Jordan Peele’s Us fires up our synapses in its aftermath, producing tingling discomfort

There’s a lot more going on than in Get Out , notes Aaron Yap, impressed with its ambition.

Oscar-winning filmmaker Jordan Peele follows his debut feature Get Out with another critically acclaimed horror-thriller. Two parents (Lupita Nyong’o and Winston Duke) take their kids on vacation, but relaxation turns to tension and chaos with the arrival of shocking strangers at nightfall—strangers that look just like them.

There’s a lot more going on than in Get Out , notes Aaron Yap, impressed with its ambition—even if it is sometimes at the expense of coherence.

Thrillingly ambitious in scope but more conceptually diffuse, Jordan Peele’s follow-up to Get Out might compare unfavourably for those wanting a replay of the airtight provocations of that killer debut feature. No doubt, Peele remains engaged in pushing conversations around race, class and privilege through the muscular thrills of a pulpy genre workout. But with Us—a film crammed with beaming signifiers both pop and political, teasing mirror imagery that’s wedged between literal and metaphoric—he’s created a far more searching and challenging macro-level proposition.

Peele’s adroit, tone-shifting craftsmanship continues to be evident. The first-quarter home invasion scenario where Lupita Nyong’o and Winston Duke’s family are besieged at their Santa Cruz holiday home by feral, sinister replicas of themselves most recalls Get Out with its tense—and tensely funny—set pieces.

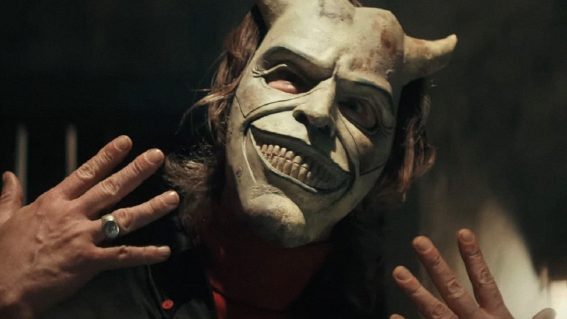

But the narrative morphs into something else entirely, embracing a deeper, somewhat baffling mythology that stitches together deadly doppelgangers, underground tunnels, white rabbits, ’80s activism and biblical passages. Fundamentally, it functions as a Trump-age Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but it’s also infused with the cautionary, disquieting apocalyptic air of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s J-horror masterpiece Kairo, another film about the subtly corrosive ties that bind us.

Yep, there’s a lot going on at the expense of coherence. Us feels, at times, like wildly inspired wackadoo gumbo leaking out of Peele’s brain after he’s given carte blanche. But even if the film doesn’t hang together in the moment as tightly as one might prefer, it fires up our synapses in the aftermath, producing the sort of tingling discomfort that arises when we realise how much of our awful present stems from our spiritual connection to the socially aggrieved.