Shadow is the best action movie of the year – and you probably haven’t heard of it

If you’re in Auckland, Luke Buckmaster implores you to see this.

Is it possible that the greatest action movie of the year is now playing in cinemas, and nobody noticed? If you’re in Auckland, critic Luke Buckmaster implores film lovers to see Chinese director Zhang Yimou’s visually ravishing new production.

Have you, at any point this year, sat in a cinema and found your jaw slackening and eyes widening, hit by the sensation that you were experiencing something genuinely fresh and different?

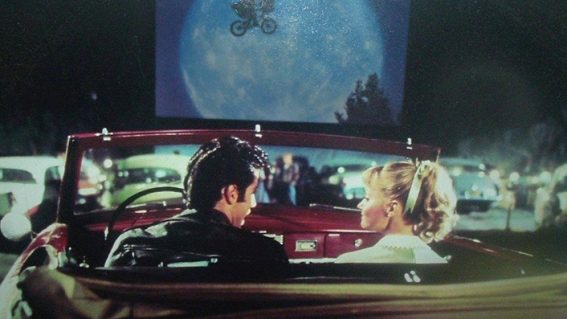

I got that feeling in March watching Terror Nullius, an experimental political film that pilfers scenes from classic movies and re-edits them (a bit of Mad Max here, a splash of Grease there) to create new incendiary meaning. I got it again in June watching The Pure Necessity, which re-animates The Jungle Book by removing the human elements (including all people and dialogue) thus creating the trippiest of nature documentaries.

And this week I sat, gobsmacked, through legendary Chinese director Zhang Yimou’s epic Shadow – a magnificent production and the best action film of the year. It makes the widely acclaimed Mission: Impossible – Fallout look pedestrian in comparison; a supermarket pot plant next to Zhang’s 1000-year-old mist-rimmed tree. You might not have heard of it, but the film is playing in cinemas right now – which is where it should be seen.

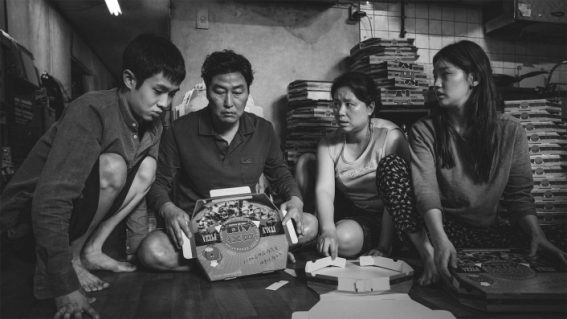

What makes Shadow so special? Many things. First and foremost the visuals. Oh, the visuals. Zhang and cinematographer Xiaoding Zhao (who shot one of the director’s most famous movies: House of Flying Daggers) filmed Shadow in colour, but filled it with black and white constructions – including all-monochrome sets and costumes. The majority of the time the only element of the mise-en-scene with colour is the actors’ skin.

This style was inspired by Chinese ink brush paintings and the tai chi diagram (otherwise known as the Yin Yang symbol) and I’ve never seen anything quite like it. Terror Nullius generated visual wow by rearranging elements; The Pure Necessity by removing elements; and Shadow by scaling elements back. Zhang intensely contemplates every single splash on the canvas: what every dab means; what every bit of colour connotes.

It’s visually ravishing from the introductory moments, but not striking in a way that has your jaw instantly hitting the floor. The complicated beauty of this film creeps up on you. At one point a character addresses a musician playing in a misty bamboo forest (every bit as picturesque as it sounds) and describes the tune he is playing as a ‘lingering melody that feels trapped, no way out.’

The colour in this film feels trapped too. Wafts of it escape, with glimpses of non-monochrome properties other than skin slowly appearing: green leaves, brown bamboo, and most notably the blood that oozes from wounds once the shit goes down. The juggling of black and white isn’t gimmicky (like Pleasantville) or extraneous (like Rumble Fish). And the ravishing, transcendent charcoal effect is enhanced by the weather in this universe: namely the fact that it is almost always raining.

I’ll return to that in a moment, because I’ve been delaying a plot synopsis as long as possible. The story is set during the ‘Three Kingdoms’ era of Chinese legend (220AD – 290AD). It revolves around a petulant King (Zheng Kai) who has trouble asserting his authority, and a noble commander (Deng Chao) who rallies against him. The King doesn’t know that the commander is actually a doppelganger, or ‘shadow’. The real commander (also Deng) is a hippy-haired Miyagi-like hermit.

The water bounces off the ground and mottles the trees. It drizzles the characters as they engage in choreographed combat, presented in a beautiful style we have come to expect from Zhang: like ancient dance routines channelling the spirit of some far-flung treetop god. Water is an easy way to intensify atmosphere, but it’s also embedded into the film’s themes. Urged to fight in a more “feminine” way, characters use a gnarly reinvention of the oil paper umbrella, which doubles as a small spinning vessel (wait until you see the sensational shot of a group of soldiers invading a village by spinning down the street).

Much of the first hour unfolds in close quarters, consumed by conversation and political maneuvering. It takes an hour or so for Zhang to deliver the awe-inspiring spectacle for which he is known (his most celebrated works include Raise the Red Lantern and Hero). Then, the audience hooked on the taste of grand confrontation, the director snatches it away again, returning to mostly interior-set corridors-of-power drama to round out the running time.

It’s a galling way to structure the narrative, guaranteeing a certain amount of audience dissatisfaction. But it also reiterates where the director’s priorities lie. While other films of a similar ilk throw magic dust on our faces, distracting the audience from moral quandaries and inconsistencies, this film is deeply interested in morality and justice – which is not the same, of course, as saying the bad guys perish and good always prevails.

With its blatant disregard for the promise of fulfilling spectacle, the third act makes a point: the deaths that mean something are the ones that involve exchanges of words and deep feelings. The presence of a corpse signifies the end of a life rather than the beginning of a new effect. Long after audiences feel disappointment from the aborting of the battle scenes, thrilling memories of this extraordinary film will remain.