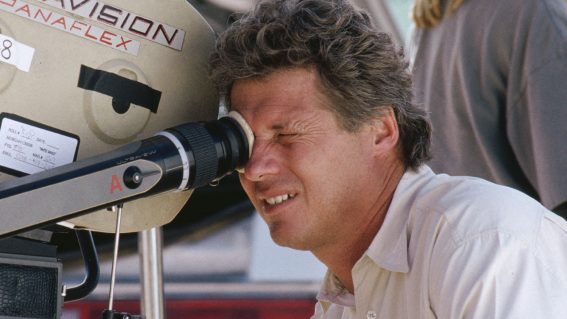

Vincent Ward on the 30th anniversary of Palme d’Or-nominated The Navigator

In-depth interview with the director of this ambitious, visually striking masterpiece.

It’s been thirty years since the release of Vincent Ward’s Palme d’Or-nominated masterpiece The Navigator: A Mediaeval Odyssey.

Ambitious, idiosyncratic, and visually striking, Ward’s film captured worldwide attention. The director looks back on its production and release here with Flicks Editor Steve Newall.

FLICKS: What did you think was possible within the international film landscape when you set out to make ‘The Navigator’ and what were your initial aspirations for the film?

VINCENT WARD: What I think from this perspective is, I was incredibly lucky in that phase.

I think things have become more brutal and pragmatic in the current climate because it’s much harder to release independent films – it’s much more expensive and the market has really shrunk. Whilst obviously there are people who have made it work, by and large, it’s definitely a lot harder and a lot less adventurous, the climate now, with tentpole American films being the main staple of what’s released.

Or, in New Zealand and Australia, independent style of films for the female demographic of over 40 and older. It’s sort of really narrow. And films are being really made for about the same price, in terms of what you can raise, for not that much more than what we were raising back in the late 1980s. Even though costs are many times higher – 400% more, probably.

I think what’s happened, as a result, is that everybody has become a lot more pragmatic. I was lucky to work with, at that time, producer John Maynard. He’d come from an art school background and totally believed in directors and really was prepared to back me in the way a patron backs you in the sense that he didn’t interfere with the story or what I had in mind. He went, “Wow! Let’s give it a try, and I’ll give everything I can to make it work for you, Vincent.”

When I look back, not as a self-obsessed filmmaker, which possibly I was at that time (I don’t know – it’s something you need a certain amount of to get stuff across the line), but as somebody who realises how difficult films are to make… The main thing is that he was a person who managed to allow and support with incredible pragmatism and inventiveness.

We had a film set in the Middle Ages in New Zealand with the impression of moderately extensive sets. A boat on water with a horse in it. Just things that were a little bit out of the normal league of an independent film.

At the end of the process, I got called in to see Steven Spielberg in LA, and he was asking me how we did it. Even though I was an hour late to the meeting because I lost my way, he took the whole meeting and spent 45 minutes standing as I talked and answered his questions.

I think it would be almost impossible to do that film now. At that time, also, you had people like Lindsay Shelton at the New Zealand Film Commission. They had their own sales agency, which was terrific because it meant they undertook to back a film and release it, and it wasn’t the more obvious choice of film that they would back, because an international sales agent is normally only going to go for a safe bet.

The Film Commission, if they believed in you, would actually back something completely idiosyncratic.

They’d actually go into the market at the sale of the film and sell it for you. You didn’t need that huge structure or that dependence on someone you don’t know who’s an international sales agent in the hope that they might buy into it.

When you came to make ‘The Navigator’, you had a bit of filmmaking capital under your belt, metaphorically, because you’d worked with John on ‘Vigil’ already. Were you spending all that filmmaking capital as courageously as possible?

Yeah. The Film Commission didn’t want to do it. I mean, imagine if I walked into your office, and you were at the Film Commission, and I said, “Look, I have this great idea. It’s about a bunch of guys who burrow through the earth in the Middle Ages and wind up in Auckland, New Zealand.” You’d kind of go, “Yeah, what are you smoking [laughter]? Get out of here.”

Whatever one’s current capital is, it’s an unbelievable leap of faith. The assessments the Film Commission did came back and raved about the script, from people we didn’t know in some cases.

But winding back to the beginning of the process, the Film Commission initially didn’t get it at all, by and large. Then a few people that were, I guess, on the board, and based on the assessments, thought, “Wow! This is out there, but it’s really interesting [laughter]. And Vincent had some good credits.” I had three really good credits in terms of films that had won film festivals – A State of Siege, In Spring One Plants Alone, and Vigil – and John’s tremendous drive and passion.

That’s what amazes me. Once I’ve made a film, I kind of detach from it, and it’s something in the past, but what amazes me more is the other people around it that enabled us, that allowed that film to happen, because we operate in an industry which is almost impossible to survive in most of the time, and you’re really, as I always say, only as good as those people that enable you or have faith in you.

When you’re trying to convey this vision you’ve got for the film and get people behind it, you’re working from a script. Is there anything else, any other supplementary stuff, to help convince people that they should’ve been backing such an idiosyncratic idea and style?

Well, let me explain a couple of things about it.

Basically, there was just the script and then a lot of drawings to do with how I envisaged it. We got it nearly financed, it looked like it was going to be made, and we started filming. We just had one investor that hadn’t quite been closed, and then – I don’t know – the tax law changed and suddenly it fell over. The deal fell apart. I was heartbroken. The rest of the crew and I was in tears. Man, I just cried because I’d spent years on this project.

John and I left New Zealand and John vowed never to return except to visit. He vowed never to live here again. We went to Australia and I lived in a kind of broken down flat in Kings Cross – where a close friend helped me out. The Cross was colourful at that time and the flat had the usual thing at that time with several people skimming past addictions but I just kept my head down, ignored the immediate place apart from a few friends that helped me through it and quietly kept working on my project.

John kept trying to raise money out of Australia and eventually he succeeded. It was the first New Zealand-Australian co-production and one of the few features that had been done as a co-production with Australia. We came back to New Zealand a year later.

So, to answer your question, the Australian Film Commission sent one person in to look at this, to talk to me, and they were a visual effects person, because they weren’t sure whether I could do visual effects, which is ironic given the visual effects Academy Award that What Dreams May Come won years later. I’d mapped it all out, drawn it up, worked out how all the effects would be done, and consulted with the people, with the visual effects supervisor in Australia, and that convinced them that I knew what I was doing. So that was one of the hurdles for us, too.

By the time we came back to New Zealand, the package was together. New Zealand was only a part of that much larger package, and so it was pretty hard for people to say no at that point.

How hard was it for you to get the determination to actually persevere with the film after it fell over? Or did you become absolutely determined it was going to happen?

I think it was John again, his determination. He’s the nuggety son of a bookie from Southern Victoria. He used to bicycle across town with the bookie money that he had to deliver or pick up for his dad when he was a kid. So he was, although very cultured, very streetwise as well, and lives with this sort of determination now. He would not let some shitty tax law and some people with a complete lack of vision beat him.

And he was very honest, so he didn’t allow anybody to go unpaid. He made sure that he pulled the plug before we were in debt. So very astute. I had a vision for what the film could be, but it means nothing unless you’ve got the money to make it.

There are many technically ambitious shots and sequences. How challenging was it to pull off some of the water-based stuff and the high-altitude shoots? And how difficult was it for you to maintain a production where everyone was confident that that was going to work?

What I’ve noticed over the years is that many of the worst films are the smoothest shoots. People come back with stories of how great a film’s going to be – crew from a shoot – and normally they’re wrong. By about three quarters of the way through, pretty much everyone has lost faith in it.

Not John. Not me. Not a number of my actors and my co-writer. We all believed in it and some of the key crew obviously were really passionate about it, including our DP Geoff Simpson and the production manager Godfrey Hall. He was always passionate about it. But a lot of people just thought, “Oh, too many challenges. Too out there. It’s going to absolutely fail. It doesn’t stand a chance.”

It was strange because we were often working in a climate where there was a fair bit of negativity, and many things go wrong on a shoot. It’s just inevitable, particularly one with ambition and freedom with the resources.

Fortunately, all the main things went right. And things like safety, well, I’ve never ever had issues with safety. I’ve always been very careful. Even though we filmed at the top of the Southern Alps for two days in waist and neck-deep snow, landing by helicopter and ferrying out by helicopter, and even though we attempted a number of challenging things, there were a lot of areas where the film is quite contained.

I think the biggest killer was just filming night after night, and night shoots. It’s very hard on people to take that body-change of rhythm and work those hours, where you just get incredibly tired and worn out.

I was really lucky. I had a fabulous production designer, Sally Campbell, from Australia. I had a wonderful special effects supervisor, Paul Nichola. He solved those different special effects really inventively with a tiny budget for what we were undertaking. John always made sure that we kept on track, that inventive solutions were found rather than expected solutions. Even building a nuclear submarine out of wood in an ex-sewerage pond – which of course was water-tested to make sure it was safe – rather than use expensive water tanks, or building the fake part of the top of a cathedral. Somehow, we managed to do that.

I’m not quite sure how, but somehow we did [laughter].

The submarine sequence in particular. I understand why, in that Spielberg meeting, he asked how you did it because it’s still an audacious kind of mystery to watch.

Well, particularly when you consider the submarine was made of plywood. It didn’t move at all. It was in water that was about a metre and a half deep, so you had to create the illusion of a moving submarine. It was accidentally built about half a metre higher than it was meant to be above the water, and we had different gangs of roaming thugs that were wandering around the set when we weren’t there and trying to destroy it. Even the security guard was beaten up one night.

Once you had the finished film and audiences around the world started getting the opportunity to see it, does it come as an advantage taking it overseas that it’s a New Zealand film, but you don’t need to have any knowledge of New Zealand, really, to watch the film?

Well, it’s a myth, isn’t it, really? They’re kind of universal stories, and in this case, a very human story of betrayal by a brother and an adventurer seeking something, a myth-like adventure in some ways.

But New Zealand is at that stage that we’ve had a real cultural cringe, and the only way that it could’ve succeeded in New Zealand – because it was out there – was if it succeeded first overseas. And we were lucky. It went to Cannes. It then won three international festivals, many other awards and we cleaned up at the Australian Film Awards as well as the New Zealand Film Awards.

It was hard to argue with that in terms of its publicity leading up to it leaving New Zealand. It was on a roll.

That’s the kind of ammunition you needed to have around that period, isn’t it?

You did at that time, yeah. Now it’s more complicated.

Say you have a film in Toronto. It just takes one reviewer online to say they hate it and then everybody picks up on it. I haven’t had this problem, but I understand people have. I got, by and large, extremely good reviews on The Navigator. The reverse strategy, in some cases, may apply now as opposed to then because of the internet.

I mean, if you get it wrong, and one reviewer dislikes it, and it happens to be the first review out, then it can cause you a lot of problems even though it’s atypical.

I found it interesting revisiting ‘The Navigator’. There’s a whole set of very contemporary issues that are in the film. There’s the spectre of nuclear holocaust. There’s the spectre of HIV looming over it. But in 2018, there’s a whole bunch of different issues that you can bolt on to review it, really well.

Do you think that speaks to the fact it is a successfully told myth, that it is applicable to things that aren’t just what you wove into it at the time?

That’s what a myth does. A good myth transcends time, like Gilgamesh, written in 2100 BC, then popular for more than three centuries, inscribed on pillars in many countries in four different languages, and lasting longer in its shelf life than any film we’ve ever known. That’s the ultimate in a successful piece of storytelling.

That’s what you hope for. That it’s good mythic storytelling that’s anchored in the behaviour that perhaps is something that you hope will transcend time and connect with people in different countries.

It’s very obvious to consider now in 2018 while watching the film, but it’s a film about refugees, and that was the very obvious thing that I kept relating it to as I was watching it. There’s always going to be stories of people pressured to leave their homes, to do something to make life safer or better for themselves.

My mother was a refugee. She arrived here after the war and had just married my father, so I certainly identified with refugee scenarios. My father was of Irish Catholic descendant. Obviously, there aren’t too many stories from the 19th century that mix in Ireland that have a happy ending. In fact, I don’t know of any. So the two cultures that they respectively came from very much carry strong narratives to do with forced migration. That’d make sense because that’s all very much a part of my conscious.

It was the second film that you had taken to Cannes and I imagine that experience is no less daunting the second time around, but what were you expecting when you returned to Europe with the film?

I’m also curious about what else were people getting excited about at that festival as well as ‘The Navigator’. What was the environment like that you were getting into?

I remember there were two of us younger filmmakers there at the time. Lars von Trier and me, because we did photo opportunities together and so on. There were a lot of more experienced, older filmmakers there, so I got to know people like Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog, and there were other well-known directors like John Sayles.

What was it like? In different periods, different members that are involved in filmmaking have the most significant say. In the ’80s, thanks to Easy Rider, made some time previous, that say was with the director’s voice. In other periods, later – I think, in the ’90s – it became the American agent. In other periods, it became star-led. In other periods, it became producer-led. Probably a little bit more now, it’s perhaps slightly writer-led as a result of series television.

But at that stage, it was director-led. That was represented in the types of filmmakers that were at Cannes, the sort of attention they got, and the sort of releases they got. That’s largely changed now because there aren’t release opportunities available unless you’re one of the few favoured, independent American directors, and really, literally, only a handful of them, unless you’re doing American tentpole Marvel garbage.

The climate and market’s completely changed. It’s so challenging out there for independent filmmakers, and acknowledging somebody as brilliant as Taika and other of our luminaries like Jane Campion or Peter Jackson, nonetheless now, out there most good independent filmmakers are finding it very challenging. And producers, too.

Are there lessons in the film in terms of either the filmmaking process, or just the very type of film that it is, that you think are relevant for other filmmakers to consider in the present time?

Well, it’s hard, really. I think the film is about hope. Call it faith if you want, but it was never meant to be about religious faith except narratively for that period of time in the Middle Ages.

I think that the only way you can make films successfully is if you not only believe in yourself – and with that, the supporters you have believe in you – but you have to believe in them. Even when people falter or have difficulty making a film, as a filmmaker, you have to consistently find a way to support them and give them some room to move so they’ve got participation in the project you’re making, and that’s not always easy.

At times, I doubted myself and doubted some of the people I worked with. But if I learned one thing from that film over the years in relation to filmmaking and every other endeavour I do, it’s that you need to believe in and make it work as much as you possibly can for everybody around you, whatever that takes.

Maybe I’m more the father now and having children changes the way you think and therefore you’re more nurturing, although I was moderately nurturing, and I was very enthusiastic at that time of my life.

How did your enthusiasm translate to the way the film was received? It was obviously door-opening, given the Spielberg meeting and later work on Alien.

I don’t know. You’re one sort of person at a particular time of your life and people come to you. I was never an outgoing person, so people tended to come to me, not the other way around. I got offered a lot of films as a result of that in America which I’d turn down, by and large, and ended up making Map of the Human Heart.

How do you feel about ‘The Navigator now’? It’s been associated with you for such a long time. It’s a standout film in your filmography.

In New Zealand, I’m known mainly for Vigil and perhaps a little bit amongst a smaller audience for Rain of the Children, which is the film I like most that I’ve made, but mainly because of the old lady in it.

Curiously, in a number of other countries, I’m mainly known in some cases for The Navigator, particularly Australia. It seems to really connect as a masthead flagship film for them. That’s what people associate me with in Australia, and people responded very strongly to that idea there. And certain other countries as well. So my attitude’s affected by, to some degree, what other people think of it.

But I’ve moved on. I’m in a different place now and I don’t dwell on the past. I have at times. I certainly don’t at this time in my life. I’m not really interested in looking in the rear-view mirror. Not anymore.

Is it difficult having a relationship with the films you’ve made in the past? It’s a relationship that must change a bit, right?

Well, how easy or difficult a experience was it of making it? Your feeling about the film is altered and tempered by the experience of it, either during it or after it, so you’re not objective because of the ease or difficulty of those experiences. I know that’s not a short and wonderful answer, but it’s the reality. Maybe there’s a more pithy and wonderful way of putting that. I’d have to think about it.

No, it’s insightful because we, as people outside the authorship of those films, associate filmmakers with projects. We’ll put brackets after your name and write the films there as references. You’re so attached to them, and I was curious how it feels to have those relationships with the art.

I’d be curious how people like Spielberg think of Jaws now, because obviously that was a cow of a film to make, a terrible experience for them, but then it had this amazing release. Or people like Herzog. He’d go to film a volcano expecting it will erupt because it’s started to erupt, and gets there and nothing happens. So everything’s tempered by our experiences of the journey in making and releasing.

This story is part of our month-long celebration of 40 years of NZ film. Follow all our daily coverage here.