Hang on, Neil deGrasse Tyson did a commentary track for The Quiet Earth?

Read some highlights from the renowned astrophysicist’s commentary track on the NZ classic he calls “one of my favourite films”.

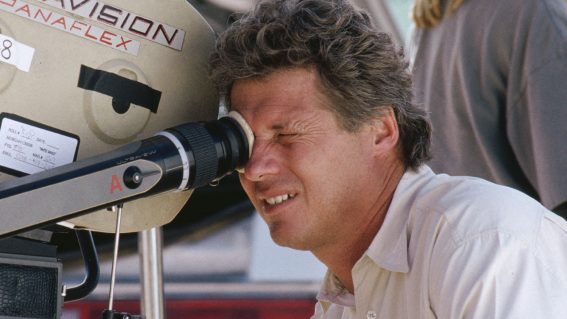

Neil deGrasse Tyson is many things – renowned astrophysicist, heir to Carl Sagan as presenter of Cosmos, guy with a great laugh – and also, as some may already know, a fan of Geoff Murphy’s 1985 Kiwi sci-fi classic The Quiet Earth. Not just a fan, but keen enough to have recorded an audio commentary track on a 2016 Blu-ray restoration and reissue of the film by U.S label Film Movement.

“I enjoyed this movie even more seeing it 30 years later,” Tyson says in his commentary as the film ends. “Movies don’t always hold up for whatever reason, either socially – that is interpersonally among characters – or cinematically. But this one, I think, it’s a story of survival, and loneliness, and technology, spirituality, love, trust, and it worked for me even more this second time around. It’s one of my favourite films, although I assume the press misrepresent that sentence as, “I think it’s one of the greatest films ever.” It’s not what I said. I can assess what is a great film and whether or not it’s one of my personal favourites. All I can say is this is one of my personal favourites from front to back, and I think they did a brilliant job.”

As this edition isn’t available at retail in NZ, here are a few other gems from Tyson’s commentary track.

It only takes 17 seconds for Tyson to begin analysing – and complimenting – the film’s science:

“When I first saw this film and I see the sun rise, I notice that the sun is rising up and to the left. That can only happen in the southern hemisphere. Or northern hemisphere people when they fake it, they film a sunset, because that’s when movie people are awake, and reverse the film thinking they’ll trick you into seeing a sunrise. They’re not tricking me. So this is either northern people reversing a sunset, or it’s southern hemisphere people actually filming a sunrise.”

“And in particular, the sunrise, up and to the left, enables the credits to first start out centred and then work their way to the right of the sun as it leaves room on the right-hand side of the screen. I thought that was brilliant. I don’t know if anyone else is noticing that, but to film a sunrise and not track the sun with the camera, let the sun slide up and to the left, and the frame is astronomically brilliant.”

Tyson displays an innate understanding of a musical instrument plus inclement weather cinema trope:

“You must know that if you’re going to be in the rain at night, and you’re going to be playing a musical instrument, there is only one instrument that should be, and it’s a saxophone, just as Zac is doing. Those are the basic ingredients for the blues. You’re not playing a violin. You’re not playing an accordion. You’re not playing the drums. You’re playing the sax.”

He subjects everything to analysis, even the humble nightie sported by Lawrence:

“I thought this scene was odd. Not that he took interest in putting on a woman’s slip, but that the woman’s slip actually fit him. It would have– he has to be a small man, and that had to have been a large woman for it to sit on his body that way. I don’t know. That just all crossed my mind. And once again, we are trying to imagine ourselves in his place, where no one is looking, and so you get to do things that maybe have crossed your mind, but societal forces and cultural/social mores prevented you from exhibiting. So we’re with him the whole time.”

You’re on dangerous ground here, Tyson, not immediately picking this film location as Eden Park and then potentially confusing us with our trans-Tasman foe:

“I don’t know if I would have recognised this field were it not for a month that I spent with family in Australia in the summer of 2015. Of course, that would have been Australia’s winter, but we saw Aussie football on this huge field. This field seemed like miles across. I don’t know if this is an Aussie football field or a rugby field, but it’s way bigger than any field any of us in America play on.”

BUSTED! A reader points out this is Hamilton’s Rugby Park. Turns out we are only as smart as Neil deGrasse Tyson after all.

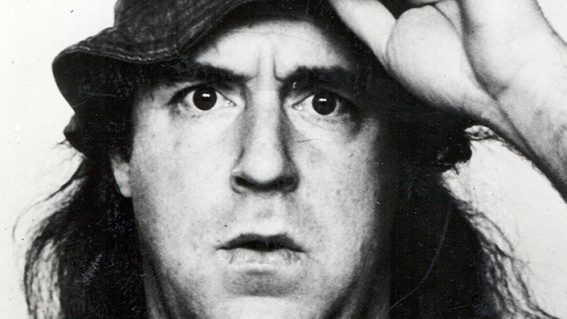

As you’d expect, there are frequent compliments about Bruno Lawrence’s character doing, y’know, science stuff:

“And there he is, once again, now in front of a wall of electronics that he’s never seen before, but he knows what knobs to turn, and what switches to flick, what screens to control. I’m loving every minute of it.”

“This may be the only film in the history of the world to show someone reaching for and retrieving physics books off the shelf. Just let the record show.”

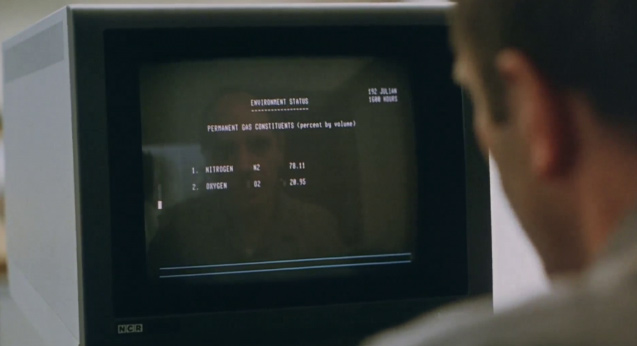

“This is a brilliant revelation of Zac that not only is the charge on the electron changing, it is oscillating, and the oscillations are getting bigger. So when you combine these effects, it is a devastating scientific conclusion that not only are things changing in the universe, they’re changing in an unstable way. You can imagine a universe where the constants of nature just shift to another value, and then that’s just a different universe. But if they’re shifting and the amplitude of that shift is getting greater, then you have a changing and unstable universe. And for me, that’s the most devastating conclusion arrived at in this movie. And that means, no, this is not just a new world that we can pitch a tent in, this world is going away as we know it.”

Tyson gets “delightfully” creeped out:

“It’s always been a little creepy to me, I mean delightfully creepy, that the third character, Api, the Polynesian native, Polynesian descendant fellow, that he has a creepy resemblance to me. And if you don’t know what I look like, just Google my name, Neil deGrasse Tyson, out there.”

Tyson did the math on this film:

“You can’t help but wonder how many people die simultaneously in the world. So it turns out there are good numbers on this or accurate numbers. We’ve got about 6,000 people per hour dying worldwide, and that divides to what now? To 100 per minute. 6,000 people per hour divided by 60 minutes per hour, you get 100 people per minute. So that’s a little more than one per second worldwide. Well, I don’t know how long the effect is supposed to have lasted, but if you measure it in the film, it’s about five seconds. About five seconds. So five seconds would give you eight dead people in the world.”

“Clearly, none of those eight dead people would be in Hamilton, New Zealand. Okay? They’d all be somewhere else, you know, in China, wherever, someplace where a lot of people live. So, you’ve got to loosen up the numbers on this in order to have three people die simultaneously in the same city. Now back in 1985 when this film was produced, the population of the world was just under five billion, and the population of the town might have been around 150,000.”

“So, in that town, one person dies every five hours about, plus or minus. So in order to get three people, the effect would’ve had to have lasted 15 hours. And so there you have it. That’s just if you run the numbers. But, once again, we let it go because the story is trying to take you somewhere else, and there are other messages that matter more than getting any of that arithmetic correct.”

He may know about many, many things, but Tyson also understands the power of leather:

“So Joanne has this challenge, of course, this love triangle. You know, does she want the guy who knows science and could possibly rebuild civilisation? And he’s a little bit geeky but not as geeky as they could have made him. Or does she want the virile guy who’s also spiritual?”

“You know, maybe in the days of cavemen, the woman would select the man who would keep her warm and dry and safe. And that would clearly be Api. But in modern times, does she want the scientist engineer who will, in fact, be able to use civilisation, the fruits of civilisation to stay alive? So I enjoyed this dynamic, this choice that Joanne was given. And she acted this brilliantly just to show that she harboured no resentment against either of them, but in the end, her primal urges lean towards the guy who is physically fit, spiritually motivated, and wears leather pants.”

Tyson’s fascination with the film’s love triangle begs the question – has the astrophysicist ever competed for someone’s affection against a fit, leather-clad dude? He seems remarkably well-informed about the dynamics…

“I liked this scene because I can feel for the scientist who is looking at the woman who he’s clearly interested in, but notices without doubt that she’s really interested in Api. And there’s Api again with his leather clothing, and he’s physically fit, and he’s got an earring, and he’s all spiritual. And so the frustration of not getting the woman you want because she wants somebody else, it’s there. But all he can be is himself. He’s a scientist tech-head, but he’s mature enough to accept that fact. So I thought this was brilliantly captured, essentially without words.”

Time for some sexy science:

“If you’re going to repopulate the Earth with two humans, what you want is the greatest genetic diversity you could come up with so that your offspring have the best chance of surviving variations in the world. This is what natural selection is, and that’s what it does. So here we have someone clearly Northern European, very pale-skinned, red-headed, likely Irish in her ancestry, and then we have Api who is of Polynesian descent, and that’s the greatest genetic diversity pair you’re going to get out of the combination of the three of them. So I thought this was an interesting moment there, this Adam-and-Eve moment.”

“If there’s going to be a world, they’re the ones who are going to take it over [laughs like only Tyson can]. And without the science [meaning Lawrence’s character], I don’t know how far they’d get, but maybe you don’t need the science if there’s no place to apply the science. Clearly, prehistoric humans had no science at all, and they got along for tens of thousands of years without it.”

So, what about THAT ENDING, Neil?

“My favourite planet is Saturn. I don’t know if you have a favourite planet. I have a favourite planet. It’s Saturn, and it is rising. It is rising beautifully in that backdrop. And this is before meaningful CGI was helping the movie makers. So they probably did this physically with physical artwork, but it’s gorgeous, and I’d want my bedroom window to have that scene every morning. By the way, in the 1980s, we had better and better images from the Voyager spacecraft of planet Saturn, far exceeding anything our ground-based telescopes were giving us. So that image of Saturn was completely inspired by the newly available Voyager spacecraft images that NASA had been obtaining.”

This story is part of our month-long celebration of 40 years of NZ film. Follow all our daily coverage here.

You can watch ‘The Quiet Earth’ on demand, buy the DVD (with commentary by writer/producer Sam Pillsbury), but if you want to listen to the Neil deGrasse Tyson commentary you’ll probably need to do what we did and order it on Amazon.