I’ll Be Gone in the Dark is a uniquely personal true-crime triumph

A six-part true-crime series comes to Neon, based on the best-seller of the same name.

A six-part true-crime series comes to Neon on June 29, based on the best-seller of the same name, and telling the story of the author’s search for a prolific serial offender. As Steve Newall observes, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark finds new emotional depth in a familiar genre, telling more than just the awfully compelling story of vile crimes.

Content warning – I’ll Be Gone in the Dark (and this piece) discuss violent sexual assault and murder.

One of the early stars of the online true-crime era, Michelle McNamara spent the early 2000s chronicling crimes on her website TrueCrimeDiary. Obsessing over the details and conveying them in expressive prose until the early hours of the morning, often while husband Patton Oswalt and, later, her daughter slept, McNamara became increasingly captivated by a serial rapist and murderer she helped to name as the Golden State Killer.

See also

* All new movies & series on Neon

* Everything coming to Neon in June

Previously known by the acronym EARONS (East Area Rapist/Original Night Stalker), he was responsible for more than 50 rapes and at least 13 murders from the mid-70s to mid-80s. One was similar to the next, even as they became more brazen and built to the realisation of cruelly violent impulses. EARONS staked out his victims ahead of time, knew their movements in detail, took similar precautions to evade identification—and made similar threats to survivors. “Make one move and you’ll be silent forever and I’ll be gone in the dark,” he told one woman at knifepoint, a threat McNamara repurposed as a book title.

McNamara’s initial interest in the case snowballed over the years, as recounted in her book I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer (a read I can’t recommend enough). Forming relationships online and in person with other amateur sleuths, law enforcement professionals, and the serial offender’s victims, McNamara was doing more than simply recounting history. She wanted people to know about a series of crimes staggering in scale and personal impact and then, increasingly, McNamara became obsessed with solving them.

The book promised so much, looking set to introduce readers the world over to a unique voice in the true-crime genre. Tragically, McNamara died unexpectedly, leaving her captivating work to be published posthumously. As the gripping new show I’ll Be Gone in the Dark recounts, one that’s adapted from her book and life, what McNamara brought by way of intensity, dedication and obsession to the case played no small part in her death, as she became another of the headlines associated with EARONS, even if not by his hand.

Now this show delves even deeper into the personal dimension of her story, exploring the work and life of an author who, as we hear here, her publisher considered as the strongest writer in true-crime since Truman Capote, thanks to her ability to conjure emotion and experience in the mind of the reader, and her embrace of the personal in her writing

I’ll Be Gone in the Dark sets out ambitiously with various objectives over its six episodes. On the traditional front, there is a multitude of crimes to chronicle, a history to trace and a mystery to chase. And in keeping with the spirit of McNamara’s writing, the series takes pains to allow the Golden State Killer’s survivors to share their experiences, telling their stories rather than merely recounting a horrifyingly long list of atrocity and torment.

As well as first-hand accounts of their trauma, we also hear the long term impacts of their experiences. It’s a diverse group of voices that emerges, one that forms a unique community as the series progresses, particularly explored on-screen in the final episode.

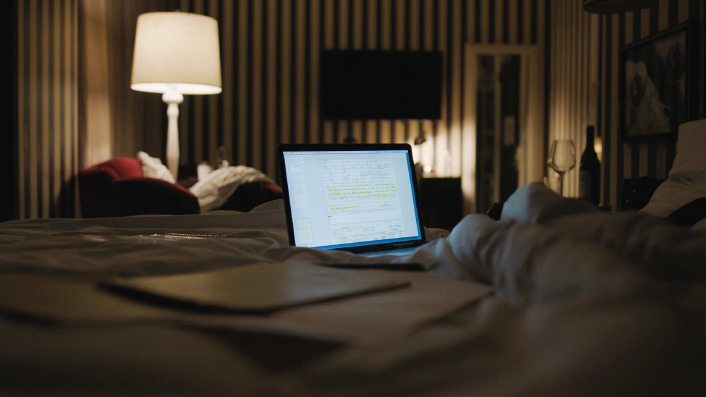

There’s also McNamara’s own role in the investigation, of course, one that brings the series into contact with message board obsessives, “citizen detectives” who pore over every detail of the case, exchanging clues and trading clues and access to information in a way that at times comes across like a particularly unhealthy community of baseball card or war memorabilia collectors.

They know the victims and locations in detail, and through them I’ll Be Gone in the Dark visits the suburban locations of EARONS’ acts of sadism, ordinary middle-class cul de sacs that, if you squinted, could easily be mistaken for family-friendly streets in Aotearoa.

Through the survivors’ accounts, interviews with the police who pursued EARONS, and archive news and current affairs footage of the time, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark is also a grim account of rape in the mid 70s to early 80s. As the community panicked, investing vainly in home security, neighbourhood patrols and firearms, victim blaming was rife, and as we see here, “instructional” videos reiterated the view of the time that women’s behaviour actively encouraged their own assault. Troubling insights into police practices are also documented here, from revictimisation of survivors to grueling listens as hypnotic techniques are committed to audio, and even a panel of convicted rapists sharing their “insights”.

It’s also truly shocking at one point to hear just how many serial rapists were active in the same region at the same time—an era in which technology and law enforcement techniques were incredibly lacking, until entering the time of DNA analysis—at which point EARONS effectively vanished. Did he know his time was up?

Of course, the most traditional element of true-crime is also present, with the Golden State Killer’s actions recounted in detail. The show traces the escalation of his offending, and the repetitive M.O. Like McNamara and her fellow investigative enthusiasts, it’s tempting to speculate as to what sort of person he might be, based on the details of his acts, to theorise about what compelled him to break into homes and terrorise the occupants.

I’ll Be Gone in the Dark eschews crime reenactments (a device critiqued elsewhere in the show as reveling in the torment of actresses in lingerie), but establishes an effectively creepy visual shorthand as it recounts individual attacks—each time the show’s visual device of shadows rapidly lengthening, like talons reaching for a victim, begins, a sense of creeping dread grows, channeling the eerieness of McNamara’s scene-setting writing.

As well as her role as chronicler and investigator, the show also finds time to treat McNamara as a subject in the same way she engaged with others. You’re quite likely to end up asking yourself what made her gravitate to true-crime, and to obsess over this case to such a degree. I’ll Be Gone in the Dark explores McNamara’s history, proximity to murder, and the complications she experienced navigating her own upbringing, adding further texture to a show already heavy in personal experiences.

A relentless documenter, McNamara’s trove of audio and video audio recordings, as well as access to personal materials fill the six episodes. Her present-day absence is keenly-felt, though, with the series building to a reveal of her own story as it traces the search for EARONS. Through it all is her husband Patton Oswalt, recounting their relationship, sharing his perspective on her work, helping to tell her story, and tragically sharing the circumstances of her demise.

As the series winds its way closer to the present, particularly after its depiction of McNamara’s book being published, we’re offered an up close view as to how this case and the people involved still provide him some connection to his deceased wife, this awful case and the horrific crimes perpetrated by a vile human being having established bonds that defy the perpetrator’s inhumanity and defy his destructive acts.