“Cuz was a direct reference”: James Cameron and Cliff Curtis on Avatar’s NZ-ness

“There’s obviously a very strong Indigenous cultural component here in Aotearoa, and that has informed, especially, The Way of Water and Fire and Ash.”

You can see the full James Cameron interview in our video embedded at the end of this piece.

My favourite thing about the Avatar movies is how a certain Aotearoa New Zealand-iness positively shines through the screen. It makes sense, considering they were shot here, and are overseen by New Zealand resident James Cameron.

But I wanted to know how intentional that New Zealand-iness is, and perhaps examine the degree to which I may have been projecting this hopeful interpretation on to these gargantuan movies. So when I recently go the chance to sit down with Cameron, my childhood hero, I began by asking him how living in New Zealand has affected his approach to the films, and indeed their content.

“Well there’s obviously a very, very strong Indigenous cultural component here in Aotearoa, and that has informed, especially The Way of Water and Fire and Ash,” Cameron, who shot the first movie in New Zealand before later becoming a resident. “[With the first] Avatar, I was still living in Los Angeles at the time, and it was imagined there.”

“What I could say from the experience of the first film was: great crews, great imagination, great artists and so on. But I don’t think [living in New Zealand] informed the storytelling quite as much as on the latter films. And I think on average, at least Kiwis are pretty pro-nature—[we] love it, enjoy it and protect it, I would say a lot more than most other countries right now. So that’s obviously a key theme of these films.”

Cliff Curtis at Wellington premiere

When I later got to speak to Cliff Curtis [Te Arawa, Ngāti Hauiti], who plays Metkayina clan leader Tonowari, I asked about his experiences following the release of the second film, and to what degree he sensed that global audiences realised how much that particular clan seemed to be channelling aspects of Māori culture.

“I think it’s mix and match,” said Curtis. “Like, some people don’t even still don’t even know that Māori is a thing, that it even exists. Of course, Māori recognise it. I had numerous conversations with [late producer] Jon Landau and James Cameron about this. We get mixed reactions. In my community, we’re really proud of how much of that is present in the film, overall. But I think it’s healthy that we get diverse reactions, and people feel different feelings, and we can sort of be straight up and honest about it. I think it’s good.”

James Cameron greeted with a Māori hongi at Wellington premiere

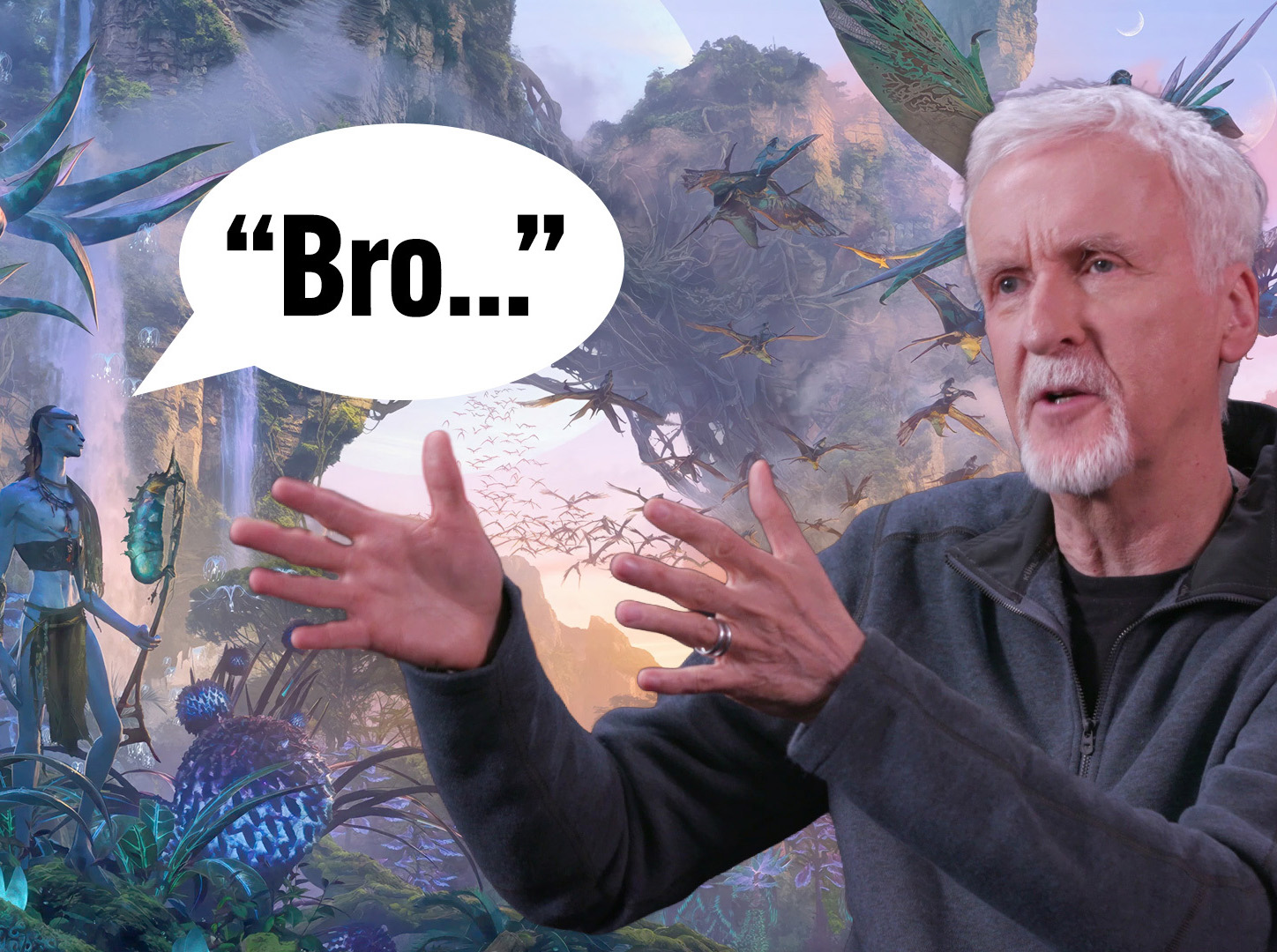

Back to Cameron, to whom I posited that the heavy usage of the word “bro” by the younger characters in the second and third movies may have been inspired by Kiwi kids over-indexing in that particular vernacular.

“What I had in mind was that, from Neytiri’s perspective, Spider as a human kid, is actually contaminating her children culturally by teaching them all this colloquial slang. So that might have been in the back of my mind. But don’t forget that one of the reef kids uses ‘cuz’. That was a direct reference [to New Zealand].”

Like multiple generations of film lovers, I was hugely inspired by the hardware in James Cameron’s films—like the walker and the ‘steadicam’ guns in Aliens, the hunter killers in the Terminator films, not to mention the Terminators themselves.

The new film features some very cool new hardware and vehicles, so I asked Cameron if he is still as excited as he always was to delve into those aspects of the filmmaking.

“Oh sure!” he exclaimed with a slightly manic glint in his eye. “I mean, look, it’s a balance, right? We actually have a separate production designer who does all the human technology and the new aircraft and all that, and he and I geek out together. Then we have a separate production designer who does all the forests and the creatures and the Na’vi and their wardrobe and and so on. I know that I’m dealing with the two hemispheres of the brain, so to speak, but I like both parts of it.”

“And we have to fear this alien invasion. So the more badass their machines are, the better that works, story-wise. Our perspective is supposed to be with the Sully family and with the Na’vi and seeing the humans as the technologically superior invading force. Well, we got to make them bad ass, right?”

From The Abyss to Titanic to the underrated 2011 cave diving thriller Sanctum (which he produced), not to mention his various documentary projects, Cameron is more preoccupied with undersea exploration than any filmmaker in history who’s name isn’t Jacques.

That preoccupation reaches its apex in the second and third Avatar movies, so I asked him what it is about the ocean that keeps him coming back to it to tell stories.

“There’s something wondrous about being underwater, whether you’re on scuba or whether you’re doing breath-hold diving, which I also love. So, yeah, I’m just trying to capture that and convey it. We don’t want everybody in the world to go jumping in the water. They’ll mess it all up.”

“I do it on the fictional side and I do it on the documentary side. After I did Titanic, I took about a seven-year sabbatical and just did deep ocean exploration. Didn’t do anything else. I mean, I had a TV show going in the background [Dark Angel], but I wasn’t directly involved in that.

“I love going deeper. I love seeing things nobody’s ever seen. I love building hardware to go do that. And then it came full circle after Avatar‘s success. I did two things: I wrote the sequels that involved the ocean clan, so that I could create a whole ocean ecosystem with lots of really cool creatures, and obviously the Tulkun, which become… they sort of take over from the mining and extraction part of the story of the first Avatar for being the part of Pandora that’s at risk now from ocean extraction, if you will.”

“It’s thematically dealing with things that are really happening in our world in a way that I don’t think is particularly coy. I think people get it. It’s pretty on the nose, and it’s meant to be. Even after the first Avatar, it took two years out to go to finish building a sub, and go to the deepest spot on the planet. So I’m never going to be very far from that, in my thinking.”

This close relationship with nature is another way in which the Avatar movies channel Māori values.

“I think that the spirit of what it is and the feeling it conveys is very palpable,” Curtis told me. “It’s difficult in the society we live in to convey the sense of emotion that Indigenous peoples feel towards land. It’s not something that’s easily understood through buying a parcel and defining it on a map. It doesn’t really translate well in the in the modern world. But what Jim’s created is where those lines on the map are still being fought over and still are yet to be defined. I think it really connects, really resonates for me really strongly, in terms of an Indigenous view of nature and our world.”

“It doesn’t quite align with how we have to live to survive in our current society. But I think what he’s done beautifully is create a context where we can explore these things emotionally, rather than cerebrally.What it’s like to feel so connected to your land or your sea or your islands or your culture or your songs. The [Tulkun], they’re obviously Māori to me, but Jim will have his own point of view. These creatures are inspired by us, but they belong to Pandora.”

Watch the full James Cameron interview: