Annie Goldson shares the personal journeys of New Zealanders in A Mild Touch of Cancer

David Downs and other Kiwis share their experiences with cancer – including an innovative treatment.

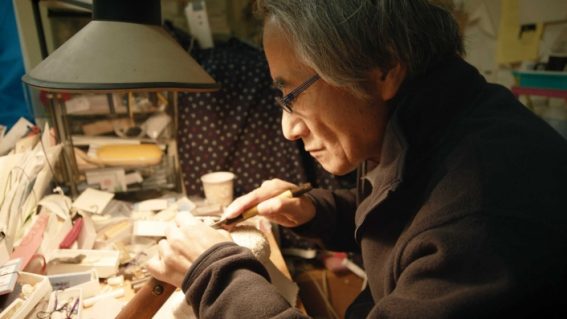

A Mild Touch of Cancer follows David Downs as he helps other New Zealanders negotiate their own journeys with cancer.

Director Annie Goldson (Kim Dotcom: Caught in the Web) brings the story of David Downs to the screen, sharing the story of the innovative cancer treatment that saved his life, and exploring the personal accounts of other New Zealanders with cancer. With A Mild Touch of Cancer about to play Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival screenings, Goldson tells us more.

FLICKS: Describe your film in EXACTLY eight words

ANNIE GOLDSON: If saved from dying, how do you live?

How did you come to know David Downs, and when did you realise you needed to share his story?

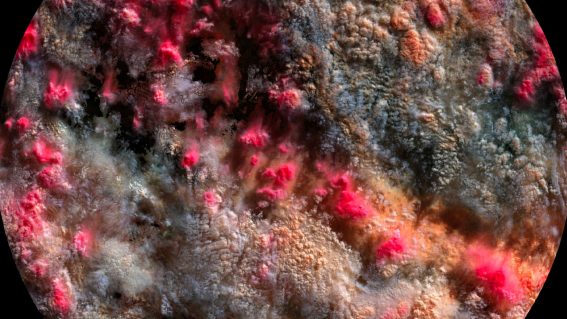

I was aware of David and his ‘cancer journey’ through his blog, which I found informative, funny and honest. A friend (and now co-producer), Irene Chapple, had done a short film about him and I thought the story had more legs. It has strong human-interest qualities but also could explore the science and history of an amazing cancer treatment, one that some are labelling a cure.

As I got to know David, not only did I find his back story interesting (and tellable because of his blog) but I also realised his ongoing commitment to others with cancer in Aotearoa would give the documentary unfolding observational threads. This I felt would highlight his generosity but also capture real-time dramatic stories and add diversity and variety to the documentary.

I do think the COVID outbreak has reminded us of the importance of decency, good science, the importance of family, whānau and community, those underlying themes that the film engages with.

Did you have a personal connection to any of the other people in the film before production started?

No–the script plan was to include others and their ongoing journeys, but I had no idea who they would be at the get-go. I was aware of the ‘postcode’ debates and the ethical issues that swirl around cancer treatments, ie who gets good treatment can be determined by wealth.

David, as a successful and well-travelled businessperson, was able to access the global science community and is well aware of that. But it meant he gave back in spades, and it was this generosity to others that allowed me to find our other characters, the Robins family, Kirsty Horgan and Mile Nafatali.

Did you learn anything over the course of this film that has changed your thoughts about the fight against, or acceptance of, a diagnosis?

I know, and understand, that people with cancer get very tired of the terminology of fighting and battling. This kind of language can make the person with cancer feel like they have failed if the disease progresses. To hear ‘palliative care’ is the only option is pretty tough which was more or less the position of all of our subjects.

I think what we saw was a determination, often motivated not by their individual fear but because of their concern over their families and whānau. But obviously responses to a cancer diagnosis varies and the best doctors and haematologists combine giving honest information and listening to their patients.

David’s haemotologist who is brilliant says she asks, if time is shorter than you would like, what do you want to do? She says that some patients want to keep pushing for further treatment, others want to achieve a small milestone, while still more are just really sick of chemo and want to face a gentle end of life.

So responses are very variable but tied too to our general refusal to accept, or talk about, mortality in general. Most people want to live out their allotted time I guess.

Why did you have to make this film (in other words, do you think we’re bad at talking about this topic)?

I remember when saying the word ‘cancer’ out loud was frowned upon, because it was regarded as such a death sentence, and no one knew how to talk about it. I think to some degree that is still true, and one of David’s admirable qualities is a kind of forthrightness combined with a sensitivity.

Partly it might be his personality but also his experience, but he doesn’t tiptoe around topics feeling awkward which many of us do. I think his approach is a great relief to people with cancer.

During production, what was the biggest hurdle you had to overcome?

Thanks to Prime and NZ on Air, we received funding relatively easily. But like lots of filmmakers and of course all of us one way or another, COVID has meant some ducking and diving.

I was following David to Boston filming his two year (and last) tests in early 2020 and a number of the doctors we were dealing with had trials running in China, so they were looking pretty peaky. The news got worse, our planes started to be cancelled, so we hot-footed it back to Aotearoa.

The yo-yoing hasn’t been easy but you learn to be adaptable. We were able to film around the motu in the period prior to Delta so that worked for the film, and I even managed to follow one of our characters Mile to Melbourne where he had CAR T-cell treatment during the short-lived trans-Tasman bubble.

We managed just to get through the edit before this last lockdown started and were rolling into the post finishing process. That has been slowed but Department of Post and I have gotten great at digital exchanges and luckily the tools are pretty good now.

Like many documentaries, especially observational ones, this film had quite a long timeline as it does follow the trajectory of both the disease and the trials, neither of which are going to conform to a shooting schedule.

For you, what was the most memorable part of this whole experience?

I think recognising the brilliance, hard work and decency of many in the health care sector. I do think the rise of ‘anti-expert’ attitudes has tended to throw many under the bus but in the end, our success in combating COVID has been due to our politicians listening to our experts and health providers. And thank god they have.

The other striking lesson was how important family can be, and I really feel for those that face the illness more or less on their own.

What was the last great film you saw?

As a shout out to films from Aotearoa, I thought The Justice of Bunny King was great.