Season 2 of Yellowjackets crystallises its themes of trauma and regret

We’re all drowning in content—so it’s time to highlight the best. In her column published every Friday, critic Clarisse Loughrey recommends a new show to watch. This week: the continuing saga of survival, supernatural visions, and show-stopping Melanie Lynskey monologues in Yellowjackets.

There’s a bit of dialogue in Yellowjackets that’s been haunting me for the past few days. I devoured season one, and the first six episodes of season two (those provided to critics), in the span of a few short days. So I can’t even remember who said this, in what context. My notes came up with nothing—at the time, apparently, I didn’t even register it as significant. I may not even be remembering the exact wording quite right.

But still, I can’t stop replaying the phrase, said as a plea so profound and desperate that it produces its own echo: “I was a good person before all this”.

The series follows the members of a girls’ varsity soccer team from a high school in Wiskayok, New Jersey, whose plane crashes in the Canadian wilds en route to their national championships in 1996. The survivors were forced to live out there for 19 months. What they did, and what they lost, remains a secret. Not only is the truth fiercely guarded away from the outside world, but it’s seemingly unutterable even in total privacy.

And these girls—they were good people, to the extent that most people are when they’re young and in their prime and full of promise. You hear a lot of talk about how hatred is taught. What Yellowjackets has more adventurously decided to tackle, and which crystallises in season two, is the idea that trauma itself can fundamentally alter a person’s soul.

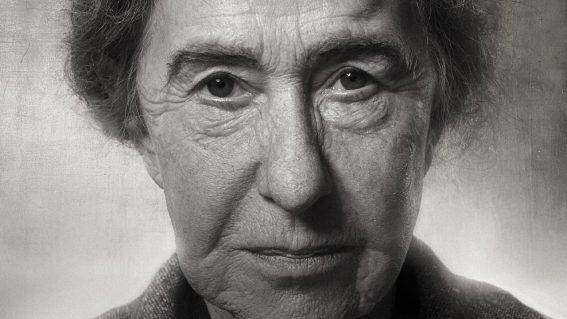

The series flashes back and forth between the aftermath of the crash and the present day, in which those we know who survived—Shauna (Melanie Lynskey), Natalie (Juliette Lewis), Taissa (Tawny Cypress), Misty (Christina Ricci), and, as introduced in season two, Lottie (Simone Kessell) and Van (Lauren Ambrose)—attempt to flee their own pasts.

There’s certainly an element of dark comedy to Shauna’s not-entirely-on-purpose murder of artist Adam (Peter Gadiot), who she ended up having an affair with last season, or Misty’s kitten-sweatered sociopathy. But, in these new episodes, spread out both in scenes of past and present, is a deep, heart-wrenching sense of mourning. These women are cursed: yes, perhaps by the antler-crowned spirit that does or does not linger amongst the trees, but more importantly with the perpetual “what if” of who they could have become had they not been forced to experience the unfathomable.

I can absolutely understand why some critics are starting to grow tired of the Lost-esque mystery of Yellowjackets—the question of whether the supernatural events we see are real or a collective hallucination. But I think there’s also something brutally effective about its use as a metaphor. Trauma, to these women, is more than a feeling locked deep in their chests. There’s a shape and a dimension to it. It’s able to live outside of them because it is not, they know, fundamentally who they are, but it has enough strength to shape their destinies.

Throughout season two, we see how these survivors fall into patterns of superstition and delusion, not because there’s something fundamentally weak about them, but because we are inextricably bound to our desire for hope. “We’re gonna need more than food if we’re gonna survive this winter,” Travis (Kevin Alves), the coach’s elder son, tells his fellow survivors. There is no living purely for living’s sake.

It’s always a little complicated when pop culture decides to blend the topics of the supernatural and mental health, and Yellowjackets’ depiction of schizophrenia and dissociative identity disorder is certainly flawed. But I think the larger aims here are so well-intentioned, and the characters are treated with such empathy, that the series has allowed itself a certain freedom to push its “are-they-or-are-they-not cannibals” carnival of horrors without devaluing itself as a psychological portrait. It certainly helps when you have actors as talented as Lynskey, who delivers not one, but two showstopper monologues in the first six episodes alone.

I’m not sure where exactly Yellowjackets will head in the two episodes that come after, but I already feel so ingrained in these women’s lives that I can’t wait to find out.