A soaring and heartful telling of Dame Whina Cooper’s life, Whina is a triumph

A powerful portrait and also a breathtaking picture of nearly a century of social history.

Aotearoa biopic Whina charts the life of iconic Māori leader and activist Dame Whina Cooper, brought to life on screen by Tioreore Ngatai-Melbourne, Miriama McDowell and Rena Owen. While the film is a powerful portrait of the woman at its heart, it is also a breathtaking picture of nearly a century of social history, writes Rachel Ashby.

When the screening of Whina I went to came to an end, there was a total silence in the packed movie theatre. It’s a magic thing to be in a crowd awed by storytelling, to know you have all just collectively watched something very special.

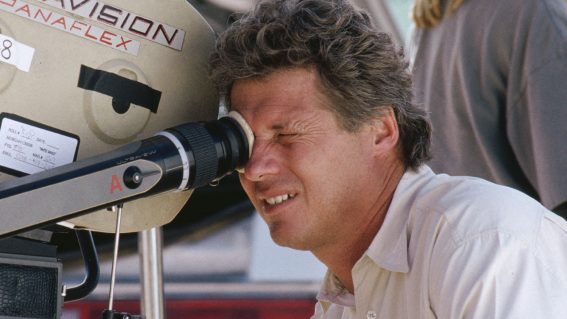

Directed by James Napier Robertson (The Dark Horse) and Paula Whetu Jones (Waru), Whina is a triumph. A soaring, heartful telling of the life of Dame Whina Cooper, Te Whāea-o-te-Motu, a leader and activist who fought ceaselessly for Māori and their whenua. It’s a monumental story to bring to the screen and one that has rightly taken many hands, and many years to achieve.

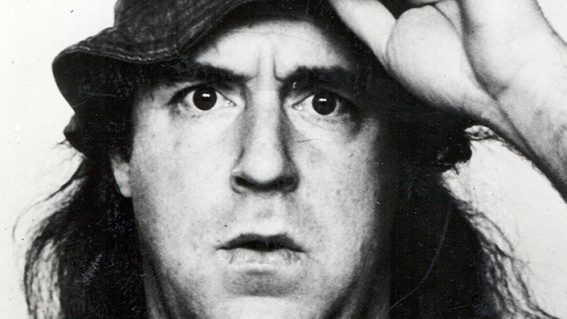

Three wāhine toa take on the hearty job of portraying Whina across her life, each rising masterfully to the task. Tioreore Ngatai-Melbourne is a ferocious teenage Whina, while Miriama McDowell carries the role of Whina as a young woman through to middle age with grounded resoluteness. The singularly challenging job of portraying the 80-year-old Whina, the well-documented and iconic leader of Te Rōpū Matakite o Aotearoa and the 1975 Land March to Parliament, is expertly handled by the legendary Rena Owen.

It is a huge role to take on, and all three actors have spoken about the particular ways in which channeling Whina has affected them not only as storytellers but as wāhine Māori. Certainly, there is a gravitas to each actor’s portrayal of Whina that honours her enormous legacy without reducing her personhood. McDowell, who spends the most time inhabiting Whina on-screen, has some of the hardest personal moments in Cooper’s biography to grapple with: the death of two young husbands, displacement from her turangawaewae and an ongoing internal struggle with accepting her rangatiratanga. She brings an empathy and determination to her performance that anchors the story in Whina’s humanity.

While the film is a powerful portrait of the woman at its heart, it is also a breathtaking picture of nearly a century of social history. Time expands and contracts throughout the film, and the telling of its events is non-linear. By threading the tapestry of Whina’s narrative back and forward, it brings to the forefront the scope of change that occurred across her lifetime for te Iwi Māori.

As viewers we are left with the understanding that this story is as contemporary to us now as it is to those on the screen. Archival footage is used well towards the end of the film to underline this idea and break the fourth wall in a purposeful way. The sight of thousands of people walking over the Auckland Harbour bridge—a news clip from 1975 that I have seen many times before—brought me to tears. It is a reminder, if one was needed, that all of this is very real, very recent and still very urgent.

There is a hopefulness at the film’s core that echoes Whina’s own activism: a promise to keep pushing despite opposition, and a reminder to think of the generation that follows. In this way, the film feels like a wero. There is much work to be done, so how are we going to do it?