Impressive and immersive, Mank is a fascinating world to spend two hours in

An Oscar nomination for Gary Oldman is all-but-guaranteed with David Fincher’s latest.

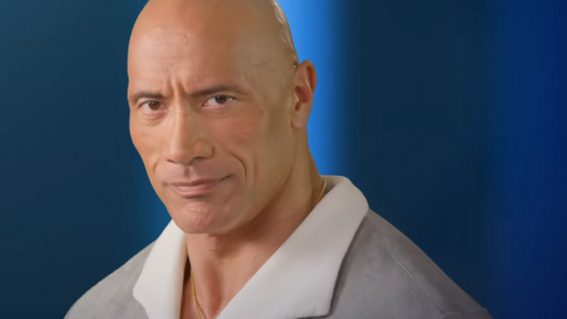

Now playing in limited release in select North Island cinemas and streaming on Netflix from December 4, David Fincher’s Mank chronicles the creation of Orson Welles’ masterpiece Citizen Kane via alcoholic screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman). The film delights in era-appropriate details, writes Matt Glasby, although those not versed in Hollywood history may struggle.

Like a multiplex Kubrick, David Fincher specialises in creating meticulously crafted cinematic worlds—but his films beat with a dark heart, if they have one at all.

Based on a script by Fincher’s father, Jack, this prestige Netflix picture tells the story of legendary screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman). We first meet him in 1939, holed up with a broken leg and a booze problem while no-nonsense secretary Rita Alexander (Lily Collins) jots down his every word. The task in hand: to write Citizen Kane for Orson Welles (Tom Burke) in just 60 days.

See also:

* All new movies & series on Netflix

* Everything coming to Netflix in December

From here the film jumps around in time, exploring behind-the-scenes Hollywood and the many controversies of Welles’ masterpiece. Kane and his second wife were based on newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and his mistress, the actor Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried). Over the years, we see Mank attending their parties, falling into the role of court jester/drunken savant when his put-upon wife, known to all as “poor Sara” (Tuppence Middleton), isn’t around to stop him.

Shot in beautiful black-and-white by Erik Messerschmidt (Mindhunter), the film delights in era-appropriate details such as back projection and cigarette burns in the corner of the frame. Fincher Sr’s dialogue whirs with the rat-a-tat of a thousand backlot typewriters, and scurrilous gossip mixes with Kane call-backs to intoxicating effect.

At the centre of it all, is Oldman’s shabby seer, a man of principle trying not to get lost in the Hollywood maelstrom. While an Oscar nomination for Oldman is all-but-guaranteed, Mank is only occasionally allowed to let his guard down. One such moment is a spectacular, alcohol-fuelled rant directed at Hearst and requiring (according to Dance) a Kubrickian 100 takes. The other is a rare show of pathos, when Mank admits to his more successful writer/director brother Joseph (All About Eve), “I’m washed up, Joe, have been for years.”

Impressive and immersive, this is a fascinating world to spend two hours in, although those not versed in Hollywood history may struggle. Also, despite much talk about the emotive power of the movies, it’s a film that only seeks to engage the brain. But perhaps for an unsentimental SOB like Mank—not to mention Fincher—that’s the whole point.