We hear from the directors of fulldome planetarium film Path 99

NZIFF hits a Wellington planetarium with a uniquely immersive film experience.

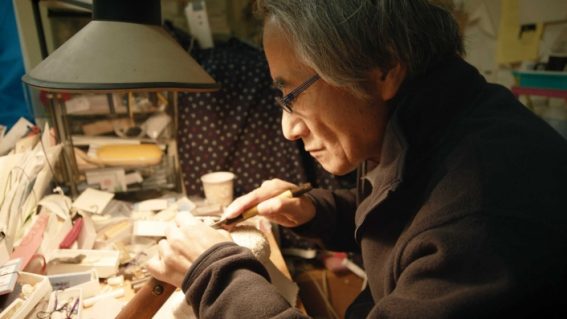

The directors of planetarium dome film Path 99 tell us about their ambitious artistic/scientific project.

Directors Dugal McKinnon and Grayson Cooke have concocted an immersive fulldome planetarium show—capturing a continent’s weather systems—with Path 99. We find out more about the film, playing at Wellington’s Carter Observatory (sold out, unfortunately) as part of Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival.

FLICKS: Describe your film in EXACTLY eight words.

McKINNON & COOKE: An immersive experience of art, science and Earth.

Is this your first experience making a dome-projected film – and what drew you to it?

McKINNON & COOKE: Yes, this is our first dome film. We have worked together for many years often on multi-screen installation projects, so it seemed like a natural progression to try our hands at filmmaking for the dome. About 10 years ago Grayson took part in a fulldome filmmaking residency in Australia, and so when Dugal mentioned the idea of working with the Carter Observatory and Space Place to produce a work for their planetarium, it turned out we had the basic knowledge and contacts to give it a go. And anyway, as media artists we are always interested in immersion. So much great art plays with immersing audiences in images and sounds, and planetariums are really rich environments designed for this experience.

What are some of the technical and creative challenges of the format?

McKINNON & COOKE: There are many challenges in making work for planetarium domes! On the visual side, firstly it’s simply the weirdness of producing circular images that ultimately get extruded onto a dome and flipped up above your head. Then you have to remember that no audience member will experience the project in the same way, because it changes depending on where you sit, what part of the dome you face, and the angle at which you face it. And finally, domes have this issue called “cross bounce”, where light hitting one side of the dome reflects to the opposite side, which requires careful handling of the image.

And in terms of sound, circular spaces make sound bounce around in interesting ways, which is definitely something to work with, by harnessing those reflections to add to the sonic texture, or by enveloping the audience. Either way, immersion!

Having flown through the cosmos at an HDU/Dimmer gig at the Stardome before, I know the power of music in that setting. How did the soundtrack come together?

McKINNON & COOKE: Making music for an expansive cloudscape has been intoxicating. The imagery can be taken in so many directions, so there was a lot of musical sketching until particular materials just settled themselves in with the image. Form was a big deal though, the challenge being to clarify structure and create motion, while at the same time maintaining the drift and shape-shifting that clouds require. Working almost exclusively with modular synthesis was a fantastic way to achieve this–there’s something about this technology which was attuned to the imagery from the very start.

Besides the spectacle of this immersive experience, what else do you hope to achieve with Path 99?

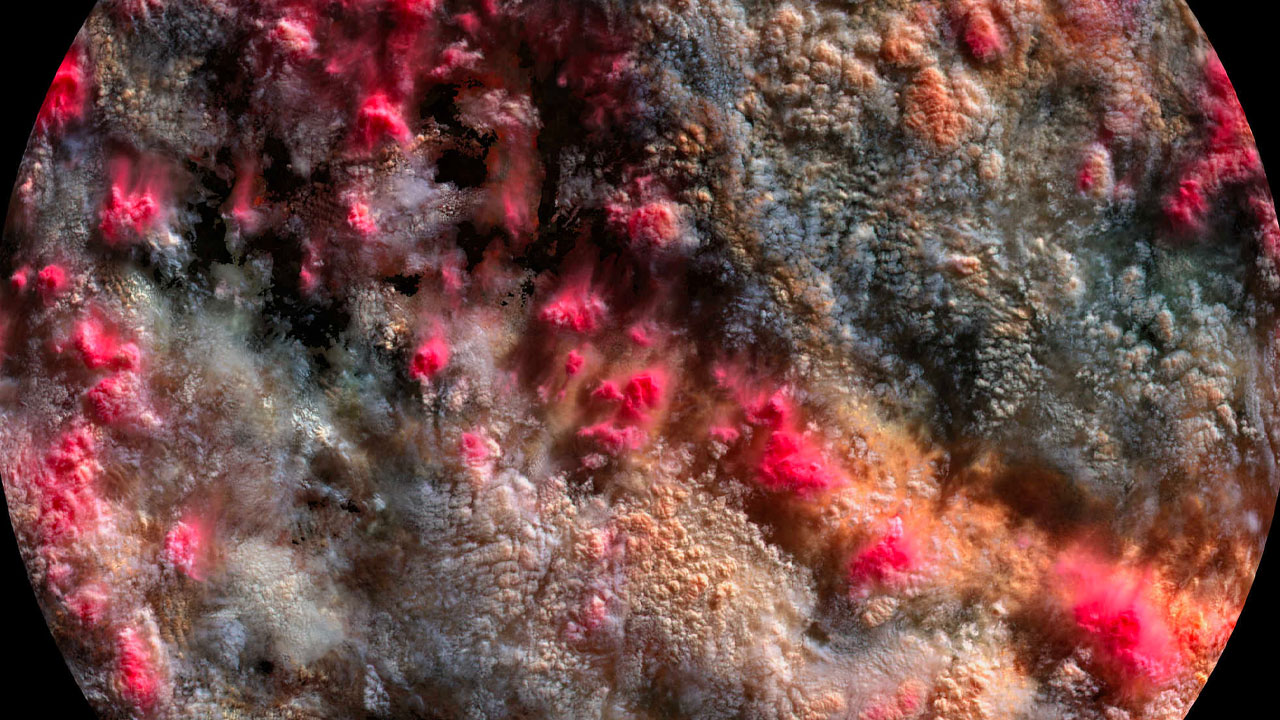

McKINNON & COOKE: Well obviously, the project is about clouds–clouds as central players in climate, and clouds simply as objects of beauty and wonder. Giving people the chance to lie back and stare up at clouds being viewed from above by satellites, is a key aim. There is this thing called the “overview effect” that astronauts report experiencing, when they find themselves outside the atmosphere looking back at the Earth as this fragile jewel floating in the blackness of space. If we can give people an experience akin to that, with the consciousness of the Earth as a kind of Gaian whole, we’ll be happy.

During production, what was the biggest hurdle you had to overcome?

COOKE: There were many! This is a complex project, involving the extraction and processing of enormous data-sets of satellite images. The biggest hurdle was probably just beginning! As in, making that decision to step off into a process I knew would require hundreds of hours of both creative fun and mind-numbing repetitive data processing. Lockdown in 2020 helped a lot–I had nowhere else to go, may as well process thousands of multi-spectral satellite images…

McKINNON: Almost 45 minutes of continuous music made for a complex production process, as well as a wonderful creative challenge, so fastidiously organising materials, mixes, and synth patches was key.

For you, what was the most memorable part of this whole experience?

COOKE: For me I think it was discovering how to work with data from the Himawari satellite. Once I figured out how to access and process it, and created the first moving images, it was just an absolute revelation, that I could create these ultra-high-resolution images showing the transport of water vapour around the planet, from a vantage point 35,786km into space. That was definitely my own “overview effect” moment.

McKINNON: Leaning into duration has been hugely satisfying, and having the creative liberty to unfold materials and textures gradually has been a slow-motion revelation for me.

What was the last great film you saw?

COOKE: The craziest film I’ve seen recently was actually Tickled, the doco about ‘competitive tickling’ by NZ journalist David Farrier. One of those films here you spend most of the time just going “OMFG!”

McKINNON: The Vast of Night. Mesmerising tracking shots, eerie B-movie aesthetics, and exquisite sound design. The best “there’s something out there” film I can recall seeing