One man’s very subjective list of their favourite music docos

If one thing is true of music docos, it’s that there literally cannot ever be enough.

Forget objectivity, Tony Stamp’s here with a personal take on his fave music documentaries.

It feels like peak music doco season right now. Todd Haynes doco The Velvet Underground is about to hit Apple TV+, over on Neon you can revisit the chaos and disaster of Woodstock 99: Peace, Love, and Rage, Questlove’s superb Summer of Soul is a recent arrival to Disney+, and over the past few months we’ve seen new music doco series by Mark Ronson, Paul McCartney and Rick Rubin, and others. And if that wasn’t enough, Peter Jackson’s The Beatles: Get Back is on the horizon.

Look, if one thing is true of music documentaries, it’s that there literally cannot ever be enough—so, in the spirit of this, here’s Tony Stamp with his personal faves.

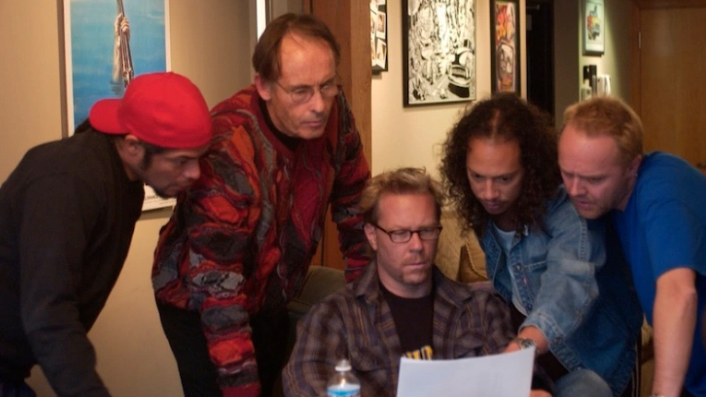

Metallica: Some Kind of Monster

Metallica: Some Kind of Monster

Chronicling two years in the life of heavy metal titans Metallica, this 2004 doc steers dangerously close to mockumentary territory, particularly in scenes involving the band’s “performance enhancement coach” Phil Towle—a man assigned to the band by their management, who is neither a trained psychologist or psychiatrist. After one (9 ½ hour) meeting with Towle, bassist Jason Newsted quit the band, leaving them to hunt for a new one in the midst of recording their album St Anger.

The film also covers their legal battles with file-sharing pioneers Napster, singer James Hetfield checking into (and out of) rehab, and lead guitarist Kirk Hammett getting told the new album won’t have any guitar solos. It’s a fascinating look at warring egos within one of the world’s biggest bands, and the tension between art and commerce on a giant level. It’s also very funny.

Amy

I wasn’t too familiar with Amy Winehouse’s music when I first watched this 2015 doc from director Asif Kapadia (the man behind the recent musical docuseries 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything), but this intimate, mostly non-judgemental film was the window through which I came to love her.

Posthumous docos can be somewhat fraught if they feel too much like vultures picking through an artist’s legacy, but Amy feels affectionate, and thoroughly competent in the way it presents her story. Disembodied talking heads narrate the film, including, crucially, her own, as well as her former manager, ex husband and various family members.

At times it feels a bit like a horror film as we watch this young, phenomenally talented person succumb to drug abuse (repeatedly), but Kapadia’s intentions are good in telling this cautionary tale, and it’s made clear that Winehouse fell victim to a vast industry with inadequate safety nets. More importantly, her music remains the focus throughout.

Scratch

As a young man beginning to dabble in music production, I was excited to see Scratch at the 2002 NZIFF. For the newcomer it provides an entry point into the elements of hip hop—MCing, graffiti, breakdancing, beatboxing, and DJing, and eventually focuses on that last one, explaining scratching, turntablism, making beats, and how several generations of musicians pushed the boundaries of what can be done with some vinyl and the right gear.

Luminaries like Mix Master Mike, DJ Shadow and DJ Qbert act as guides along the way, explaining how the turntable became a musical instrument in its own right. A line is drawn from the birth of the artform in the 1970s to a possible future, and twenty years on, it’s still enlightening. As Qbert says, “It’s like you’re the instrument, and the universe is playing you”.

The Chills: The Triumph & Tragedy of Martin Phillipps

The Chills: The Triumph and Tragedy of Martin Phillipps

Very near the start of this 2019 character study, Martin Phillipps goes to his GP. The camera lingers in closeup on his face as he’s told he needs to stop drinking immediately, or he’ll die. It’s an incredible moment to start a movie on, and Julia Parnell’s film doesn’t let up after that, chronicling Phillipps’ newfound sobriety, his history of hoarding (at one point he spray paints a mummified cat for an art exhibition), the extremely high degree of turnover in his band (there have been at least thirty former members, some of whom appear on camera and are none too complimentary), and the fact that he wrote (and still writes) wonderful, perfectly-formed indie pop songs.

Special attention is paid to Dunedin as well, which remains an incredible hub of local talent, particularly for those with vaguely gothic inclinations. It’s nice to see it captured so beautifully on screen.

There are dark moments, but the film mostly serves as a celebration of Phillipps’ eccentricities, ending on a note of optimism with the future of the band looking rosy (the current lineup is by far the longest standing), and Phillips back in good health.

Dig!

The Brian Jonestown Massacre and The Dandy Warhols are two bands I like a lot (with some caveats—anyone who saw the latter’s disastrous, too-stoned performance at The Big Day Out 2004 will understand).

Filmmaker Ondi Timoner doesn’t seem too concerned with their musical output however, instead focusing on the rivalry between bands, and the idea that Anton Newcombe, who leads the Jonestown Massacre, is one of those creative geniuses that pisses everyone off. There’s the sense that his band is the real deal, and the Warhols are fakers chasing their coattails—one notable scene has the latter showing up with a photographer in tow the morning after Newcombe and co. throw a party, posing as if they were part of the debauchery.

According to Warhols’ frontman Courtney Taylor-Taylor, Timoner took eight years of footage of The Dandy Warhols, and a year of The Brian Jonestown Massacre, and spun it into a narrative, but honestly part of the fun here is trying to figure out who’s being honest and who’s protecting their legacy. Bruised egos abound, and it’s bloody good fun to watch.

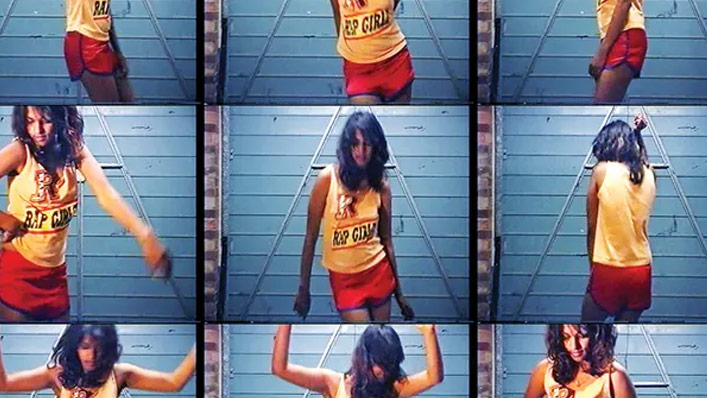

Matangi/Maya/M.I.A.

Director Steven Loveridge is a longtime friend of Mathangi “Maya” Arulpragasam, better known by her musical pseudonym M.I.A., and so was granted access to twenty years of her personal footage for this intimate doc. He aimed to humanise a star he felt had been somewhat demonised by the press, showing glimpses of her adolescent relationship with her father, a Tamil Tiger, through to the fallout of her flipping off the camera at the 2012 Superbowl, and her continual frustration at being taken out of context in interviews.

I’ve seen reviews of the film who think she comes across badly, but I found the film hugely sympathetic, a portrait of someone torn between two countries and trying to use her position for good. There’s not as much music as I’d like, but what’s here is great, particularly when she digs back into her earliest demos and we hear that her unique style was 100% crystallised before she ever signed a record deal.

Swagger of Thieves

Alternating between tragic and triumphant, this long-in-the-making portrait of Wellington gonzo-metal band Head Like A Hole follows them into middle age, giving particular attention to singer Booga Beazley and guitarist Nigel Regan as they continue to pursue a rock n’ roll future, haunted by intravenous drug use of the past.

We meet Booga’s partner Tamzin, doing her best to keep their family running, and a clutch of disgruntled former bandmates, as director Julian Boshier is given all the access he could want. To call it ‘warts and all’ would be an understatement, but the heft and yes, swagger of the band at the height of their powers is undeniable.

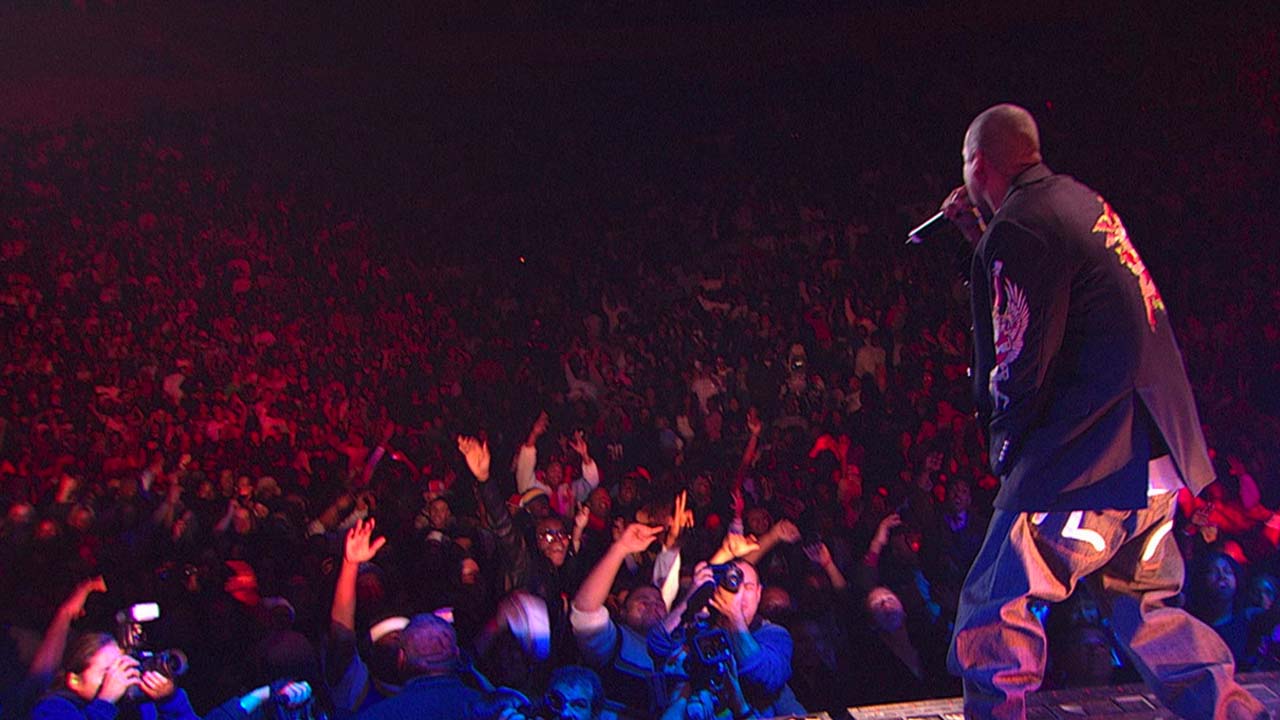

Fade to Black

Documenting the recording of Jay Z’s Black Album, this one left a handful of moments etched in my mind: producer Rick Rubin inviting The Beastie Boys’ Mike D into the studio as they both marvel at Jay doing all his raps off the cuff with no notes. Timbaland pitching beats while swigging from an enormous jug of juice. The way Jay snaps into focus when he hears a rhythm he likes, like a man possessed.

He’d announced plans to retire from the industry after the Madison Square Garden performance the film leads up to, which evidently didn’t pan out—he’s released two more albums since then, as well as collaborations with Kanye West and his wife Beyoncé. But there’s still a sense of finality or importance hanging over the movie, even if everyone looks very babyfaced nearly twenty years after the fact.

Mostly I continue to enjoy it as a look behind the scenes at how hip hop albums are actually made, capturing the unique chemistry between rappers and the producers supplying them with beats. I’m happy to see many of these moments live on, in gif form.

Instrument

Fugazi are still one of my favourite bands, and in my twenties they felt completely untouchable—innovative, noisy, channelling an energy no other band seemed to have. I didn’t know much about hardcore music, and there was always something foreign and alluring about them. Even more so this film, which was filmed over ten years and edited over five, consisting of concert footage, studio sessions, and interviews with the band.

It’s definitely one for the fans, abstract and scattered, but for those inclined it’s politically enlivening, and jam packed with electrifying live performances.

Kurt Cobain: Montage Of Heck

This one comes with a huge caveat. The filmmakers trawled through Kurt Cobain’s journals and personal footage, and included some things I just don’t think should have been revealed to the public, including animated recreations of Cobain’s childhood. It can feel very icky, and more than that, unnecessary.

BUT. Nirvana wrote some fucking good songs, and the elation I feel every time I hear one is still very much there. For context, I was fourteen when Nevermind came out, and to call its effect on me ‘formative’ would be an understatement (me and an entire generation of disenfranchised white kids). So maybe I’m an easy mark, but all the footage here of the band making music and performing makes it a must-see. For a brief period of time they were untouchable.