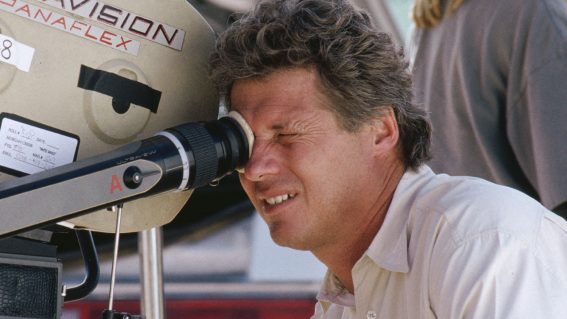

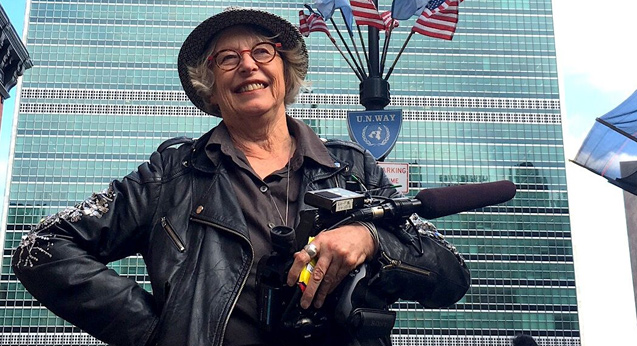

Gaylene Preston’s advice to women working in film: “go and get a gang”

The Kiwi film icon shares her experiences in the film industry.

When Gaylene Preston’s My Year with Helen was released mid-way through last year it found itself at the centre of both widespread acclaim and passionate discussion, as audiences – in particular, female audiences – ruminated on the all too familiar story of a competent, qualified and, by all accounts, exceptional woman, overlooked in favour of an apparently ‘safer male’ choice.

When, just four months after Preston’s film first debuted in June of last year at the Sydney Film Festival, the Harvey Weinstein allegations broke and the Me Too movement began, these conversations exploded as issues of women’s labour, value and discrimination finally found themselves in the mainstream.

Working in the film industry, both locally and internationally for over 30 years, none of this is new to Preston. What is, she says is the way in which we are talking about it.

As Flicks celebrates 40 years of New Zealand film, Katie Parker decided to catch up with Gaylene for a chat about boys’ clubs, the Me Too movement, and why it is still so hard for women to tell their stories.

FLICKS: Since ‘My Year with Helen’ was released, the conversation about the value of women’s labour and systematic inequality in Hollywood has expanded to become a pretty huge conversation – as a woman and a filmmaker, how has the Me Too movement resonated with you?

GAYLENE PRESTON: You’d have to be blind deaf and dumb not to have been following it, wouldn’t you? Of course, problems in the workplace of this nature are not at all new. I think what’s new is that the conversation has hit the mainstream – obviously, it’s not just the film industry that has problems of sexual innuendo.

What we’ve really had driven home over the last few months is just how easily gendered abuse can shape an industry. Have you seen that in your own career?

Oh yeah. I mean you can’t separate ‘the world’ from the world you work in.

It’s interesting because it is all about power, and if you look at what has emerged around Harvey, it’s a portrait of that. Because any woman in his orbit who had their own particular power, he wasn’t hitting on them. Any women perceived with any kind of power he didn’t hit on them, he went for people who he could dominate. And that is symptomatic of how it works in the workplace, in the home, for women. You know, how’s it going for you?

I’ve definitely felt that. I think for a lot of women it’s all really familiar no matter what industry you work in.

I just think whatever you do as a woman is not taken as seriously. There’s always room for one woman to be taken seriously, but there’s never really two, and so hopefully that’ll change.

The real problem that hasn’t had enough discussion emerging out of all this, is about storytelling and filmmaking across the board. Because it’s become a discussion about how many women have got behind cameras, you know, there’s data. This is all good, it’s all progress as far as I’m concerned. I’ve been part of the 8% since I made my first feature in 1984. That was Mr Wrong. That year it was considered that 8% of the feature films that saw a cinema in the world were directed by women. Right? It’s still 8% really.

The interesting thing is, to me, it’s not just about how many women get behind cameras, how many women get to direct for this studio, how many women get to direct television drama, although all of that is important.

What it comes down to though, is there’s a terrifying statistic that has just surfaced from a friend of mine in Sydney. Her name is Deb Verhoeven. She is an academic with a particular interest in gender in the film industry, and how it impacts storytelling. And she’s been collecting big data, that means she and another woman have collected two years worth of data on the film industry globally, and they have looked at the number of women’s films that actually get into cinemas outside their home territory, so we’re looking at global cinema. And to qualify, the film has to be made by a single woman director and it has to have had a cinema release outside its own country of 20 days. So they’ve set the bar pretty low with the 20 days, right? That’s a very short season.

Do you know what the percentage of that is? 2%. That means that even when women are making their films, and they maybe are getting them out there in their home territory, they’re not getting distributed.

Now, most women’s work is independent work. You know, I’m an independent filmmaker, I’m not delivering to a studio, and I’m not working for a television network. I’m working independently. Most women’s work is like that, in the world. The thing that hasn’t been discussed is that it doesn’t get to the audience. Why? Because the distribution industry is so sexist and so male-dominated. And while Harvey Weinstein is called a producer, he isn’t, he’s a distributor.

The distribution industry worldwide is a real problem. Audiences get built, they kind of get shaped by the product that’s there. So that’s where the problem lies.

The really sad thing to me is that I think global imagination, you know human imagination, has been severely impacted by a screen industry – film and television – that is sexist and racist and has been for a long time, and has been getting more that way over the time that I’ve been alive.

So now it appears that we’re getting more diversity and it appears like we’re getting more range in the stories that can be told, but not necessarily in our cinemas. I don’t know, what do you think?

I think that’s really interesting, and I think you’re probably really right that it all goes up to the top. For the consumer, you don’t see the stuff that doesn’t make its way to you, so don’t even know that it exists.

If you exclude local work, and you go to the cinema, how many films do you see directed by women?

Hardly any. Very few.

You know, even with all this discussion going on, we’ll have to wait and see, won’t we?

How have you felt the impact of that system locally?

If you’ve got an industry that is not conscious of its own sexism, of the whole global distribution system, then what that means is that it’s not inclusive. So it excludes the foreign. So foreign films and films from somewhere else where people might have different accents and all that, that gets excluded from the mainstream.

I mean, how all this has affected me, in my filmmaking life is that I’ve chosen to stay home. You know, because I would go away and have meetings in Hollywood and all the rest, and just feel like I did when I was allowed in my brother’s bedroom and he and his mates were playing monopoly. And I could watch but I couldn’t play. They had jokes going that I couldn’t join in on. There was a club, and I wasn’t in it.

I remember going to the Toronto film festival with Ruby and Rata, so we’re talking 1991, around about then. And that was my second feature film, and my dream at that time was to have Ruby and Rata picked up by Miramax. I would have just died, it just would have been so fabulous, right? So I was keeping my eye out for the Miramax people because Ruby and Rata did very well at the Toronto film festival. So I was whizzing round that festival talking to distributors, Miramax being my main target. And when I got to the meeting – I had a meeting with three guys in suits and a woman – and they were all wearing black, and they were all wearing this big badge that had white writing on it, white bold writing on it. And it said, “eat, fuck, kill”. And I thought “they’re not going to buy Ruby and Rata.”

Oh God. What were they like in the meeting?

They’re a gang. They’ve got their in-jokes, they’re a gang, they’re on the prowl.

That’s the problem: if you’re a woman in a male industry, you’re less likely to have a gang than the guys. The guys are having a great old time, they’re not bastards, they’re just a gang. And you’re not in it.

But on the other hand, having talked about all this, I’m one of the lucky ones, because, by staying home and staying clear of all that stuff, I’ve been able to paddle my own canoe. The deal I’ve made is to make my films cheap, but I have had first say, final cut, love em’ or hate em’, they are mine. So I mean, I don’t think I’m the sort of person who would be particularly well suited for the Hollywood system.

You say that by staying home you’ve managed to avoid a lot of those more macho dynamics. As someone who’s had a pretty active role in the infrastructure here – chairing the Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Film Innovation Fund, NZonAir, the New Zealand arts fund – have you seen less of that in the New Zealand film industry overall?

I think it’s a bit like, Trump is busy separating children from their parents at the Mexican border, and our Prime Minister is having a baby. I’m not saying that there aren’t a whole lot of macho attitudes and all the rest in New Zealand, but as far as the film industry…

When I was on the Film Commission, in 1979 I think, I was an alternate member and I was the only woman in the room most of the time, very rarely not, and it was easy to feel that I would speak up and not be heard. But I actually think that’s true when you are on boards anyway. It wasn’t because I wasn’t held in high regard. A board meeting is a discussion and I never felt like I was silenced or anything like that, in fact – because I was the only woman in the room – I probably had more to say. Because I kind of felt that I had to represent the other filmmakers like me.

As far as being discriminated against, I’m discriminated against in all the usual ways that you are too. And I myself haven’t suffered any sexual harassment in the New Zealand film industry – apart from being chased around a bedroom set by the odd Australian cameraman who would turn up when I was out directing commercials. And there’s no doubt that on some of those early film sets, you’d kind of come home, have a bath and want to actually rinse your brain out because the language was so extreme, really. And I know that while we’ve been fighting for women gaffers, fighting for women to be grips and all the rest, the girly pictures in the lighting truck can be quite demeaning.

Totally, super unwelcoming.

In the end, if someone stands on my set and says, loudly so I can hear, “who do I have to fuck to get off this movie”, I sack him. Why? Because I’m the boss.

The Me Too movement has obviously had such a huge impact on Hollywood, but as of yet it’s still kind of passed New Zealand by – do you think that we will see changes in the industry locally?

I know there are new rules of engagement being drawn up, but we’ve always had those. Every producer will be well aware of them.

I think that what is happening now is when women, or men for that matter, bring up being hassled at work, bullied, generally made to feel undignified or disrespected – because that’s what it comes down to, you don’t go to work to be yelled at – now any complaints will be taken more seriously, and perhaps people will be more likely to come forward. But I don’t think that kind of thing is ever done lightly, because it’s pretty demanding to take on your employer in the workplace.

What advice do you have for women working in local film today? Do you see the industry improving for them?

Have a good support system around you, go and get a gang. It doesn’t have to be an all-female gang, but have a gang. Because while women are busy doing kind of task-based, merit-based assessments of the world, and trying to achieve that way, the guys are all doing it on a peer group basis. And that goes from anything you like to think about, from Parliament, right through to anything. It’s peer-based approval, and peer-based entry points. So take your gang with you. Film is good like that, and I think there are a lot more young women, there’s actually a blossoming of talent, coming through now.

You know it’s taken longer than I might have thought in 1985 when I was at the Cannes film festival with Mr Wrong, but it’s happening now.

This story is part of our month-long celebration of 40 years of NZ film. Follow all our daily coverage here