A manipulative misogynist’s cult is explored in docuseries The Vow

Behind the shocking headlines lies manipulation, shame and remorse.

Investigative docuseries The Vow comes to Neon from October 21 and explores alleged self-improvement organisation NXIVM, not a typo but actually a cult, one that would go on to make headlines worldwide. Amanda Jane Robinson looks at how The Vow explores the shame and remorse of former members as it outlines the cult’s history.

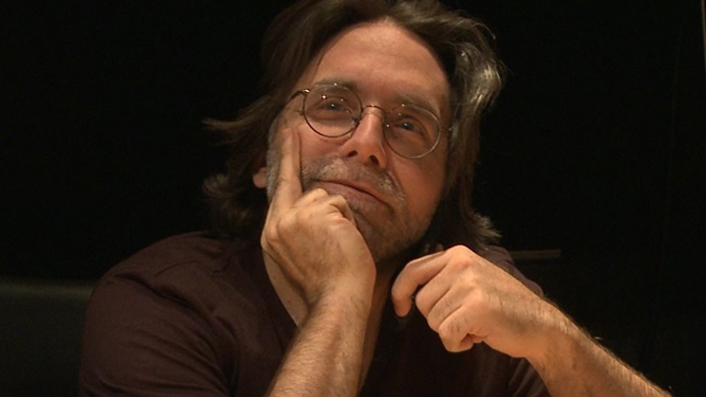

Last year, Keith Raniere was found guilty of sex trafficking, sexual exploitation of a child, possession of child pornography, identity theft, forced labour, and various counts of conspiracy and racketeering. At the end of October, he will be sentenced. Next week, HBO’s The Vow—a nine-part docuseries recounting the rise and fall of NXIVM (pronounced nex-ee-um), the self-improvement company turned sex cult Raniere founded—will premiere in New Zealand on Neon.

See also:

* New release movies & series on Neon

* Everything coming to Neon this month

In The Vow, filmmakers Karim Amer and Jehane Noujaim follow a quartet of ex-NXIVM members; Sarah Edmonson and her husband Anthony ‘Nippy’ Ames, Mark Vincente and his wife Bonnie Piesse; detailing how they individually absconded from the cult and their collective efforts to bring charges against Raniere and other high-ranking members of the organisation.

Originally billed as a self-improvement company, NXIVM’s initial offerings constituted personal and professional development through its Executive Success Program seminars, in which ‘large-group awareness training’ was used to increase attendees’ self-awareness in an effort to transform their lives. According to founder Keith Raniere, the aim of NXIVM was to “have people experience more joy in their lives”. Essentially, NXIVM was a pyramid scheme that relied on constant recruitment, using teachings from the human potential movement to prey on individuals’ insecurities, make money, and—eventually—provide Raniere with a sustained supply of women to have sex with.

NXIVM’s operations were informed by a wide variety of sources: Freudian psychoanalysis, Steiner’s anthroposophy, Rand’s objectivism, Bandler and Grinder’s neuro-linguistic programming, Ehrard seminars training, Scientology, hypnosis, motivational speaking, the United States Navy, and multi-level marketing practices.

In classes, rank was displayed through coloured sashes similar to the Judo belt system. Participants pledged to “purge” themselves “of all parasite and envy-based habits”, to enrol others, and to “ethically control as much of the money, wealth and resources of the world as possible”. Expensive intensives were run for twelve hours a day, sixteen days at a time, in which attendees would participate in modules in which they were instructed to “explore the benefits they would receive in the event of a partner’s sudden death” or “discuss psychopaths and their followers”. Once signing up to the organisation, sleep deprivation and financial exploitation soon followed.

From the outset of the show, it seems impossible that so many successful, seemingly well-adjusted people could have believed NXIVM was anything but a scam. To watch, Raniere is not particularly magnetic, asking attendees moronic questions like: “do you want to be a millionaire of joy?” and demanding that members refer to him as Vanguard. For a cult with Hollywood entanglements, the organisation was markedly unglamorous. There were never any drugs, just hideous sashes, run-down conference rooms, and compulsory all-night volleyball tournaments. Yet it continued to attract members.

As NXIVM grew, smaller groups began forming within the organisation; JNESS, a women’s leadership group; the Society of Protectors, a men’s group; and, eventually, DOS. The majority of the criminal charges filed against Raniere, and the majority of The Vow, focuses on DOS. Dominus Obsequious Sororium—which roughly translates to ‘Master over Slave Women’—was a “secret sisterhood” within NXIVM in which women were referred to as each other’s slaves and masters, subjected to calorie restrictions and corporal punishment, branded with the initials of Raniere and his associate, actress Allison Mack, and required to provide nude photos or other potentially damaging information about themselves as “collateral” to be released if they ever spoke out about DOS.

In the fourth episode of The Vow, an anonymous ex-DOS member details her relationship to her master, the requirement that she text her master asking permission for any food or drink she wanted to consume. Watching the way the women of DOS turned on each other within this framework is one of the show’s most effective and disturbing elements.

Despite the show’s well-crafted deep-dive into DOS’ horrific practices, little background is given on Raniere’s life before the cult, nor is Allison Mack’s exact role in the organisation ever clearly defined. The wealth of everyone involved—multiple participants had the Dalai Lama’s personal phone number—is never questioned, or even consciously considered.

Instead, the show’s creators anchor their series around the self-mythologising of the core group of NXIVM defectors, without ever fully interrogating their accountability. Even taking into account the profound nuances of cult brainwashing, the show’s core cast aren’t always the most sympathetic. While watching, it’s easy to get the impression that their willingness to be a part of the series is an attempt to distance themselves from the culpability for the harm they did to the thousands of people they collectively recruited to the organisation.

That’s not to say there aren’t moments of real empathy, or that the participants aren’t self-aware. The arc of NXIVM member and actress Bonnie Piesse—intuiting that something wasn’t right and having the courage to act on that instinct and leave, even when Mark Vincente, her husband and NXIVM figurehead, took Raniere’s side—is profoundly moving to witness. The psychological toll of her involvement in the cult is evident when she is retraumatised after actress Catherine Oxenberg makes a joke about how Bonnie used to sleep in a dog bed on the floor as “penance”.

In the same episode, Mark watches footage of himself shaming and humiliating workshop attendees, forcing them to plank on the floor. His regret is palpable. “What am I, fucking stupid?” Near the end of the series ex-NXIVM member Nippy Ames examines where he’s at with his emotional healing: “I’m having a hard time un-fucking my own head. I trained people to heil Hitler, how do you unring that in your own psyche?” There are many villains in this story, not least the police in their inexcusable refusal to act against Raniere for years, even when brought evidence of sexual slavery.

It isn’t until the show’s eighth episode that we see the real Keith Raniere and come to understand the point the filmmakers have been trying to make all along: Raniere doesn’t have some grand motivation for his actions, he is simply a manipulative misogynist who believes himself to be the smartest person in the room. “When a man looks at you women”, he says, “all we see is a bunch of little kids”. In a confronting scene, Raniere calls Sarah Edmonson a “cocktease” in front of a seminar crowd under the guise of communicating “what men are really thinking”, quite visibly taking pleasure in her humiliation as she begins to cry. It’s one of many tense, uncomfortable moments in the show’s run.

The Vow does not touch on the most disturbing of Raniere’s actions, that he kept an undocumented woman confined to a room for two years out of jealousy over her attraction to another man, threatening her with deportation if she left. Prosecutors have also accused Raniere of having had sexual relationships with a fifteen-year-old girl and at least one other child, and also of possessing child pornography between 2005 and 2018, which also goes unexplored here.

There’s also a tension intrinsic to the existence of the series itself—so much of the footage used in the show is cut together from a documentary Mark Vincente was making in his role as Vice President of Communications for NXIVM that was intended to rehabilitate Raniere’s image. Combined with the show’s confounding lack of timeline, this unsettling fact means that as a viewer you’re never quite sure if what you’re watching is part of the initial NXIVM propaganda or the fight against it.

Yet in all its disconcerting disarray, The Vow engrosses. The questions it raises about the intricate relationship between empowerment and manipulation feel especially resonant, as does its exploration of shame and remorse. While it may miss as well as hit, The Vow is an unnerving depiction of trust and trauma that is worth a watch if only to contextualise this month’s sentencing.