is missing a great chunk of flesh from the side of his face after an, um, alien lightning encounter, she tearfully admits that she’ll never feel sorry for herself ever again.

The theme kinda comes full circle in The Box’s climax, in which the box-whacking duo must make another life-or-death decision: either Diaz must die, or their son will mystically turn deaf and blind. Her teacher character spouts Sartre at high school students, quoting that “hell is other people”—something that Langella’s antagonist, with his morality-testing knick-knack, seems to prove true. But in Kelly’s strange, detached script, where characters act like they’ve never met a disabled person before, it seems that the auteur believes hell truly lies in perceived physical imperfection. To live without hearing or, god forbid, four toes, is treated as a fate worse than box-inflicted death.

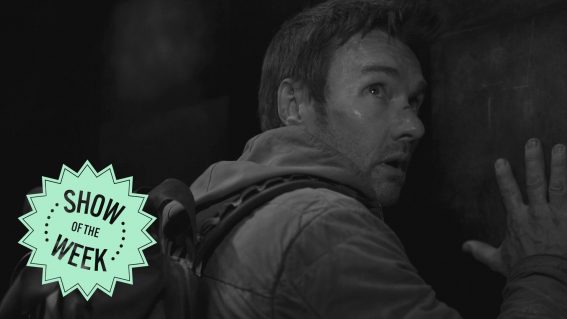

Despite its impossible-to-summarise-here plot and those moments of moral silliness, I love The Box’s chilling inclusion of the seemingly omnipotent Steward’s “employees”—brainwashed worker drones who stand around threatening the Lewises in genuinely unnerving scenes. My fave moment is a clear rip-off of the brilliant phone scene from Lost Highway, but it still hits when Cameron Diaz turns to see a slack-jawed stranger peering into her kitchen window. Here he is, below. I would instantly shit out all my organs if I turned to see this outside my house.

Once you’re an hour and ten minutes into The Box, feel free to abandon all hope of grasping its NASA intrigue plot at all. Gillian Jacobs plays a government-programmed babysitter. The 1970s setting offers some fun fashion and soundtrack choices. And most of all, we’re left feeling as if we’ve seen something that no other writer-director would have the conviction to create: a hare-brained, lore-heavy expansion of a simple ‘what would you do’ sci-fi story. One that feels as though the creator truly believes himself some kind of whistleblower for a vast, post-human government conspiracy.

I want to believe—and, to be perfectly honest, I want to hit that button and cash in, gloopy soul-portal consequences be damned.