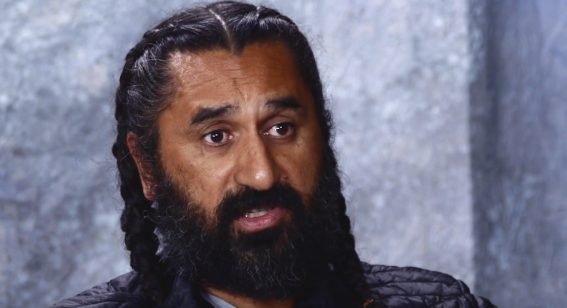

“Our ancestors were smiling on us”—the epic planning that went into Vai

We were very, very lucky.

Vai, the latest from the producers of Waru, tells eight stories about one woman’s journey of empowerment through culture. Each portion shows a different period of her life, told in real time, and directed by a different female Pasifika filmmaker.

The film “lands as a bold experience that rightly highlights the need for more Pasifika cinema” Flicks writer Liam Maguren declared in his review.

With the film now in cinemas (find times and tickets), Flicks talked to producer Kerry Warkia about the hard work that went on behind the scenes, the importance of constant communication, and the dumb luck that helped the film get made.

This interview is edited for length and clarity.

Flicks: Given all the locations involved with making Vai, was it more demanding on you as a producer compared to Waru?

Kerry Warkia: They definitely both had their challenges but I think this was way more demanding in terms of the scope of budget and of the travel that went along with it. Even though we only actually had eight days shooting for all of the films, we had six weeks of travelling. And that was back-to-back, so that was huge.

We were also taking care of all of those people and the tikanga (protocol) for all of the different cultures, making sure that we were respecting that, giving enough time to our local crew and teams and in many cases villages to participate and be really comfortable with the filming. And I think that speaks to the strength of the connections that all of the filmmakers have back home, and how beautiful that was to witness and be part of.

Was there any major lesson from making Waru that you learned and applied to this film?

Yeah—how we can always improve on communication. That’s a huge thing. But also how important it was to have a budget that really allowed you to do all of that communicating, that allowed you to be in places talking to people. I think that was our biggest lesson, was how do we take care of people holistically. That’s something we really tried to do anyway like with Waru, how do we create a space for all these female directors to reach their potential? I think that’s really important.

On Waru, we were able to bring children to set, we were able to make all of that happen, and support them that way. Unfortunately, towards the end, because we had such a low budget, it was really hard to keep that going. Into post-production, it was hard to be able to go, “Yeah, I’ll just fly to you and talk to you.” Some conversations you have to have in person because the stories are personal. Email or over the phone doesn’t do it.

That was something that we really learned and something that we took into Vai, being able to be where we needed to be and be there in person, and for our scout to be able to go into villages and talk to people, and really make sure that we had a personal connection.

Are you sick of flying?

Look, the long-hauls kill me so going to Berlin and back again, even though it’s wonderful, it’s exhausting.

Going to the islands, there’s a completely different feel. The flights are much shorter but it was pretty tough, I think, on everyone because it’s literally: we landed; do the cultural or traditional greeting that either the villagers had prepared for us and that we would help facilitate or we would have a meal with all of our local crew and meet everyone and say thanks to everyone in order to start the process; the next day would be a full rehearsal day; the next day was the shoot; then you’re pretty much on the flight—sometimes the same day as the shoot. So that was pretty taxing.

It was a really tight schedule, but I’m actually really, really super proud of it because we pulled it off. Anything could’ve gone wrong at any time, but our ancestors were smiling on us.

One of the days, we were up at 4:30am to get the shot we needed because we were on the plane at 10:00am. We were very, very lucky.

How did you all coordinate to assemble this timeline of a life?

What [co-producer] Kiel [McNaughton] and I did with Waru and with Vai was build the framework, the writers and directors could step inside that framework, and then we had a five-day writers’ retreat. The framework is non-negotiable.

During the writer’s retreat, we’re essentially all mapping out her life together and those stories are incredibly individual to each of those writer-directors, where they’re from, and what they wanted to say with their individual piece as well as holding what we wanted to say collectively.

Did the filmmakers have to pick an age out of a hat?

That was one of our fears. Kiel and I were like, “Are we all going to end up in an argument over who gets what age?” But actually, I think a lot of them came with a lot of different ideas about what they could do, but also having in the back of their mind a place where they might fit with this woman.

It was really beautiful in terms of how that happened. Some of them said, “We’re feeling very strongly that we’re really attracted to this age in her life.” And the others would say, “Yeah, we think that’s beautiful that that’s where you want to fit and that’s what you want to speak to.” And I think one director said, “I feel really confident that the story that I need to tell will come once everyone else is comfortable where they sit, and I’ll slot into that space.” She was really gracious in that way.

One of the conditions in Waru was that each short had to be one shot. But in Vai, some of those break that convention. Was there a particular creative reason for that?

Most of them are one shot and then we have two that have edits. We said, “One take… if achievable.” But we also needed to be really flexible with making sure we could shoot it in one day. If that meant we had to put a cut in, whether it was a “no-cut” cut or an established cut (a meaningful cut that you can see), we were happy to do that because we didn’t want to have gone all that way and then not achieve it.

For example, with the Cook Islands short, she travelled on the road. And I don’t know if you know the Cook Islands or not, but there’s literally one road—we could shut down the road for, like, half an hour and that’s it. So we had to work with some of the constraints within our environment and make sure that each of those directors were still able to achieve shooting in that one day, and what they needed to get for their story.

What ended up being the most complex short to make?

They all really had their challenges—even if one of them was in one location. With Solomon Islands, she’s literally in the canoe until she dives into the water and you kind of go, “Great. That’s one location.” But when you look at it, you go, “Right, so we need to find the location where there’s also a wreck under the sea, we need to build a platform in the ocean so we can have the camera on it, and the camera needs this big arm to come out so that it can go over the top of her.”

With Niue, it was, “Right, now she’s getting into a truck and we have to film her up the truck. So what’s the plan for that? Because that all has to happen in real time.”

In Samoa, we were asking the whole island of Manono to let us film and potentially have the run of the island for two days.

Even with Fiji, we have one location but she’s running in and out of the house, in quite difficult spaces. And we have a little girl who’s the lead and she has to do that for one take. And we have rain that needs to happen at the end. I mean, they’re all complicated.

On the flipside, was there any one short that ended up being easier to execute than you initially thought?

NZ-born Samoan Vai, that’s Amberley Jo Aumua’s short set in an Auckland Unitec building, I was thinking, “She’s going up and down all these stairs and corridors, and we have so many extras, this is going to be very, very complicated.” But we had an incredible 3rd AD team—three of them—and they absolutely controlled the extras coming in and out, and they were really, really proud of their job. And I think that’s one of the things that I love about filmmaking—everybody really wants to do the best they can in their role. And that ties in the whole.

I also thought it would have been tough on the actress, but all of these actresses were incredible and only one of them is trained—all the others have never acted before.

[Aumua] ended up doing 21 takes, which was pretty incredible. That was the record.

Is there anything you could reveal that’s happening next with this collected short stories format?

We have a third that’s in early development at the moment. And that one is called Kāinga. And we would like to make that in collaboration with Kiwi Pan-Asian writer-directors. That’s the next one in our sister films.