Is Volodymyr Zelensky’s Servant of the People stranger than fiction, or weirder than history?

Before he was President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky played the President in a comedy series that bizarrely pre-empted his political career.

Before he was President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky played the President in a comedy series that pre-empted his political career. Luke Buckmaster looks at the strange case of Servant of the People.

Servant of the People: Season 1

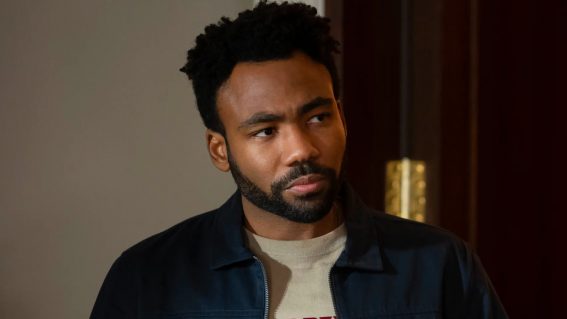

The expression “stranger than fiction” sort of applies, and sort of doesn’t, to the Ukrainian comedy series Servant of the People—which follows an average Joe high school teacher who becomes president. Running from 2015 to 2019, the show has been solidified in the history books not because of what it depicts, per se, but due to a weird glitch in the Matrix that saw its narrative pre-empt reality itself. The man who plays the president—and created and produced the series—is Volodymyr Zelensky, whose face you’ve no doubt seen recently on the news.

Zelensky really did run for President of Ukraine in 2019, and really did win, then of course became a prominent figure in global media following Russia’s invasion of the country in February. The aforementioned expression is often invoked to describe real-life stories that venture to places so incredible they would seem far-fetched in made-up narratives. But in the case of Servant of the People—a decent albeit unexceptional comedy elevated by quirks of history to the realm of the highly interesting—it is only strange because it began in fiction, summoning new kinds of noodle-scratching confusion.

Protagonist Vasily Petrovych Goloborodko (Zelensky) follows in the footsteps of many film and TV commoners who have had their salt of the earth values challenged by the grubby world of politics—frdaryom James Stewart in 1939’s Mr Smith Goes to Washington to Deborah Mailman more recently in Total Control. Like Stewart’s Boy Scouts leader-cum-senator, Goloborodko—who is entertainingly performed by Zelensky in a relatable, straitlaced style (the Darryl Kerrigan of Ukraine?)—is a wholesome character but no pushover.

The series clearly aspires to be razor-sharp satire, in the key of Francis Veber or Armando Iannucci. But the tone is more enjoyably jovial, now with an unintended tinge of pathos. Visions of life in Ukraine are cushioned by that soft, innocuous sitcom aesthetic, painting a world where nothing terribly bad ever really happens. In the bitterly funny experimental series Kevin Can F**k Himself, we saw that aesthetic countered in scenes lurching from warm lighting and a laugh track to a grim social realist veneer. With Servant of the People, a terrible juxtaposition is drawn from reality itself: the show’s pleasant world on one hand, and Ukrainian people in real-life experiencing near-unimaginable suffering on the other.

The premise launches after Goloborodko delivers to a fiery rant to colleague about the corrupt, woebegone state of Ukrainian politics, which is secretly filmed then uploaded to YouTube. The video becomes a viral sensation and the public view it as a fine audition tape for the top job—just as Ukrainians in real-life came to regard Servant of the People in the same way. Zelensky in fact relied heavily on the show to do his electioneering for him. Which is very weird: imagine if Julia Louis-Dreyfus ran for president in America, relying on voters to have seen Veep rather than outlining real-life policies.

Under the headline The World Just Witnessed the First Entirely Virtual Presidential Campaign, Politico reported that Zelensky “not only traded on the image of a complete outsider, he also did no face-to-face campaigning, made no speeches, held no rallies, eschewed travel across the country, gave no press conferences, avoided in-depth interviews with independent journalists and, until the last day of campaigning, did not debate.”

The consensus seems to be that Zelensky is doing an extraordinary job during the current conflict, particularly when it comes to public relations and the important work that entails—from addressing parliaments to calling for support from the United Nations. I have watched him in awe, observing that this balls are obviously made of steel, and on top of being inspired by his courage under fire I have learned he supports meritorious social policies too—such as medical cannabis and free abortions.

In the third episode of Servant of the People, Goloborodko is tutored by an advisor on how to deliver a good speech to the people with the correct cadence and posture—the scene (which is amusing, but like much of the show doesn’t click into a high comedic gear) weirdly culminating with him stuffing nuts into his mouth in order for his words to “flow like a song.” Zelensky himself didn’t need that kind of training, his experience as an actor preparing him—at least in terms of performative elements—for what would become the role of his life.

As if the sort-of stranger-than-fiction (but sort of not) scenario of Servant of the People wasn’t weird enough, Zelensky’s lack of presence during the run-up to the election was preempted by the show, which he appears to have used as a strategic blueprint. Despite winning the (real-life) election in a landslide, there must have been voters displeased about the frontrunner avoiding the usual scrutiny. In the show, the lack of an election campaign (Goloborodko wins without running one) feels like a gap in the writing—the protagonist going from zero to hero with nothing in between. There’s little sense of struggle, and no comedy wrought from kissing babies, wearing hardhats and dealing with cranky constituents.

Caught between reality and make believe, Zelensky probably—and correctly—thought: if it worked for my character, it can work for me.

Servant of the People: Season 1