Girl on the Third Floor isn’t a horror to renovate your Netflix queue

Noble but frustratingly uneven attempt to revitalise stale haunted house conventions.

Renovating a rundown mansion into a family home, a father-to-be finds himself in a terrifying position when the house rejects his plans.

Now streaming on Netflix, Girl on the Third Floor is a morality yarn about toxic patriarchy’s long-overdue comeuppance, writes Aaron Yap, but one that doesn’t develop a distinctive enough sensibility to lift it above Netflix library-filling adequacy.

For anyone tracking the American indie genre movie sphere over the last ten years, the name Travis Stevens will be familiar. If there’s a guy who knows his way around a low budget, it’s Stevens, the prolific producer of such fiendish micro-shockers as The Aggression Scale, Cheap Thrills and Starry Eyes. Disappointingly, his directorial debut Girl on the Third Floor is one of the more middling things he’s done. Despite some promising first steps, the film doesn’t develop a distinctive enough sensibility to lift it above Netflix library-filling adequacy.

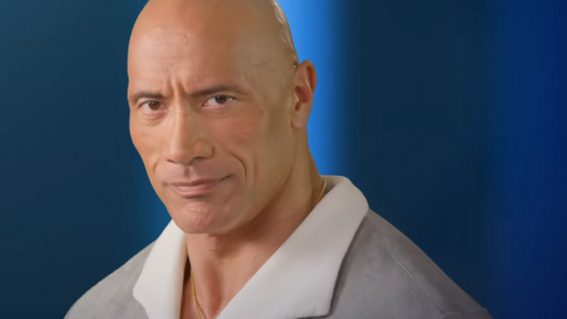

It’s a noble but frustratingly uneven attempt to revitalise stale haunted house conventions with pressing social currency. Essentially, Girl on the Third Floor is a morality yarn about toxic patriarchy’s long-overdue comeuppance, observing the downward spiral of recovering alcoholic fraudster Don Koch (former WWE wrestler Phil Brooks) as the old house he’s renovating, in the hopes of starting afresh with expectant wife Liz (Trieste Kelly Dunn), starts turning on him.

The house is unquestionably the star here. It’s dressed to the hilt, and Stevens allows ample time for the viewer to settle into its rotten, malignant spaces before unraveling its sordid history. There’s viscous liquid leaking out of electric sockets, black goo curdling behind ornate wallpaper, and terrible plumbing galore. The spectre of The Shining and Evil Dead haunts the proceedings: who is Koch but basically Jack Torrance played by Bruce Campbell, although that’s probably giving the ropey acting of Cook, who resembles a low-rent Jon Hamm, too much credit.

Girl on the Third Floor works more favourably as a jet-black farce about alpha-male home improvement gone fatally wrong, stacking a few agreeably macabre turns up its sleeve. But the writing can be embarrassingly clunky, most glaring when it labours to consider the transgressions of men through a feminist lens without the lived-in nuance and authenticity that at least one female writer might have contributed to the screenplay.